In the summer of 2021, each day for two weeks, I drove my 13-year-old son 30 minutes north of our suburban Boston home to a camp in Winchester, Massachusetts. The camp theme: Build Your Own Escape Room. Ten days of kids working together to design a series of elaborate puzzles and traps.

While my son and his fellow campers learned Morse code and crafted clues to stump their victims (parents, who would be ushered into their maze on the last day of camp), I waited at the Winchester Public Library like a dog on a tether, my life transpiring a stone’s throw away from the eldest of my three children.

But isn’t this what a good mother does? Sacrifice a bit of herself for the betterment of the progeny she chose to bring into the world? And anyway, it didn’t feel like a trap: I was sequestered, after all, in a beautiful library with historic Tiffany windows, views of a pond spotted with ducks and lily pads, and a table of recommended reading.

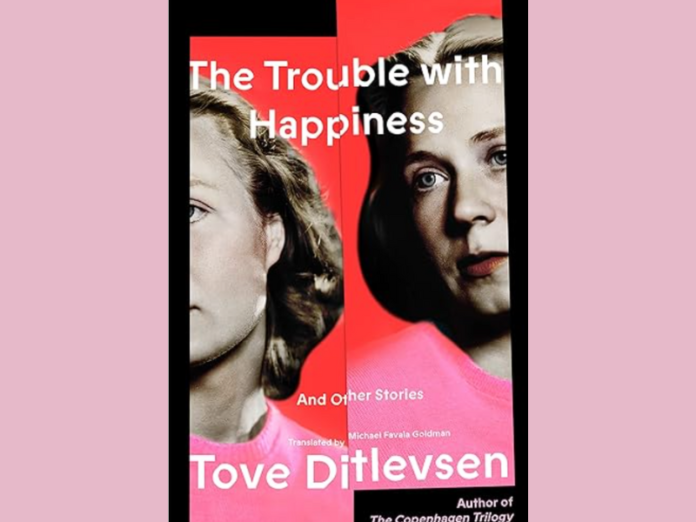

One book on that table stopped me in my tracks: a black-and-red hardcover with an artfully split photograph of a woman’s face, titled The Trouble with Happiness. I was not familiar with the author, Tove Ditlevsen. The flap explained that she was “one of Denmark’s most famous and beloved writers,” composing the stories collected in the volume — and now available in English for the first time thanks to translator Michael Favala Goldman— in the 1950s and 1960s. The writeup also mentioned her memoir, The Copenhagen Trilogy: Childhood; Dependency; Youth, selected as one of The New York Times’ Top 10 Best Books of 2021.

How had I never heard of the Danish woman who’d written about troubles with happiness? It had been thirteen years since my husband Andy and I had left his native Denmark after nearly three years of trying to build our new life together in Copenhagen. We met in graduate school in London when I — a Russian-born American — joined the university’s Scandinavian society on a whim. We fell in love and moved to Copenhagen a year later, in the fall of 2006.

In 2008, the World Values Survey declared Danes the happiest people on earth. In 2009, Oprah visited Copenhagen to witness the joy firsthand. But by the time her episode aired, Andy and I were living in a tiny old apartment in New York City. As I nursed my firstborn, I watched Oprah ooh and aah in a sleek, modern apartment that resembled the one Andy and I had left behind. And I wondered how and why the beautiful, socially progressive Copenhagen had felt like a maze whose code I couldn’t crack.

Why hadn’t I been able to find happiness in the happiest place on earth? I’d spent just a few years in Copenhagen, and a decade and a half more trying to figure out the answer to that question. Maybe The Trouble with Happiness could shed some light on where things — or I — had gone wrong.

Evil happiness

The Trouble with Happiness comprises two of Ditlevsen’s short story collections: The Umbrella, published in 1952, and The Trouble with Happiness, published in 1963. The original Danish title of the latter, Den Onde Lykke, in fact translates directly as “The Evil Happiness” — our first clue to Ditlevsen’s stance on the subject.

I began my Ditlevsen journey with the last of the 21 stories in the collection: the autobiographical title piece, “The Trouble with Happiness.” (Herein may lie one of my troubles with Denmark: a general resistance to the accepted way of doing things, such as starting at the beginning.)

