My student, a skinny Somali kid named Kaynan, arrives early this spring morning to finish up an assignment. I offer him coffee (one of the many indiscretions of a teacher’s day) because he got out of bed at 6 to get here and because he is a bit bowled over by the tenth grade, and because I think he can finish the year if he works at it.

Kaynan joined the baseball team at our small charter school this year, and looks a bit like a clown when he runs because the school’s uniform pants are way too large for him. He bounds around the field and his teammates call him Pirate. It’s nice to see him out of the shadow of the North Cambridge high rise housing project he lives in, and away from the strain of parents desperately working to escape poverty and prejudice.

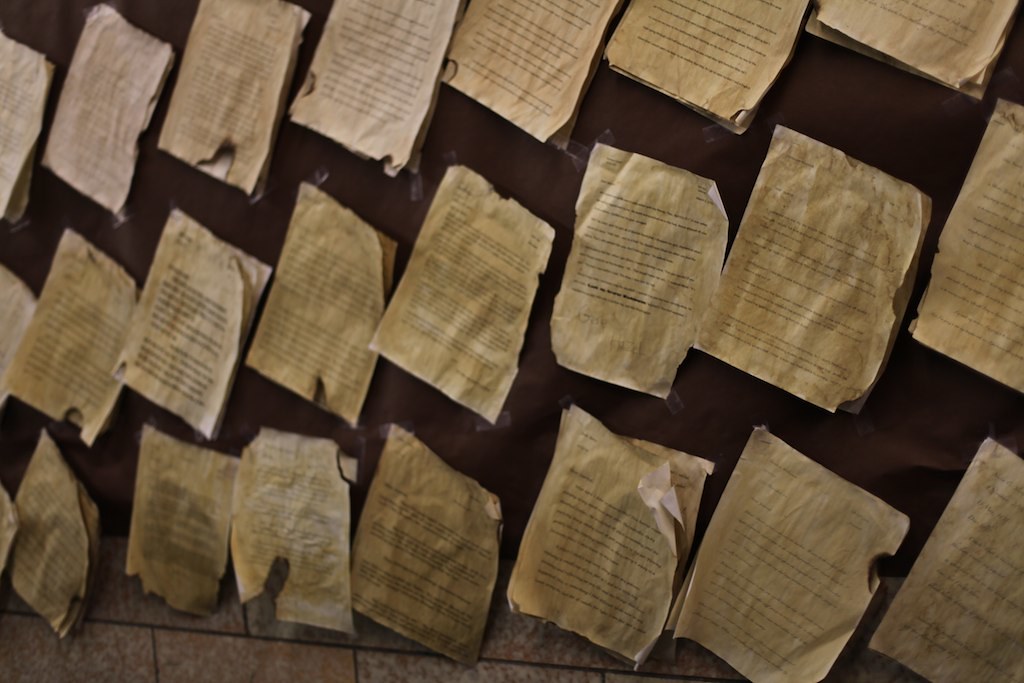

Over the course of my first two years as a teacher, I’ve discovered nothing turns out to be as it seems; initial shining moments give way to something far more complicated. My students are surprised and laughing in some moments, and broodingly vicious in others. Their work, that I meticulously hung up in September, has now grown curly on its bulletin board. At least by now, the job has taken on steady contours; my hopes have adjusted. Administrative tasks prove just as tedious as in the beginning; colleagues are just as coffee-stained. The physical building has changed little.

What does it mean to be in a second year as an urban public school teacher? It means I’m near the end of the average career. This June, statistically, I might be expected to head to law school or bide my time in a temp job in Brookline. My students are low income and look nothing like me, in person or on paper. I am white; they are black and Hispanic. I read the Globe or Harvard’s alumni magazine; they read their phones on their long T-rides in the mornings.

This morning I’d walked into school at 5:30 a.m. with my bottom lids puffy from three days of little sleep. The morning routine went round in its usual circle. White board. Changed the day to Jueves for the Spanish teacher I share a room with. Moved the desks into a circle. Crossed the hall to the teacher’s lounge. Held the paper coffee cup between my teeth as I clutched a clipboard in one hand and my keys in another, unlocking and locking doors as I passed through them, as though I were a guard in a jail, or a keeper of important secrets.

