1.

The pervert came to Independence on Labor Day, the day before school started. Independence is our street, where we all live. Upper and Lower Independence, but mainly Upper Independence, above the intersection and the gravestone store and the witch’s house.

Labor Day was when we got the news, at least. For all we know, he could have been living there already.

We were in Paul Ciofani’s basement, drinking IBC root beer and pretending we were drunk. Our parents were upstairs, in the backyard, drinking white wine, red wine, and Heineken.

Paul’s basement had a pool table, and a dartboard with a cork wall behind it. There was a NordicTrack machine and an arcade machine. The game was Gradius, and it took quarters. On a shelf behind the machine there was a pickle jar full of them. We asked what happened to the quarters after you fed them into the machine, and Paul said his dad had a way of getting them out. There was always someone playing Gradius when we were in Paul’s basement.

What we noticed first were the sounds of footsteps. It was our parents coming inside and standing together in the living room. Some of us went and got our sneakers and packed up our video games and Nerf guns. But no one came downstairs, and when we looked out the window we saw the Parkers’ car on the street in front of the house. Ryan Parker had been the oldest kid in the neighborhood before he went away to college, and whenever he was home he set out his street hockey nets for us to play on.

Mr. and Mrs. Parker stayed for an hour. No one came downstairs to get us, and it got dark, and we listened as, one by one, the dads raised their voices.

2.

The pervert had come to the Parkers’. He came to tell them that he was a pervert, and he was going to come to every house on Independence, one by one, to tell us all the same thing. He weighed three hundred pounds. He wore glasses. We imagined that they were smudged, wire-rimmed glasses, like the ones our music teacher wore. We tried to imagine what three hundred pounds looked like. Like Josef, someone said, and we laughed.

Our parents set new rules for us. We compared them on the walk to school. Paul Ciofani wasn’t allowed past the intersection, on foot or by bicycle. Sofia Winston’s dad had given her a can of Mace, which she kept in her backpack. She took it out and showed it to us. Peter Wiley’s mom had told him no more hiding games: no Capture-the-flag, Olly- olly-incomfree, Spud, or Sardines. If the pervert comes around, Paul said, I’d rather be hiding. Yeon Woo’s parents hadn’t told him anything at all, and he walked in silence, cleaning his glasses on his shirt.

“Does he have to visit when someone’s home?” Sofia asked before we went into the school.

How many of our parents were home during the day? Had he already been to our houses, and stood on our porches ringing the bell? Would he have looked through the mail slot to see if anyone was coming? Had he looked for our hidden keys? We knew where all of them were. Peter’s was underneath the doormat. Sofia’s was in a plastic rock. Paul Ciofani’s was underneath a piece of slate on his walk, but we used the back door, which was never locked. Mine was on a string on a nail just inside the mail slot. I could just reach it. I wondered whether three-hundred-pound fingers could fit through the slot.

3.

On Upper Independence, between the cross streets, our houses were connected by backyards. Our street had no government lines on it, just the chalk midline, which we redrew every summer from one intersection to the other. On school nights we played whatever we had enough people for. When the kids from the Townhouses and Lower Independence showed up, we usually played basketball.

There were hoops in front of Paul’s house and Peter’s house. The rim on Paul’s hoop was bent from when a snowplow ran over it, but it was at the dead center of the block, and that’s where we were playing on the first Friday after school started, when Roman rode up the street with Josef on his pegs.

Roman was one of the Russians from the Townhouses. He’d been here for two years. His English had gotten worse and worse, and he barely spoke anymore. He lifted weights with the other Russians from the Townhouses. They’d brought dumbbells out to one of the outdoor wooden fitness areas that the town had built, each with a little placard describing the exercises you were supposed to do there. The fitter Roman got, the less basketball he played, and now when he came by he usually just sat on the lawn next to his bike, in a black t-shirt and jeans, and watched the rest of us play. He was in ESL classes, which had the same after-school schedule as Special Ed.