The unnamed narrator is a woman of indeterminate age looking back at her girlhood and journey to becoming a writer. In the direct, part-confessional, part-journalistic tone characteristic of Ditlevsen’s prose, she admits that she was “only interested in young men and poetry” but was raised by a mother who “considered both of these hostile elements in our family.” The narrator’s father and brother, too, mock the absurd notion of a female poet.

Eager to escape her emotionally and creatively stunted life, the narrator sends poems to a magazine, which offers to publish two of them. “As if with the wave of a magic wand, this message changed my entire identity, my entire outlook on life,” she writes. Indeed, she gets what she dreamed of professionally, even convincing her brother to fill in for her and help their parents so she can embark on her creative life. She promises to return when she has made money as a writer — but never does. And yet the last lines in the story — and the collection — tell us that she has held onto an old music box that plays the song “Fight for all you hold dear,” the tune filling her with “unnamed sadness.” Andy tells me this a line from a song called “Always cheerful when you go,” which prescribes cheer throughout the journey — even if you reach the goal only at the end of the world. A clue to the emotional restraint (and resulting suffering) that Ditlevsen points to in her work.

The heroine — a writer like Ditlevsen — achieves creative fulfillment. Yet her unfulfilled connections and need for acceptance haunt her.

The pairing of professional success and personal despair struck a chord. Within months of arriving in Denmark, I found myself thriving in a new career as a copywriter. I understood the concept of “meritocracy” for the first time when, as a woman in my mid-twenties, I was brought onto the marketing teams of global brands as if I were an equal. Capable unless I proved myself otherwise: quite the opposite of my prior corporate experiences in the US.

And yet I couldn’t thrive in the world outside the office. I immersed myself in intensive Danish lessons, watched Danish shows, read Danish books — but it wasn’t enough. Ditlevsen’s heroine in “The Trouble with Happiness” writes: “Ours wasn’t a family that could ever accept new members.” Denmark often felt akin to such a group, happy to expand only if new members behaved like existing ones. It seems the very originality that my Danish clients appreciated — my American ability to convey a Danish brand’s uniqueness to a global audience — was a hinderance outside the office. From 9 to 5, Monday through Friday, I helped Danes stand out. The rest of the time, I couldn’t fit in.

“The Umbrella,” the first story in the collection, previews the consequences of reaching beyond the norms. It opens: “Helga had always — unreasonably — expected more from life than it could deliver.” The trouble with happiness, we learn immediately, is that it’s always just out of reach; ephemeral at best. Helga’s story centers around a coveted umbrella, though the frivolous object stands in for any desire. Once Helga acquires it, she wants to share the joy. Her husband, however, sees it as a threat. A jealous rage ensues. Afterwards, Ditlevsen explains, Helga “sat by the window as before, finally realizing that this was her place, and that everything was the way it was supposed to be.” She was never meant, in marriage of all places, to find the kind of ecstatic joy and inner transformation that a simple object could provide.

We the readers learn quickly that Ditlevsen will not be delivering happy endings.

The stories following “The Umbrella” reinforce the fragility of happy ideation. With near-devastating poignancy, they capture moments — disappointment, regret, frustration, acquiescence — that draw from a wide swath of human experience, but shared themes emerge, with the proportion of happiness to story about the same as salt to soup. A pinch here and there, quickly dissolving, leaving you thirsty for something that would satiate — but which Ditlevsen withholds.

Women struggle with the roles prescribed to them by society. Everyone struggles with the repercussions of all that goes unsaid. Fleeting, irreversible instants derail lives. Like the moment a husband tells a caller, on the phone, “My wife does not dance” and the wife, born with a limp, overhears and cannot move past the resulting shift in the relationship. Or the moment a young woman meets her boyfriend’s bitter mother and suddenly, catching his resemblance to his creator, cannot see the man she loved the same way: “the young woman looked askance at him with tears in her eyes for that mouth she had loved, which was now ruined for her.”

While each domestic drama surprised me with its uniqueness, the sense of life’s incompleteness felt familiar and oddly validating as I reflected on my own seemingly outsized reactions to micro-events in my Danish life.

