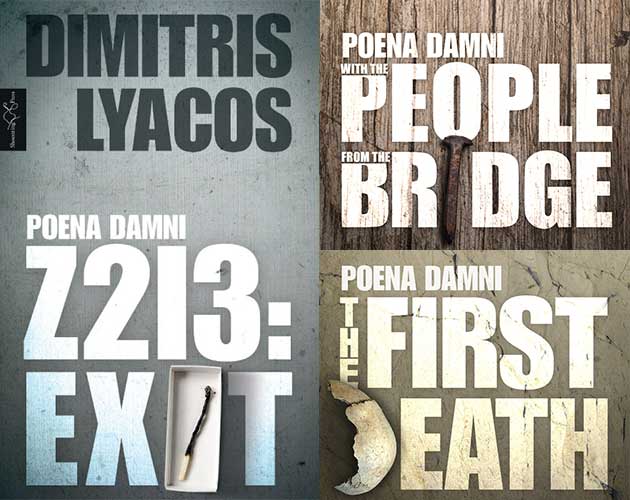

Dimitris Lyacos: Poena Damni: I: Z213: Exit; II: With the People from the Bridge; III: The First Death

Translated from the original Greek by Shorsha Sullivan

Follow the news these days, or take even a casual glance at social media, and you can easily be led to believe we are living in a hyper-chaotic era. Postwar alliances are under persistent threat of dissolving, and nations around the world, their populations fearing the influx of unwanted immigrants and the peril of nuclear holocaust, are turning increasingly to authoritarian leaders who promise to take “emergency” measures to steer their countries clear of perceived catastrophe. Anger, resentment, and a lack of faith in established institutions are the tinder stoking this potentially explosive set of circumstances.

It’s timely then that a new edition of Poena Damni, a trilogy of free-verse poetical volumes by Athens-born Dimitris Lyacos, and translated into English by Dublin native Shorsha Sullivan between 2014 and 2017, has just been published in a boxed set by Shoestring Press. (In all, the series has been translated into six languages). The title literally translates from the Latin as “indemnity”: rescue from loss; in this case, redemption in the face of one’s loss of faith in God, and the appreciation of the pain felt by tortured souls who’ve been condemned to Hell.

This monumental work of experimental poetry comprises three books published in various editions over a period of thirty years and is organized around “a cluster of concepts including the scapegoat, the quest, the return of the dead, redemption, physical suffering, [and] mental illness.” In the tradition of prominent postmodernist authors such as William Gass, Thomas Pynchon, and Samuel Beckett, Lyacos has artfully employed language to vividly accentuate the anguish his protagonists experience throughout the series.

Religion, classical literature, philosophy, and anthropology are all dramatically represented within the three slender volumes, which have inspired sister projects such as dance compositions, sculpture, video, opera, and other artistic media over the past three decades.

Lyacos’ characters are always at a distance from society. For example, the fugitive/narrator of the first volume in the series, Z213: EXIT, speaks from an imaginary future, a dystopian society with its own amoral and lethal rituals and realities, where time and memory are arbitrary and disposable concepts. Much of the imagery here resembles a Kafkaesque loss of control of one’s world, a scene as grotesque as that emerging from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting, The Triumph of Death.

Lyacos’ narrative is a wistful discursus on truth and reality, and conversely, untruth and unreality, through the narrator’s futile predicament of invisible existence:

“A few hours more, station, deserted, a dirt road leading into the town, mud, mud, blankets outside, mouldering corrugated houses, the shattered pylon further behind, not even a car, rubbish, two children setting fire to a heap, two or three other fires on the horizon, houses, …”

“Thought by itself tells you. Even if it is all otherwise and I don’t rightly remember, even if all things around me are fake. I am here, I am not there: two worlds alien to each other. And then, the space, distance, the road, even if I didn’t travel myself. The road exists …”

“Tracks only, a hazy memory and those images when I look at what I have written, tracks of footprints in the mud before it starts raining again. Uncertain images of the road and thoughts mumbled words, and if you read them without the names you won’t understand, it could have been anywhere, and then I spoke with no one and those who saw me no chance that they remember me.”

The characters are anonymous in this story, which involves people living in a communal situation to be taken away and thrown in pits — presumably to be buried alive. The unnamed protagonist is constantly waiting, in almost a state of purgatory, for his turn to join the others. The time of departure is described as “two thirteen.” References to Moses and Ulysses offer the impression that they are fellow travelers, questing through the unknown. But the inconsolable degree of torment, isolation, absurdity, fear, subjugation, and depredation that permeates this troubling tale is reminiscent of the Hell of Dante or William Blake.