Josef sat on the steps and changed into a pair of sneakers he’d brought in a backpack. They were purple and yellow, and he cinched up the laces but didn’t tie them. He tucked the ends back into the ankle of the shoe and pulled his socks up to his knees.

Josef spat when he spoke. He smelled, and he was hairy, and a little older, we guessed, than the rest of us.

“Josef,” Paul said. “Are you wearing perfume?”

“It’s cologne, you pervert,” Josef said. Then he grabbed the ball out of Paul’s hands and dribbled it into the street. He was a bad dribbler and his head waggled on his neck. We could see his feet sliding up and down inside his sneakers. He took a shot and missed, and no one went for the rebound.

Josef got mad easily, and when he got mad he eventually cried. He lived on Lower Independence, past the witch’s house, and usually had something to do after school, either synagogue, or tutoring, or walking his sister somewhere.

He hung out with kids from the Townhouses. They were immigrants: Koreans and Israelis who stayed for two years, Russians and Germans who stayed for one. We cut through the Townhouses to get to CVS, and we went there for the yard sales on Sundays. The other reason we went to the Townhouses was to look at cars for sale.

It was only my mom, really, who bought them. Our last three cars had come from there. A year ago, my mom and Paul Ciofani and I had biked into the Townhouses and down the main street, looking for signs in the windows. It was the first time I’d been inside a Townhouse, other than when we helped Yeon Woo move to Independence.

It was an Arab family, and only the father spoke English. There were grocery bags stacked everywhere, and huge suitcases open on the living room floor. While my mom spoke with the father, Paul and I looked around the first floor. In the dining room, and in every Townhouse I’ve been in since, there were cases and cases of bottled water. Even Yeon Woo’s family still drank out of a big Poland Spring bubbler in the corner of their dining room.

All Townhouses look the same: there’s a kitchen and living room downstairs, and two or three bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs. While we were looking around the house, a little boy came running down the stairwell into the kitchen, sobbing. There was blood seeping out from between his clenched fingers. The father spoke to him and pried open his hand. There was a deep cut across his palm. The father got out a bottle of rubbing alcohol and was about to pour it over the cut when my mother stepped forward and stopped him. After we bought the car, when we were driving back to Upper Independence with our bikes in the back, she said, “It’s like they’re still living in the Stone Age.”

It was just me and her in the house most of the time. My brother Morgan went to boarding school. My mother’s bedroom was upstairs and I spent most of my time downstairs. Once, when I got two B-minuses at midterms, she’d told me, “it’s your life to fuck up.” When Morgan was home, he liked to joke that she was retired from parenting.

Once in a while Josef’s dad would drive by. He drove a red Corvette convertible, and he’d leave it idling in the middle of the street. He’d talk to us out the window, and then he’d get out and take a few shots. He always wore white tank tops tucked into blue jeans and a leather jacket.

Josef shot with both hands, and always faded away on one foot, as though he were shooting at the buzzer. Josef’s dad shot normally, and we’d keep giving the ball back to him until a car turned onto the street and he had to pull forward or until he ran up and dunked it, signaling that he was done. We kept the hoop at the lowest setting, so that we could dunk. After he dunked he would call Josef over to his car and they’d talk for a few minutes in another language and then Josef’s dad would drive away, past the intersection and down Lower Independence to their driveway, where the street just started to slope downward. He always honked twice when he left. A little while later, Josef would pack up his sneakers and leave to eat dinner with his family, though he tried to keep it a secret.

Josef shot for a while and then we played Twenty-one and then Roman got up and took a couple of jerky shots, tucking in his shirt again after each one.

4.

It was a word we were still feeling our way around. All week, we tried it out in new situations. Josef was a pervert because of the way Paul said his fingers smelled after Josef fouled him in the face during a game of Twenty-one. “That’s pussy,” Josef told us. Later, Paul said it had smelled more like poop.

