Pangyrus presents The Sounding Board. What’s The Sounding Board? It’s politics writ large—and writ well. The makeup of society, the ways we interact, how cities get built, wars started, families reunited, poverty worsened or alleviated. This column will always challenge, always engage—and always be open to new perspectives. Send us yours.

_______________________

As a child, I would wait with anticipation for my parents to return to America from trips to the Soviet Union. Often they brought gifts like a few loaves of hearty brown bread or a wheel of briny, homemade cheese. Sometimes they also brought back notebooks or bits of paper with verses scribbled in Ukrainian.

These were the writings of dissidents and political prisoners whose work was banned in a systematic attempt to erase Ukrainian history and political expression.

Throughout the 20th century, czarist and then Soviet policies banned publication and education in the Ukrainian language.

Under Joseph Stalin’s rule, the Soviet Union killed at least 750,000 artists, writers, scientists, and intellectuals, as well as regular citizens, between 1936 and 1938. The Great Purge, as it is known, has since been well documented. But Soviet persecution of Ukrainians and other Eastern European nationals continued through the rest of the 20th century.

Ukrainians who fled felt responsible for preserving their native country’s intellectual and cultural heritage. My parents were among those in the Ukrainian diaspora who did so.

I am a Ukrainian American and a professor who studies the role of art in society; my work is a patient act of political defiance against centuries of cultural genocide.

Russia invaded Crimea, a Ukrainian peninsula, in 2014. Since then, I’ve worked closely with a Ukrainian nonprofit organization, the Development Foundation, to build community health and trauma programs in response to the Crimean conflict.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine again does not come as a surprise to most Ukrainian Americans.

Now Ukrainian Americans fear for the lives and safety of family and friends in Ukraine, and for Ukraine’s future.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said on Feb. 18, 2022, that East-West tensions are at their highest point since the Soviet Union’s collapse.

What it means to be Ukrainian American

Ukraine is home to about 42 million people. There are between 12 million and 20 million more people with Ukrainian heritage around the world. Many of these people fled political persecution or are descendants of those who did.

The Ukrainian American diaspora includes over 1.1 million people. Ukrainian Americans live primarily in big cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

Participating in Ukrainian arts and culture is a conscientious act of preserving national identity and culture for Ukrainian Americans, including my own family.

My father arrived in Rochester, New York in 1950 and joined a community that had Ukrainian language schools, social clubs, and an extensive credit union system specifically for the Ukrainians.

Members of this community published newspapers and created makeshift libraries in the basements of churches and social halls. They gathered Ukrainian language publications that were forbidden under Soviet law. These materials tell the story of people who identify as Ukrainian but whose history was actively suppressed.

Being Ukrainian American often means attending Ukrainian-language school on Saturdays, joining a Ukrainian choir or bandura instrumental ensemble, or memorizing verses of Ukrainian poetry and literature.

The idea of what it means to be Ukrainian American has changed since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

The Ukrainian diaspora pivoted from preserving history to helping build a future for Ukraine. Ukrainians are now free to express themselves as Ukrainians without fear of government reprisal. Many Ukrainian Americans maintain strong connections with family in Ukraine, and some have returned to live in Ukraine.

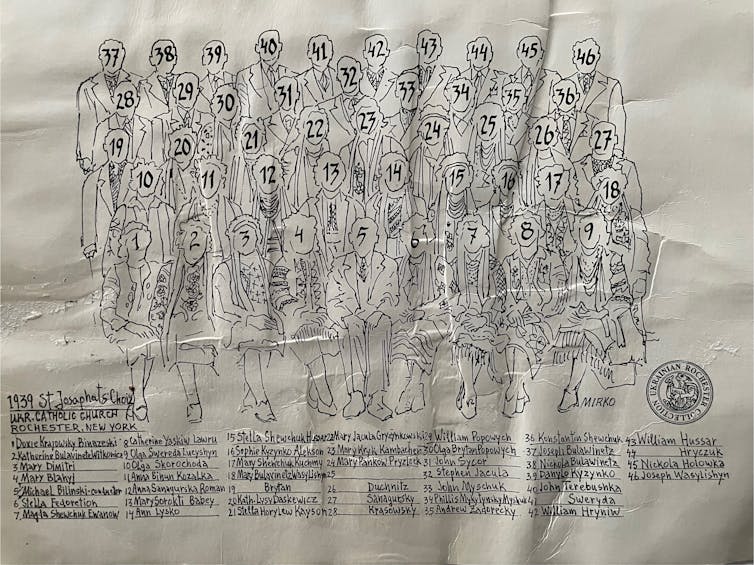

A rendering of a 1939 photo of a Ukrainian choir in Rochester, with singers identified by Wolodymyr Pylyshenko. Photo courtesy of Katja Kolcio.

A rendering of a 1939 photo of a Ukrainian choir in Rochester, with singers identified by Wolodymyr Pylyshenko. Photo courtesy of Katja Kolcio.

Preserving Ukrainian history

Ukrainians first came to the U.S. because of poverty and lack of land in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Another wave of Ukrainians followed between World War I and World War II, after the rise of the Soviet Union in 1922.

More Ukrainians migrated to the U.S. following World War II, which forcibly displaced 200,000 Ukrainians. The latest wave came after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1992.