The trouble with rules

The short story “The Cat” concludes with a scene between a husband who no longer feels he knows his wife, and the wife, who has suffered a miscarriage and channeled her maternal love toward a stray cat. The husband kicks the cat out, then goes on a desperate search for it. When he returns to his wife, Ditlevsen writes:

He felt something in his mind soften, and he wanted to go and put his arm around her shoulder, to be close to her in some way. Maybe she expected it; maybe she needed it. But then it occurred to him that the neighbors had probably seen him lying on the ground and crawling around between the bushes, meowing. He straightened his tie and walked back into the living room.

When Andy and I met in London, neither of us knew a soul. Whatever foolish things we did in Camden Town, where we wound up living together in our accelerated courtship, there were no neighbors whose opinions concerned us. In this anonymous, unobserved state, we became, I think, our truest, lightest selves, unconstrained by our histories or societal expectations.

When I agreed to move to Denmark, I knew nothing about the country’s rules and norms — but how different could Scandinavia be from the other places I’d lived and traveled in Europe? I didn’t do much research. This was before Denmark began to make global headlines with its happiness ratings, and best restaurant awards, and Bernie Sanders’ adoring proclamations. Before the globalization of Danish hygge sent candle sales soaring.

All I knew about Denmark was Hamlet.

In Copenhagen, I saw my own Danish prince transform before my eyes. He laughed less, worried more, didn’t want to dance as much as we had in London, didn’t want to go out to eat. Restaurants, in Danish culture, are a greater extravagance than they are in America or my native Russia. Emotions, too. But why couldn’t Andy — who had broken out of Denmark to work as a sheep farmer in New Zealand, then broken out once more for graduate school in London — shrug off Denmark’s cultural norms?

When my Danish teacher introduced our class to the concept of Jantelovn, I laughed it off as satire. Jante’s Law, a sort of Nordic social code of conduct, was concocted by Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose in a 1933 novel. Its ten rules include: Do not think you’re anything special. Do not think you’re as good as we are. Do not laugh at us. Do not think anyone cares about you. And so on, all to ensure the individual never rises above the group. Were the watchful eyes of the group reining in the individuality and warmth of the man I’d fallen in love with? Would he put his arm around my shoulder and kiss my forehead if his countrymen weren’t taking his emotional pulse?

Spending the first decade of my life in the Soviet Union in a bohemian, anti-Soviet family conferred a knee-jerk reaction to prescribed ways of being. In 1992, not long after we had immigrated from Moscow to Boston, my mother — who had by then navigated Soviet oppression of individualism for 30 years — sat me down and said: “There’s something you need to learn and understand. Here in America, originality is everything. Find what you’re really good at, and do it in the best, most original way you can.” With that, she prepared me to thrive in America, but not Denmark.

Rule-driven Denmark threw me. Learn your week numbers (the Danes number their weeks 1-52, and know them by heart for easier planning with other Danes, and to the chagrin of foreigners). Eat from the buffet and layer your sandwiches in the correct order. Top your herring with the right sauce. Wait at crosswalks for the light to change even when there are no cars in sight.

Today, as a mother with young children, I appreciate rule-following on the road. Yet with conformity in road-crossing and herring-topping come other kinds of obedience.

Andy recently recalled his Danish middle school teacher telling the story of a student who was used to getting 11s (the grades were on a 13-point scale) and got upset with his first 10. “How can someone be so ungrateful?” the teacher asked. “You should be happy with what you get.” The then-prevailing Danish view of ambition, Andy said, was precisely why he didn’t think too hard about leaving: first for New Zealand, then London, and then, with me, for America.

The difference is, of course, that Andy and I could leave, while Ditlevsen couldn’t, rooted as she was by familial ties, language, and both personal and historical circumstance. Her celebrity arrived in tandem with World War II, when Denmark was occupied by Germany. What’s more, having grown up in poverty, Ditlevsen spent much of her energy on survival rather than reaching for a different kind of life.

In her memoir, The Copenhagen Trilogy, Ditlevsen admitted that she detested change. Yes, she wanted to be published and recognized. But dramatic life shifts — like the ones Andy and I have had the opportunity to choose over and over — overwhelmed her.

Ditlevsen’s characters, too, often appear to grasp that rules and circumstances prevent them from blossoming into their true selves — yet they cling to the familiar. In “The Umbrella,” Helga on the one hand seeks an escape — and on the other remains attached to her mother, “because… she was a person, unlike everyone else, who never changed. It was a kind of respite for Helga…”

Happiness, Ditlevsen hints, goes hand in hand with the possibility of change. But rules and traditions, fearing extinction, interweave to create a lattice-style fence through which both happiness and change remain at once visible and unattainable.