Paul’s Labradoodle Dennis was a pervert for getting a red rocket when Sofia scratched his stomach on the stoop. Roman wasn’t really a pervert for the way he dressed or talked about girls or porn, because that was normal for the Russians from the Townhouses. Peter, on the other hand, was a pervert for liking Sofia. He was the one who had started calling her Sofia again. The older kids had all called her Little Sweet. Her brother had been Big Sweet. Peter and Sofia talked on the phone at night, and we could hear the phones ringing when they called each other.

Ezra and Rachel, the two fully retarded kids at school, were both perverts as well. Ezra was a pervert because he dropped his pants and underwear all the way down to his ankles when he peed at the urinal. If you got caught peeing next to him, or even just coming out of the bathroom when he was in there, you were a pervert too.

We liked Ezra, but we hated Rachel. We could hear her barking from our classroom, and shouting “Fuck!” until the school officer came to get her. Other times she would cover her ears and scream until she puked, and then she would have a seizure. What made her a pervert was that she liked to stick her hands down her underwear in class, according to Josef, who spent half his day in Special Ed, and that she had once flashed her chest at a whole bathroom full of boys. Her nipples, they told us, were dark and hard-looking, like the caps of acorns.

In the short conversation we’d had on the walk home from Paul Ciofani’s barbeque that first night, my mother had said, “You should know that there’s a sex offender who moved into a house nearby.” After a few seconds she added, “Apparently he’s very fat. If you see him, don’t speak to him and come right home.”

“Why?” I’d asked, juiced up on energy from the party. I was surprised we’d stayed as long as we had. My mother didn’t drink alcohol or caffeine after four o’clock and she usually went to bed by eight-thirty. The only person she socialized with was our neighbor, Mrs. Huang, who didn’t speak English.

“Because he’s dangerous,” she said. It was strange to be outside together in the dark, and we walked slowly because of her hip.

5.

We made a map of the houses the pervert had visited so far. Three days after the Parkers, he went to Sofia’s neighbors’, who were elderly and who had no kids. Then he went to Yeon Woo’s, while we were at school. Yeon Woo said that his parents only spoke Korean, which wasn’t true, and that he didn’t speak Korean himself, which we also knew wasn’t true. When we did hear him speak to his parents, it sounded like he was yelling at them, and we were amazed that he could get away with that.

His parents had probably played dumb, he told us, like they always did when they didn’t want to speak to a white person. They wouldn’t tell him anything about the visit. We could imagine the scene on Yeon Woo’s porch, and all three pairs of glasses glinting in the sunlight.

A few days after that he went to Peter’s house. Peter’s grandmother, who stayed with them one month a year, was the only one home. There was a conversation: that’s all he knew. Did Mrs. Wiley know he was a pervert? Was he a pervert for old people, too? Peter went white.

It was an uneven square: two houses on one side of Upper Independence, one on the other, and one, the Parkers’, on a cross street, halfway out of our neighborhood toward the nicer houses at the edge of the golf course. Had he come from somewhere else? Was he just passing through?

6.

In the second week of school, we got homework. There weren’t enough kids to play anything except Horse and Twenty-one, until Friday, after dinner, when we all came outside. It was muggy and a few houses had put out citronella candles on their front steps, to keep us from getting Tsetse fever. We lingered around the stoops and jumped our scooters over manhole covers. We could hear an ice cream truck on the other side of the Parkway. Eventually someone got us into a ring and started eeny-meenie-miney-moe.

It was getting dark at night again, and we scattered into the half-light. It had been a couple of weeks since we’d been to our favorite hiding spots. Some were grown over, some had been re-landscaped, and some felt darker or smaller than we remembered from the summer. I climbed onto the roof of Yeon Woo’s garage and flattened myself against the warm shingles. Over the fence, I watched the branches shake as Sofia climbed the tree in her side yard.

