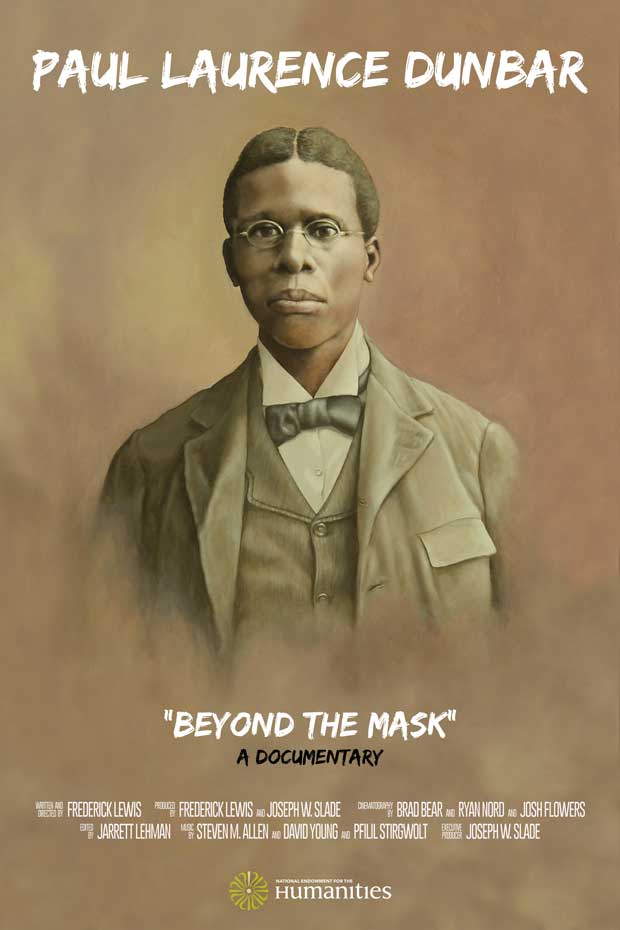

Paul Laurence Dunbar, Beyond the Mask, written and directed by Frederick Lewis

He sang of love when earth was young, /

And love itself was in its laze, /

But ah the world had turned to praise, /

A jingle in a broken tongue.

― Paul Laurence Dunbar, “The Poet”

Released in February of 2018, the two-hour documentary film Paul Laurence Dunbar: Beyond the Mask is the result of an eight-year research project co-produced, written, and directed by Ohio University professor Frederick Lewis to highlight the personal life and career of one of the most influential African-American poets, Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872- 1906). Dunbar’s legacy in the pantheon of African-Americans of letters is well-established; yet in many quarters, his literary gifts have historically been under-appreciated. Lewis’s highly entertaining and beautifully photographed documentary rectifies this heretofore lamentable circumstance.

Lewis was drawn to the project because Dunbar risks being reduced to a couple of his more anthologized poems, such as “We Wear The Mask.” Before starting the documentary project, that was all Lewis encountered of Dunbar. But as fascinating as his excellent work is, Dunbar’s life in itself opens up a chapter of U.S. history. Writes Lewis: “I was continually fascinated by the way Dunbar navigated [the] period following Reconstruction – commonly called the nadir of American race relations that saw the rise of Jim Crow – a horrific time of lynchings and legal segregation.”

Lewis’s narrative is wide-ranging, first examining Dunbar’s youth in Dayton, Ohio, where, as the son of former slaves Matilda and Joshua Dunbar, he attended several public schools, including Central High School, where he was a classmate of inventor Orville Wright, and the class’s only black member. He excelled at writing and became editor of his school’s newspaper and the president of its Philomathean (debate) Society, in addition to having his poetry published in the Dayton Herald. A profusion of visual artifacts, including videos, photographs, drawings, books, posters, broadsides, magazines, and sheet music, complement testimony from over a dozen writers, artists, and musicians, who collectively shed light on both the better- and lesser-known aspects of Dunbar’s life.

The storyline becomes even more provocative when Lewis details the racism that greeted Dunbar following his high school graduation. He was forced to accept menial jobs such as a janitor at the local National Cash Register (NCR) plant, an elevator operator in a downtown Dayton law firm, and, later in life, “book shelver” at the Library of Congress. Adding to his misery was the fact that he was tubercular and slight of frame, which forced him to leave each of those jobs after a relatively short period. This was dispiriting for Dunbar, whom eventual friend and patron, Frederick Douglass, (by then an ambassador to Haiti) named “the most promising young colored man in America.” In addition to Douglass, Dunbar would make the acquaintance of some of the most influential African-American scholars of the turn of the 20th century, including Booker T. Washington, W.E.B DuBois, and George Washington Carver.

Eventually entering journalism, Dunbar wrote passionately about the evils of the so-called “Jim Crow” laws that were established after the failure of Reconstruction. Lewis details an event in 1898 in Wilmington, North Carolina, where the only African-American newspaper in the city had been burned to the ground by white supremacists – killing more than a dozen residents. Dunbar responded in a column that was carried by several newspapers around the country: “For so long, the black man believed that he is an American citizen. Of that he will not be easily convinced to the contrary. It will take more than the burnings or lynching of North and South.” Dunbar understood that racism was not only endemic to the one region of the country, but to the nation as a whole.