By the time Kaynan arrives, his eyes like slits and smelling of his early shower, it’s 7:30 and I’m two hours into my day. It’s anyone’s guess as to which one of us will find the impending hours more exhausting. He settles into his overdue assignment, an essay on quadratic equations, and seemed as intent as my older brother did at the end of graduate school, sipping from his paper cup, and tilting his skinny frame over the computer. This fall, when he arrived, he finger-pecked at computers, refused to do homework, and was suspended from school three times for declaring, in one profane way or another, that the school pushing him too hard. Now, his hair cropped more closely to his head, his uniform unwrinkled, he seems physically resigned to the tasks at hand.

Sitting at my oversized desk, I understand the focus in his body. With no job security or teacher’s union, I, like most charter school teachers, work twelve hours a day and weekends, am expected to do home visits and show up at sporting events, write my own curriculum, revise it, and use my students as test cases for any number of hip teaching philosophies. I am in bed by 8:30, rise by 5, and generally live the life of a matron far older than myself. It’s a life that resembles that of most of my friends, because at this point, most of them work at this school.

In Boston, the themes running through charters run the gauntlet from high expectations to closing achievement gaps to serving as examples of innovative reforms to advancing the small schools movement to small business models. Charters are anti-tracking and pro-integration, pro-test and also pro-project-based community-enhanced learning. They are about individual creativity and also standard setting. In a school that is meant to do it all, and in which I am giving everything I can, it is easy to feel some days like I am saving the world, and others like I am driving myself into the ground chasing a fundamental impossibility.

Kaynan is likely to graduate from high school, and he is likely to go on to college. It is likely that this school has facilitated in him outstanding growth in a small period of time. Then again, so do the teenage years, and, in my humble opinion, he is an incredible kid. So, why is it so important that I work in this environment? Why does it seem so necessary for us to each lean over our desks, before there is light in my classroom window?

At their most basic, charter schools were designed to consume students. As an interesting side effect, they also consume teachers. Boil down all charters’ ambitions, ruminations, and proclamations, and you see schools whose mission is to distract kids from everything else in their lives. Imposing hours of homework each night, a longer school day and year, and adults who are simply around, creates a community that owns students and teachers. Purpose, that lofty term, can be encompassed, for this place, in the idea that, distraction can cure all kinds of ills. Like five-year-olds’, our tantrums are staved off by a larger sense of working hard, taking care of business, stepping up. Charters have to possess and consume the people inside of them, barring chances for deviance, and limiting interactions with dysfunctional families, shady peer groups, violent neighborhoods, video games and anything else that can derail a teenager. As a result, charters can’t subscribe to the rules that allow for job security at other places. They dissuade teenagers’ social lives, and teachers’ family lives.

Kaynan, despite his solid focus at this moment, has been a slippery student for the school to hold onto. A black male and talented musician, Kaynan has plenty of other communities to choose from. His neighbors attend the large public school down the street, where there is a thriving Somali community and more music facilities. These are kids he grew up with, survived elementary and middle school with, and split away from, to go to this charter school that sucks his time away, asking for three hours of homework each night, in a language his parents don’t understand. Kaynan used to threaten to leave almost every day, storming into my room angry about a discipline penalty, upset about a grade. We lost a third of male students last year, and teachers and administrators feel a scramble to mentor those who are left with us. The balance between distraction and dissuasion is a tough one to strike, and individual teachers cross the line every day. But Kaynan finds meaning in his work, just like I do. This charter school has taught him to care about what he produces, and celebrated his successes to such a degree that he finds it difficult to back away from this place.

I, like Kaynan, embrace my work here, find validation and meaning here, and, perhaps most importantly, begrudgingly appreciate that there is no end to the good I can be doing here. Though I wonder how long I can persist in a climate which is controlled to be all encompassing. How will I etch out my own social existence as a twenty-something with bars to get to, travel plans to make, and, in some ways, a self to find? The school allows a forum through which I can hide out, but also frees me to feel a kind of purpose that I take to be rare in this world, to chat and have fun with kids, to play basketball in my spare time, to read great literature and to reap rewards from every ounce of creativity and energy I can squeeze out of myself. The school day will start soon, and Kaynan and I both have to wrap it up. I would write more now, but I have work to do.

Photo by Tom Woodward, licensed under CC 2.0

- In the Spring Light - May 8, 2020