Ten or fifteen of us hid in the trees and side yards and under the porches of the houses along Upper Independence. Someone else was ‘it,’ someone from a block or two away, and through his eyes we saw our neighborhood as a wild place, honeycombed with secret spaces. We waited and listened for footsteps and for the shrieks of kids up and down the block being discovered by the searchers.

I felt someone walking down the driveway and I flattened myself against the roof. It was a lone searcher, wearing flip-flops. I listened as he crept into the leaves between the wall of the garage and the fence, crunched a few steps in, and peered into the dark corridor. Then he stepped back out onto the gravel of the driveway. Across from me, two backyards away, I watched Sofia lower herself out of the tree and jog quietly around the far side of her house, moving spots.

It was getting close to the end of the game. I craned my neck. There was no motion in any of the yards I was facing, and no sounds of a chase or a discovery. There was a hunt going on. Then I heard it.

I swung from the roof down onto the picket fence and into the corridor between the garage and the fence. I crashed out through the leaves and followed the sound of the voice up the side yard. I slipped around the side of the house into Yeon Woo’s front bushes. They were big, hollow bushes, with room to stand inside.

Peter’s mom stood in the street. In front of her, lined up on the curb, were the rest of the kids from the game: possibly all of them, which would mean that I had won. Peter’s mom had been saying something as I came around the house, but now she was silent. She scanned the group, and turned to face Sofia, who was standing at the end of the group, breathing hard, the sleeves of her t-shirt bunched up around her shoulders.

“Where is my son?” Mrs. Wiley asked. It was true: Peter was missing from the group. I hadn’t won.

“Where the hell is my son?” she asked again, in a raspy voice. She turned down Independence, toward the intersection, and cupped her hands around her mouth. I slipped out of the bush and back into the side yard.

7.

It was evening and a few of us were sitting on Paul’s stoop, trying to get the tiny orange bugs to crawl from the bricks onto our hands, when my mother rode by on her bicycle. Everyone else had already been called to dinner. She had her helmet on, the big white one, with the mirror glued to the side. She was wearing her Discman on a lanyard around her neck, and it jingled against her ID card and all of her keys. She had her long denim skirt rubber-banded to her ankles so it wouldn’t catch in the chain. Everyone stared at her except me. She had her headphones in, and didn’t look up as she rode by and turned into our driveway.

A few minutes later, I heard my name. I said goodbye and walked across the street, past my house, up the steps and through the side yard to the back door of the Huangs’ house next door. My mother was already at the table, still wearing her Discman around her neck. Her headphones hung down next to the leg of her chair. She hadn’t paused her book-on-tape, and I could hear it faintly talking from the floor.

Mrs. Huang cooked us dinner on nights when my mom worked late. In exchange, my mom helped her with paperwork that she did a few times a year. Mrs. Huang sewed pockets into all my mother’s dresses, and every Sunday, after my mom was done reading them, I brought the newspapers over to the Huangs’ house. Sometimes I left them between the screen and the side door, and other times Mrs. Huang caught me and made me carry home dishes of food. We always took the two Huang boys, Richard and Kenneth, with us when I went to the eye doctor.

Richard and Kenny were younger than me and they weren’t really a part of the neighborhood. During the time when the rest of us were outside, they had piano lessons, art lessons, and tutoring. They were quiet except when they fought with each other, which was almost every night that I was over there. They fought with weapons, often the long metal shoehorns with the rubber grips that Mrs. Huang kept by the front door, and I’d seen them draw blood. Richard once kicked through the glass in Kenny’s bedroom window. They kept posters on the walls of their bedrooms, big pictures of the skeletal, muscular, and vascular systems of the human body, which they moved around to cover the holes in the walls.

Richard, my mother, and I sat at the table and ate white rice with tiny dried fish, thousand-year-old egg soup, and stinky cabbage. Kenny played the piano in the other room. After a while the piano stopped and the piano teacher let himself out the front door. Kenny came into the kitchen and sat with us. Mrs. Huang never sat down while we were eating. She just kept cooking, for some other dinner I assumed she had with Mr. Huang later on.