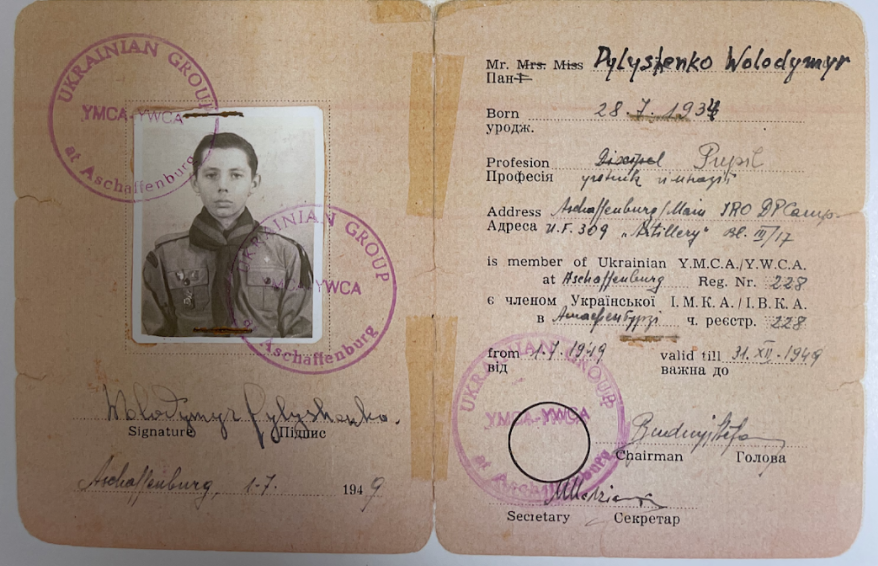

My father, Wolodymyr “Mirko” Pylyshenko, was among the Ukrainian American community leaders who worked to collect Ukrainian literature through informally circulated materials known as “samidav,” or “samizdat” in Russian.

As an editor and librarian at the Rochester branch of the Ukrainian Federal Credit Union, my father encouraged people to write their life stories. When a Ukrainian American died in Rochester, the family knew to bring their mementos to the credit union, or to him.

My father died of COVID-19 in February 2020. But in his final years he organized his archives. His extensive collection preserving the first 100 years of Ukrainian American life in Rochester is housed at the University of Rochester, and his archive of previously banned materials is now in Dnipro, Ukraine.

Schools in Ukraine, meanwhile, are teaching Ukrainian literature, political thought, and history dating from the 1800s. Ukrainian schools previously omitted major events like the Holodomor genocide, when Stalin starved an estimated 3.9 million Ukrainians to death in the 1930s.

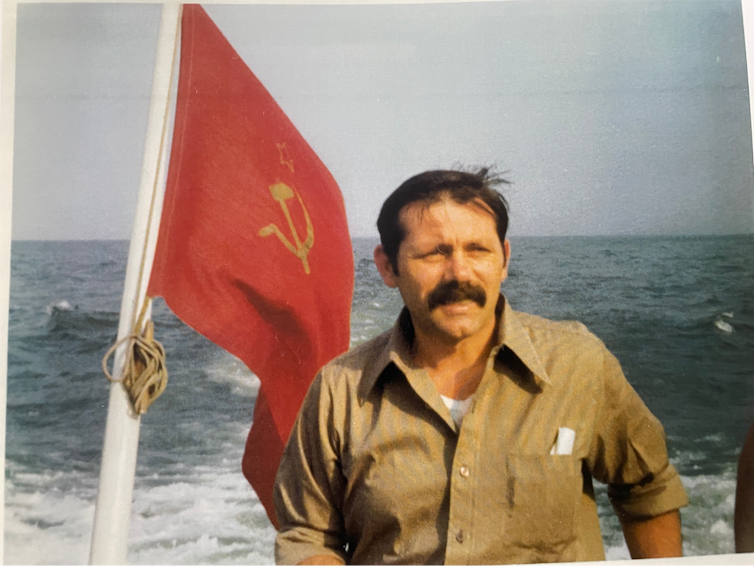

The author’s father, Mirko Pylyshenko, is pictured on a trip to Ukraine – then part of the Soviet Union – in the 1970s. Photo courtesy of Katja Kolcio.

The author’s father, Mirko Pylyshenko, is pictured on a trip to Ukraine – then part of the Soviet Union – in the 1970s. Photo courtesy of Katja Kolcio.

Russia’s attempts to suppress Ukrainian identity

In part because of their shared history dating back to the 9th century, Russia sees Ukraine as inherently linked. Putin published an article in July 2021, writing that Ukraine’s sovereignty is “possible only in partnership with Russia.”

“For we are one people,” Putin wrote.

Ukraine and Russia share a complicated history, both tracing back to Kievan Rus’, the first East Slavic state, which existed from the 9th century to the mid-13th century. The territory was centered in what is today Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital city.

But for Ukrainian Americans, the Russian invasion is a direct attack on the national identity they and their ancestors have passionately defended.

“You feel obligated to do something,” said Andrij Baran, president of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of North American Capital Region, in a Spectrum News 1 article on Feb. 8, 2022. Ukrainian Americans are closely following the news, calling their congressional representatives to support Ukraine, and praying for peace – while looking for ways to support the nation’s defense.

Roman Bodola, a Ukrainian-born parishioner in Riverhead, New York, explained this public interest in a local news article on Feb. 16, 2022: “Ukrainian people are strong. And they know they must stay strong and stop the Russians.”

![]()