Rivkah Yosselevska stood on a hillock outside the Zagrodski Ghetto and saw her mother.

Naked.

Shot in the head.

Then she saw her father. He refused to undress, so they tore his clothes off and shot him in the back. Then she saw her grandmother and grandfather. Naked, shot. Then, her father’s sister, shot, her two babies in her arms. Then, her young sister. She went up to them, holding hands with a friend. She begged to be spared, standing there, naked. He looked into her eyes and shot them both. They fell together, holding hands. Then her second sister. All shot to death.

Executed.

Then came her turn.

She stood, naked, her three-year-old daughter in her arms.

Why did you make me wear my sabbath dress? the child asked, as she helped her undress.

Whom to shoot first? he offered and, without waiting, shot the little girl, then her.

They fell in the ravine on top of dead bodies.

Then, she called her daughter: Merkele! Merkele! But Merkele was dead.

Then, she crawled on top of the bodies and wished she were dead, too.

Then there was silence.

Then she heard the Germans laugh, and then they left.

May 8, 1961. My school sends us on an assignment: An afternoon at the Eichmann trial.

Rivkah Yosselevska, head held high, face naked and dry, soberly recounts that Saturday nineteen years before. Facts, facts, nothing more: her family, the line-up, the shots, the naked bodies, the shots, the shots, her three-year-old daughter, her Sabbath dress, the laughter, the Nazi laughter.

We stop whispering, giggling, fidgeting, we school kids sit tight, unintentionally dead quiet.

Hannah Arendt.

Who she was, I discover later. The thick German accent, glasses down her nose, eternal cigarette dangling, eyes skeptical, voice throaty, authoritative, important intellectual, a name to remember.

Hannah Arendt is here too. Or is she?

Good question: in the midst of the trial she takes off for a 5-week vacation in Basel, Switzerland.

The Banality of Evil she calls it in The New Yorker:

Most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

Hannah’s protagonist sits in the bulletproof glass box and, like Rivkah Yosselevska, does not cry. He looks bored in his ill-fitting suit, thick black glasses, the nervous tick of his eye.

I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction. — Adolf Eichmann

Click here to read Nathaniel Gutman on the origin of the poem.

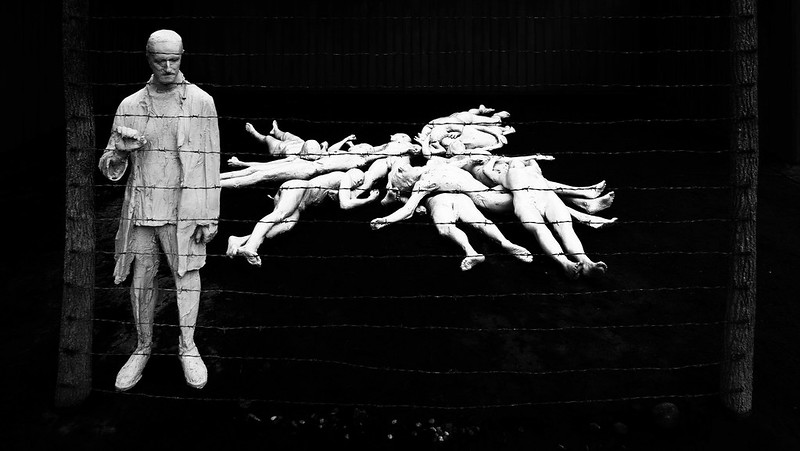

Image: “Holocaust Memorial, de Young Museum” by Christopher Michel, licensed under CC 2.0.

- Her Sabbath Dress - December 14, 2021