After dinner my mother and Mrs. Huang sat down in the dining room and put on their reading glasses and spread out papers on the table. Richard and Kenny and I went upstairs to play N64.

8.

The light in our basement came through small windows at the tops of the cement walls. It was almost dark out. I moved along the wall, putting toys into a white pillowcase. These metal shelves in the basement, next to the couch and the video game TV, were where our old toys ended up, and most of them were dusty and broken. There were Happy Meal collectibles and plastic knives and swords and old Nerf guns. I turned over a translucent, peach-colored squirt gun and warm water dripped out the nozzle. I dried it on my pant leg and put it in the pillowcase.

In the boiler room, on a rusty metal workbench, was my chemistry set. It was as I’d left it. I looked inside a plastic water cup, standing among the canisters of chemicals. Whatever I’d mixed together in it had dried a long time ago, leaving a dark ring in the bottom. There were little black pellets peppered across the surface of the workbench, and I touched one with my thumbnail.

I stopped at the top of the stairs, listening for my mother’s footsteps, and heard the chunk-whoosh of the upstairs toilet. I closed the basement door behind me and walked through the kitchen and foyer to the end of the living room, where Morgan’s bedroom was. It was dark now, and cooler on this side of the house, and I closed Morgan’s door behind me. As my eyes adjusted to the room, I noticed all around me the faint whitish-green aura of glow-in-the-dark toys scattered across the bookshelves and stuffed into the clear plastic toy bins at the foot of Morgan’s bed. I picked through the bins for the hundredth time, looking for things he wouldn’t miss. I rifled through his Pogs and added a few of them to the pillowcase. Finally, after staring at it for a minute, I put his saw-toothed slammer in my pocket. I went into his bathroom. He had two shower radios. I put the old one in the pillowcase.

9.

On Sunday morning, by the time we woke up, there were police barricades at the ends of Upper and Lower Independence. The Winstons had put out their tiki torches, and the Ciofanis had tied balloons to the crooked rim of their basketball hoop. Even the Parkers had propped open their screen door, and set out Ryan’s street hockey nets in the open square of the barricaded intersection. Sofia’s dad skated by on his roller skis, wearing his helmet and elbow pads, swinging his legs and clacking his long poles against the asphalt like a daddy longlegs. All of the families had moved their cars into their driveways, and we emerged, one by one, onto our pristine street.

The block party lasted all day. By noon the dads were grilling and the moms were walking in a group from lawn to lawn, pointing at flowers and bushes. We played street hockey and Spud and Twenty-one. Although the whole street was blocked off, the party was on Upper Independence. A few families walked up from Lower Independence and from the side streets around us, and in the afternoon a group of Russian families from the Townhouses arrived, shyly, with bowls of cellophaned food. An ice cream truck parked just outside the barricade at the intersection, and its song, which sounded the same volume no matter where we were on the block, inside or outside, gave us the idea to walk to Freezer’s.

I took some money from the Velcro wallet we kept in the piano bench. My mom left twenties inside for me to use when I needed them. Sometimes it was empty and I had to remind her, and lately she’d been leaving bigger and bigger amounts for me, less and less often. I always put back my receipts and exact change. The wallet was getting fat with coins, and I kept it hidden under the music books, though I was sure she never checked what was in there. Our house was so empty on days like this that it was scary to be in, wrapped completely in swaying daytime shadows and insulated from the noises of the street. I stayed outside as much as possible, until the last hour before dark, when the other kids got called in for dinner. Mrs. Ciofani or Mrs. Winston always invited me in to eat, but I usually said no. Sundays were a sad night to go to someone else’s house. They had chores and homework to do, and people got snappy with each other. Plus, I was embarrassed that my mother never thanked or even spoke to the other moms on the block. There was a neighborhood phone list, distributed by one the moms, but my mother never called their houses—instead she yelled from our front porch until I heard her and came running, from whosever kitchen I was in. (I kept our phone list, with other important numbers I’d added in pencil, in a drawer in the kitchen.) I was sure every family on the block stopped eating, food halfway to their mouths, waiting. The same was true of the intercom at the supermarket, and the PA system at school.