In his writing career, Dunbar achieved popularity through poetry that captured the vernacular of the plantations his parents had toiled on. He wanted to be accepted more widely in literary circles, though, and not just as a “curiosity” as an African-American author. As the film shows, after the success of several of his poetry collections, Dunbar wrote a few novels featuring no black characters, which were generally disparaged by critics and the public. There was a prevailing racial animus in America that seemed to tell black writers to “stay in their lane” and write solely about black characters and situations. But if one did that, he was stereotyped; if not, his work was disregarded.

Prominent white authors who lauded Dunbar’s writing, such William Dean Howells, were not immune to the contagion of racist stereotyping. An 1896 issue of Harper’s Weekly featured Howells’s glowing review of Dunbar’s poetry collection Majors and Minors, in which he referred to Dunbar as “the bard of the Negro race”; but it was also infused with common racial canards about African-Americans. And, not long afterward, when Dunbar was reading before audiences in London, he was disappointed to realize he was looked up more as a novelty than as an influential writer.

Majors and Minors, as Lewis indicates, includes what is widely regarded as Dunbar’s most important and well-known poem, “We Wear the Mask,” which distills African-American frustrations and indignities into a powerful and compact metaphor:

We wear the mask that grins and lies, /

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,— /

This debt we pay to human guile; /

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, /

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Dunbar’s wife Alice Ruth Moore, an accomplished author herself, was the daughter of a mulatto mother and an absentee white or mixed-race father. As Lewis ably demonstrates, light-skinned Creoles of New Orleans identified closely with their French and Spanish descendants, but looked unfavorably at their African ancestry. This was true of Alice Moore, who, though she never hid her African heritage, understood acutely that there was a caste system in America based largely on skin pigment.

Narrated with passion by Barry Scott, Beyond the Mask commences and concludes with a solemn piano soundtrack, and a backdrop of students at largely integrated schools named after Dunbar, where they learn his plantation dialect poetry and develop a greater understanding of the man behind the name. The closing credits are accompanied by a magnificent musical rendition of Dunbar’s poem “When Malindy Sings,” sung by jazz legend Abbey Lincoln.

The five-hundred-plus archival images shown throughout the film — culled from over one hundred repositories — provide important context to the narrative. This context is further reinforced through numerous interviews with scholars, choreographers, artists, and authors, including a touching segment where Maya Angelou, speaking with TV personality David Frost, recites from Dunbar’s poem “Sympathy,” the lyrics of which served as the title of her famous autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

Among the experts Lewis has exhaustively assembled in this film are Dunbar scholars Akasha Gloria Hull, Joanne Braxton, Shelley Fisher Fishkin, and John Lowe, who are complemented by over a dozen distinguished literary critics, Dunbar biographers, historians and poets.

Throughout the film’s duration, Lewis reassuringly reveals that Dunbar’s legacy is still alive and well – in the arts, as in the case of Steven M. Allen, a composer of an opera based on the romance between Dunbar and Alice Moore, The Dunbar Operas; the brass ensemble Top Brass, that has set several Dunbar poems to music; the actor Phillip Cherry, an itinerant Dunbar re-enactor, who regularly dramatizes Dunbar’s verse in school classrooms; and the rap artist Jean P., whose song, “We ALL Wear the Mask” is a respectful nod to Dunbar’s poem. Dayton artist Walter “Bing” Davis, for his part, created a sculpture to commemorate Dunbar in the recently restored (and re-dubbed) “Wright-Dunbar” neighborhood of the city.

The beauty of the cinematography, enhanced by Jarrett Lehman’s expert editing, makes this already engrossing story even more compelling, and the inclusion of sound effects, such as the doors of the elevator Dunbar minded, a bellowing steamship horn, and the clanking of a blacksmith’s anvil, is a treat for the senses – making us feel as if we’ve traveled back in time ourselves. The elevator sound also augments the strength of the symbolism of Dunbar’s elevator, which, according to novelist David Bradley (one of interviewees in the film), is “a wonderful symbol when you put it up against the idea of the caged bird.”

According to Lewis, whose other film credits include a documentary of the artist and explorer Rockwell Kent, “What I really wanted to develop very carefully was the structure of the documentary – weaving contemporary segments about Dunbar’s legacy in with the archival materials that provide historical context and tell his biography.” Paul Laurence Dunbar, Beyond the Mask is a triumph of documentary filmmaking: a two-hour visual and aural feast that offers fresh and comprehensive insights into an African-American author who deserves greater recognition than he has to this point received.

—-

For more information on Paul Laurence Dunbar: Beyond the Mask, see DunbarDocumentary.com. The documentary is also available for purchase at Amazon.com.

- Dimitris Lyacos:Poena Damni: I: Z213: Exit; II: With the People from the Bridge; III: The First Death - July 31, 2019

- Paul Laurence Dunbar, Beyond the Mask - March 17, 2019

- When the Canon Takes Aim:A Review of Jordan Abel’s “Injun” - September 8, 2017