The verse is both ethereal and powerfully evocative; time appears compressed, and is driven by the intensity of the fugitive’s condition in an apocalyptic setting. The description of night in one instance casts a beautiful pall over the scene:

“Voices and footsteps draw near then away. Then you start going down again as fast as you can, get there before break of day. More would die tomorrow. And some will know about you. Night cut in two by the yellow strip running through it.”

As reward for his suffering and demise, the fugitive/narrator can only hold to the hope that he will receive for his faith the favor of the angels:

“Everything will burn to the end, you suffer, but nobody is punishing you, they are just setting your soul free. Don’t be afraid, because while you fear death they will rend your soul like demons. Only calm down and you will see the angels who are setting you free and then you will be free.”

The second book of the trilogy, With the People from the Bridge, deals with a desolate landscape involving an abandoned train station very similar to that in Z213: EXIT. In this book, however, there is company of sorts: a group of three individuals, including the narrator, and two others, “LG” and “NCTV,” who stumble upon, and become involved in, an eerily macabre performance by a Greek chorus and other various performers on a “stage” set in front of a dilapidated automobile. The mind’s eye is tempted to compare this to a passage from Lord of the Flies, or a scene from the movie Escape from New York.

The narrative unfolds during the timeline of a calendar day dedicated to souls of the dead, or All Souls Day. The story references Mark 5:9 from the Bible’s New Testament, pertaining to the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac, one of Jesus’ miracles.

Resurrection and other Christian themes pervade With the People from the Bridge, which is a combination of prose narratives and monologues that are presented in a free-verse poetical form. “The bridge between the worlds” refers to man’s relationship between the temporal and the spiritual, with a recurring theme of salvation, such as when the narrator reads from the stage:

“For he saith in a time accepted

I have heard thee and in the day

of salvation, I have succoured thee

Behold now is the accepted time

Behold now is the day of salvation.”

The First Death, the last book in the trilogy, examines the temporal nature of existence. In Bruno Rosada’s On The First Death: Characteristics of Dimitris Lyacos’ Poetry, Rosada asserts Lyacos’ temporality is irreversible, in that it embraces the Aristotelian concept that we are mortal because this temporality is represented by a straight line: “… the existence of before and after, the sequential nature of this temporality determines the cessation of this existence, while cyclical nature is both symbol and substance of its endurance.”

The First Death presents itself as a booklet discovered by the marooned protagonist of Z213: EXIT. In this way, it serves to establish the continuum of anguish, agony, and foreboding uniting the trilogy’s volumes. For his part, the central figure of The First Death is living through his own dystopian world: a castaway reminiscent of Robinson Crusoe, his struggle for survival unfolding on a desert-like island. Its title is taken from the Apocalypse of St. John the Divine, in which are described first and second deaths: the first death referring to the perishing of the body, while the second death discusses the death of the soul.

The powerful imagery its verse evokes drives the intensity of the man’s doom-infused rage against elements that seem insurmountable. In its biblical references, The First Death is quite bleakly reminiscent of trials such as those suffered by Job, who endured the destruction of his family and wealth for what appeared to be no reason, but yet felt compelled to remain faithful in his plaintive entreaties to God. From Job 13, verses 23-24:

23”How many are my iniquities and my sins?

Make me know my transgression and my sin.

24 Why do you hide your face

and count me as your enemy?”

In this 2018 edition of Poena Damni, Shorsha Sullivan has beautifully and faithfully translated Lyacos, where staccato stanzas of verse interplay with narrative passages and longer, free-verse poetry to demonstrate the power of the story’s structure and form, and explicates both secular and non-secular themes that have consumed the conscience of humankind throughout history. This establishes continuity among all three volumes of the trilogy, and dramatically informs the gravity of the subject matter. With this translated edition, Lyacos’ timely and elegantly crafted verse is reaching new audiences and may offer consolation to many who are disillusioned by many of the alarming forces buffeting today’s world.

- Dimitris Lyacos:Poena Damni: I: Z213: Exit; II: With the People from the Bridge; III: The First Death - July 31, 2019

- Paul Laurence Dunbar, Beyond the Mask - March 17, 2019

- When the Canon Takes Aim:A Review of Jordan Abel’s “Injun” - September 8, 2017