It was a long walk to Freezer’s, which we shortened by cutting through the Townhouses, along the back fence of a gated community next to the Parkway, and finally through the parking lot of the Pediatric Hospital. At the edge of that parking lot there was skinny alleyway, hidden from view, with a high gate at the end. There was a deadbolt on the gate, which had been broken and repaired so many times that we were never sure whether we’d be able to get through or have to turn back, undoing almost the entire shortcut. We always rounded the brick wall at the end of the alleyway carefully, in case whoever it was that shared our shortcut was back there, breaking through.

On the other side of the gate was the shopping center, with CVS, Blockbuster, the post office, a sushi restaurant, a bank, and Freezer’s Ice Cream.

10.

Russian boys—real Russians, who didn’t speak English and didn’t go to our school—were sitting with one of their sisters, who was talking to Sofia on her front lawn. They were sitting in a row of lawn chairs, with paper plates in the grass next to them. We didn’t want to leave without her, but we didn’t want to bring the whole group of Townhouse kids with us. And if the little kids saw us leaving, our parents would make us take them along, and we’d have to go by the roads. Josef had brought his own basketball and was dribbling it around in the street.

Yeon Woo arrived from his side yard and we explained everything to him. When Sofia stood up to go inside, Peter intercepted her at her front steps.

The Huangs came outside with their skateboards. I heard the sound of the boards on the street, and turned and waved. Kenny waved back, and they started skating up the street in the other direction, practicing ollies. I stepped off the curb to follow them, and heard the sound of Josef’s basketball behind me.

“Hey,” he said, not looking up from his dribble.

“What’s up, Josef,” I said. Over his shoulder I saw Sofia talking to her dad. He pointed to their car.

“What are you doing?” he asked me. Sofia opened the car door and fiddled with something in the front seat. Then she closed the door and walked back over to her dad and handed him his wallet.

“Nothing,” I said. “Skateboarding.”

“When do you want to trade?” he asked me. He feinted away from me and dribbled the ball low, by his ankles.

Sofia and Peter disappeared into Paul’s backyard. Paul and Yeon Woo stood in the side yard, watching me, out of view from the rest of the block.

I reached out to knock the basketball and just brushed it with my fingers. Josef slapped at it to keep it bouncing but it rolled to a stop against the curb.

“Like, tomorrow?” I said, backing away. The little kids were standing in a group under the basketball hoop. The Russians were still sitting in lawn chairs in Sofia’s front yard. No one had taken Sofia’s seat. Josef slapped at the basketball again. I turned and ran.

11.

The sun stayed high in the sky all afternoon. We ate our slushes on the bench in front of CVS. When we got back home, the dads were drinking Heineken.

We were playing Spud when the pervert’s car pulled out of his driveway. We froze and watched, and our parents froze and watched as well. It was a blue Honda Civic. We’d already looked into all the windows, at the neat backseat and the road atlas lying flat behind the rear headrests.

He backed slowly out of his driveway. Was the car sitting low on the driver’s side? He pivoted onto the street, pointing the nose of the car toward us, and paused for a long moment before putting the car in forward and turning the tires uphill, toward the intersection. On the other side of the intersection, we all watched silently. The Russian girl with the Spud ball held it tight against her chest.

He came to a full stop at the stop sign, and put on his blinker. He started to make the turn and then stopped. There were orange police barricades lined up along both sides of the intersection, blocking off the side streets from Independence. Our street hockey sticks lay in a pile next to the manhole cover. We held our breath. His car sat still, the right blinker a few feet away from the barricade, reflecting off the orange paint.

The barricades were easy to move. We’d discussed stealing one at the end of the party, so that we could close off the block whenever we liked. The only question was, who would get to keep it?