The trouble with silence

Ditlevsen is fascinated with the way rigid norms shackle people — particularly women. But as much as she suggests that family life and social conventions are forms of inescapable hell, she continually points to something else at the heart of that inferno: a lack of communication. Her stories are, as much as anything, windows onto missed opportunities for connection. The Trouble with Happiness is a collection of things left unsaid, and the suffocating power of the unspoken.

Years after Andy and I had left Denmark, I asked a Danish family friend if he thought there was anything unique about Danish relationships. I was looking, maybe, for advice on how I could improve my own communication with my Danish husband. We were learning, but the road was bumpy: me always digging deeper to understand both my feelings and his; him preferring conversations about day-to-day topics and seeing my emotional rollercoasters as signs not of life but of trouble. And the Danish family friend said, without a moment’s hesitation: “Oh, we don’t communicate.” I laughed. He didn’t. He simply reiterated that, in his view, many Danes didn’t say what needs to be said to one another.

I filed this anecdote away as just that — a singular exchange brought on by too much wine on a hot summer night.

Then, not long after, I brought the topic of marital communication up with a psychologist who was helping me navigate the fear of flying I developed while living in Copenhagen. He asked me: “Did you ever hear the one about the Danish man who loved his wife so much, he almost told her?”

Ditlevsen could well have written the psychologist’s joke, though non-communication, in her work, is by no means limited to men. “The words stopped at her lips. They would never be spoken,” she writes in the story “My Wife Doesn’t Dance.” “We never expressed our feelings,” she echoes in “The Trouble with Happiness.”

And yet, when the mother of the narrator in “The Trouble with Happiness” sobs in grief at the death of her sister, the narrator admits, “Maybe I could have comforted her if she had expressed herself less bombastically. To me it seemed to make her grief appear unauthentic.” Damned if you speak up, damned if you shut up.

I might have found ways to work around Denmark’s rules, but I couldn’t work around the quiet. I wanted to chat with people in parks and with baristas and with librarians and with women wearing the same shoes I was. Fellow foreigners enthusiastically obliged but Danes seemed, for the most part, put out.

“Danes feel it’s their right not to be spoken to,” Andy reminded me. “Saadan er det bare,” he added, the phrase rolling off his tongue as smoothly as Schadenfreude does once you’ve said it enough. It means: “That’s just how it is.”

I happen to know that life-long connection can begin in a coffee queue, over the same shoes, or with a comment about a baseball cap, because this is how I’ve built my circle living in countries where such brazen reaching out is accepted. Ditlevsen, however, never got to live in such worlds.

In “My Wife Doesn’t Dance,” the wife desperately wants to know who called and prompted her husband to say that she doesn’t dance. Ditlevsen writes:

…she decided again from her profound loneliness to ask who had called – she had already

opened her mouth when her eyes met his. His eyes were good-natured, sad, and wise. They were searching penetratingly for something, maybe just a confirmation. Of what? The words stopped at her lips. They would never be spoken.

Such examples abound in the collection. No one wants to provoke an explosive fight that might ultimately lead to some kind of denouement; some greater understanding of one another. Instead, relief comes from returning to the status quo. That stillness is, it seems, almost like happiness. That outwardly harmonious quiet is, after all, the essence of hygge.

But language is the bedrock of connection. Ditlevsen knew this on the page but struggled to bring it to life. The page is far more forgiving than the human ear. Yet there seems to be a lesson here about how hard we are willing to fight to be truly known. Fight for all your hold dear…

Years ago, Andy and I read The Five Love Languages in an effort to pinpoint ours. But it isn’t so simple to divvy our love into acts of service, words of affirmation, gifts, quality time, and physical touch. Maybe that’s because every partnership demands a sixth language. Like a sixth sense. Something entirely new that evolves each day between two evolving humans. In our case, that language lives somewhere between Danish and Russian, between order and chaos, between practicality and whimsy. The language has to be tended to each day with the same care a writer like Ditlevsen devotes to poetry and prose.

While discussing this essay with Andy, I explained how Ditlevsen’s life and work have helped me understand my physical depletion at the buildup of all the things I felt I couldn’t say.

