Why We Don’t Know Patrick Modiano

Last fall, Patrick Modiano was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. A French writer, he was hailed by the committee “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies.” Yet nobody in America knew who he was. The few Modiano books ever published in English disappeared from bookstores within a day and none were available again for weeks.

That an author at the forefront of world literature was not only unknown but nearly unavailable in America created a storm of commentary. The Modiano affair was rightly identified as emblematic of how little translated literature of any kind gets published in the United States each year. But focusing on publishing as the issue misses the larger, persistent, worsening problem: we are a society that appears to have little interest in what the rest of the world is saying. Having little access is only the symptom.

It is important to note that the Nobel Prize committee is not made up of Norwegian hipsters trying to one-up us on contemporary esoteric French writers. Modiano has enjoyed a successful career for over four decades. In spite of this, his few translated works were scarce, published by David R. Godine, a small Boston press. Nor is Modiano the only one. When French-Mauritian novelist J. M. G. Le Clézio, author of over three-dozen books, was awarded the Nobel in 2008, the same publisher was again one of the few to have published his works in America.

In telling this story, nearly every Modiano article embraced some version of the following argument: Translation is expensive work. Authors have to be paid for the rights to their books and translators must be paid as well. Talented editors are needed to oversee the process, and it can be difficult working in two languages. On the other end of the production line, books have to have audiences and if audiences are not there, losses can be significant. The risk of publishing unknown foreign authors, especially given the costs, is therefore simply too high to be commercially viable.

With hastily translated Modiano books now widely available, one could conclude that this is a sufficient view. Risk, supply, and demand are the problems. The problem, however, is far larger than scarcity alone, and far larger than just Patrick Modiano. The problem is that scarcity begets scarcity, with significant cultural consequences.

It is important to keep an eye on the real problem because the commercial argument gets less convincing the more you look at the risks and complexities involved in nearly any kind of publishing. Think, for example, of children’s picture books. Royalties have to go to the authors, but also have to be shared with illustrators, who translate stories into images. Talented editors are equally necessary and like all books, children’s books must find an audience or the publisher loses money. Yet there’s money to be made. Behemoth publisher Scholastic, which keeps a healthy number of picture-books in its mix of titles, earned well over $100 million in gross profits in the third quarter of last year.

Publishing is always a business of finding the right mix of titles, and there is plenty of evidence that books in translation can sell well. The Swedish-language blockbuster The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo sold over 15 million copies in the United States after being published by Knopf, a venerable publisher willing to take an occasional chance on something unknown from overseas.

Something, though, is keeping books from abroad scarce, even as the margins and flexibility afforded by e-books make publishing risks lower than they’ve ever been. Only 3 percent of books published in America each year were first written in another language. Of those, less than 1 percent are fiction, and most are classics like Crime and Punishment.

Part of the problem is self-fulfilling prophecy, surely. Seeing small audiences, large publishers leave much of the heavy lifting of contemporary literary translation to small presses. Without marketing budgets or the Nobel Prize, small presses rarely reach large audiences. A belief that translation is unviable begets the belief that it cannot and should not be done.

But at the heart of this is the question of why the audiences are small to begin with? And here we see another belief: that we, the English-speaking peoples, are actually leaders in advancing the stories of individuals across the globe. The paradoxical effect of this faith in our own preeminence is to undermine it: we assure ourselves of our leadership while having little interaction with the world’s great contemporary literature, little understanding of who is creating it, and few ways to figure it out. After years of devaluing the importance of translation, we are not just missing avant-garde things, but works we might all embrace and works we very much need. This perfect storm of self-reinforcing isolationism means that despite our easy access to technology, we are alone. We have lost touch with the world’s storytelling lingua franca.

The cultural expense of our inaccurate financial focus on translation is immense. When we lose the stories that draw us together, we lose shared cultural fabric and connections with one another. Calmed by our confidence in the democracy of our markets, devices, and platforms, our own creativity suffers and we hardly notice how little real contact we’re making. A reflexive disrespect for other cultures grows while our own narrative becomes an incoherent supremacist monoculture that steadily approximates propaganda instead of conversation.

We tell our stories. We read our stories. Nothing more. Screaming over the wall at high decibels, we are not listening.

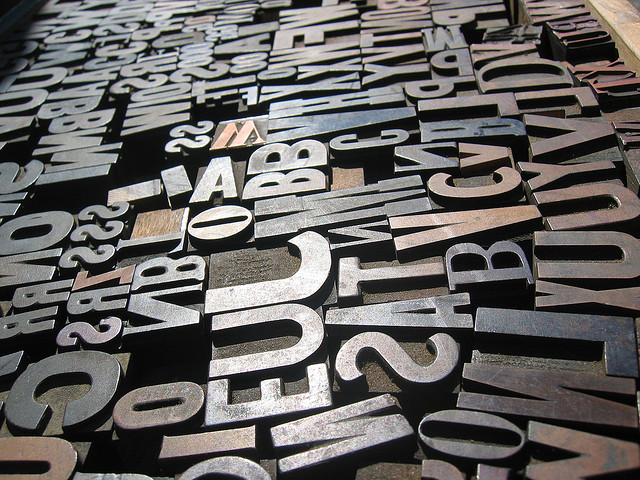

Photo: “A Sea of Type” by Evan P. Cordes; licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Losing Translation to the Marketplace of Ideas - March 27, 2015