“There’s an expression in Danish,” Andy said. “Tie det ihjel. It means to silence something to death. Meaning if you don’t talk about it, it ceases to exist.”

“How have you never mentioned this?” I asked, amazed.

“It’s so commonplace I didn’t think there was anything special about it,” he said.

A few nights ago, after several full days home with my sick toddler, I had a few untethered moments to myself. Too tired to write, I returned to a documentary about Ditlevsen in the series “Great Danes,” produced by DR (Denmark’s version of the BBC). I rewatched scenes from her impoverished childhood, her pained youth, her disappointing marriages, her incurable drug addiction, her desires and failings as a mother. The narrator described her as “a woman who wanted to fill every role. She dreamed of being the good mother and doting wife — but above all, to be the beloved poet.”

At the end, Ditlevsen — looking and sounding wasted — says: “I think traditional marriage is dead. It’s no use mixing love with dirty laundry and shit-stained diapers.”

Yet we continue to mix them. Love, laundry, diapers. Andy, who grew up in a country where Ditlevsen’s voice continues to echo in the collective consciousness, is still married to me. Our love, though often frayed as our nerves, is far from dead. Communication seems to be the thing that neutralizes the laundry and diapers so they can’t eat away at the connection. When faced with the choice to silence things to death or hash them out, we’ve learned (through quite a lot of hard work) to choose the latter. Somewhere in that mix, writing happens, too.

Ditlevsen’s legacy

The short story “The Little Shoes” begins:

Helene woke early in the morning, feeling that her entire life was one big failure. She had

lost control over it. She attributed this paralyzing and depressing state to a variety of totally different causes, like when an animal gets caught in a trap and searches for a way out first in one corner, then another.

Helene’s husband had Helene quit her job as a child psychologist for tax reasons. She thinks he rmaid is seducing her husband. And she suspects her husband might love her daughter (his stepdaughter) a bit too much: he constantly buys her new shoes. In the end, Ditlevsen succinctly sums up Helene’s apparently inescapable escape room:

You can’t control your circumstances. You can’t control your fate. All you can do is avoid

people whose words stir things up, secret things, that absolutely must not be stirred up.

This sense of a woman’s lack of agency permeates The Trouble with Happiness. In her own life, Ditlevsen was repeatedly told that to get anywhere, she would need a man. Her happiness was nearly always in someone else’s hands, though she occasionally got to touch it. She made her way as an artist while constantly tethered to men who provided for her; one of them — her third husband, a psychotic doctor — also provided drugs, creating Ditlevsen’s addiction. It was a hopeless, dependent state that ultimately destroyed her: she committed suicide in 1976.

Still, over the course of her turbulent life, Ditlevsen published eleven books of poetry, seven novels, and four story collections. In 2014, her work finally became a mandatory part of the Danish primary schools’ literary canon.

What would have happened if Denmark had given her the honor — and accepted her as a “Great Dane” — while she was alive?

We can’t know the answer. But reading Ditlevsen, even in her darkest moments, reminds us of the light women writers enjoy today in what some have called the golden age for women’s writing. That light glows brighter still when we are reminded of the women who struggled to bring us to this moment, when our path is, while not paved in gold, at least paved.

I often wish I’d read Ditlevsen before moving to Denmark. I wish, too, that Ditlevsen could have known that Denmark would become, though not perfect, a place where women could far more freely shape their destinies. And I wish I could tell her that a Danish man raised on Jantelovn could also break free, learn to communicate the things on his mind, and learn to live with an unpredictable writer with little tolerance for rules.

The last part of Ditlevsen’s memoir is called “Gift” in Danish. Translated as “Dependency”, it is a word that means both “married” and “poison.” But surely Ditlevsen — who as a child loved her Danish and English lessons above all else — knew how gift translates into English.

Maybe the poetic journalism of unhappiness is the gift Ditlevsen handed to future generations. She designed her stories from the materials of her lived escape rooms, filled with traps and puzzles for others to solve. An escape room is a peculiar sort of gift to give someone. But to be shown how things are is to be shown how they can be made better, and that is a gift. It’s certainly felt like one to me. I imagine it has to Denmark, too.

- The Trouble with Danish Happiness - February 16, 2024