We stared at the driver’s-side door. What would he be wearing? Blue jeans and an American flag t-shirt, or a short-sleeve button-down, like the dads? A prison jumpsuit? Gym shorts, like us? Naked?

And then his blinker turned off, and the car rocked slightly, and he backed up, avoiding the pile of hockey sticks. He turned his wheels down Lower Independence, drove forward over the crest of the hill, and turned back into his driveway.

12.

Kenny and Richard Huang said their piano teacher farted on the piano bench, and they could feel the vibrations. They were planning to kill him. The two of them played N64 against each other while I watched.

Downstairs, my mom and Mrs. Huang were marking up a dress in the screened-in back porch room, where Mrs. Huang had her sewing machine. Mr. Huang was watching Chinese TV in the family room. He had his own couch, with special pillows, and he lay propped up on one side because he’d been in a motorcycle accident and had scars all over his body. We’d eaten dinner in the back yard, pork dumplings and cabbage and rice with hairy pork, which was my mom’s favorite.

Richard and Kenny were in a good mood tonight. We’d discussed different ways to kill the piano teacher. As the game loaded, I tried to untangle the controller cords in my mind. “Hey,” I finally asked. “Do you guys know about the pervert?”

We all stared at the screen as they selected their characters.

“He’s obese,” Kenny said after a while.

“My mom talked to him,” said Richard. His hands moved robotically on the controller. He flicked the joystick with his thumb, and pressed the buttons with his other hand using his index and middle fingers, Chinese style. Both of them had long fingernails and pointed fingers. Mrs. Huang wouldn’t let them cut their nails short.

Not only that, but in the bathroom they had tooth powder instead of toothpaste. I’d had to use it one night when I slept over while my mom was away. Only later did Kenny show me where they kept the Colgate, behind the mirror. There was dried toothpaste all over the mouth of the tube. When they brushed, they kept their mouths open and let the toothpaste drip into the sink.

“He came here?” I asked, looking up at Richard’s face. He puffed his lips out while he played, and his cheeks shook in rhythm with his fingers.

“He talked to my mom on the porch,” Kenny said from my other side. I sat back in my seat so that I could see both of them.

“What did he say?” I asked. Kenny got a combo on Richard and they both leaned forward in their chairs. Then Kenny said something to Richard in Chinese that sounded like “naka naka naka.” Richard broke the combo and won and Kenny threw his controller across the room so hard that it came unplugged from the console. Richard stood up and turned off the N64 and the TV.

“We don’t know,” he said. “My mom didn’t tell us.”

My mother was still in the sewing room with Mrs. Huang when I went downstairs. It was dark out, and I walked to the back corner of their yard, where there was a break between the chain-link side fence and the tall wooden picket fence that separated our yards from the yards on the next street over. I slipped through the opening and into my own backyard.

13.

At the end of Lower Independence there was a gravestone store. It was at the corner where Independence met the Parkway, at the bottom of the hill, which was the end of our town. We were not allowed to cross the Parkway.

All the stones faced outward. They stood in a yard facing the street, and at the center of the yard, backed up against a steep rock wall, was the gravestone store itself.

Most of the stones were blank, but some of them had designs, mostly Celtic crosses and Jewish stars, around the space where a name or date would go. One, our favorite, was engraved with the roots of a tree reaching downward, as though toward the grave and the coffin itself.

There were only a few gravestones with writing on them. One, at the outer corner of the yard facing the intersection, said “Custom Engraving.” Two smaller ones on the inside edge of the yard, facing inward, said “Rabinowitz.”

Behind the store, along the base of the rock wall, was a thin alleyway. It was hidden by a chain link fence with plastic slats in it. Inside the fence was where the owner worked on the gravestones, and those were the gravestones with names and dates, sometimes both dates and sometimes only one.

It was Josef who showed us the gravestone workshop. It was a short walk from his house, and he told us he’d explored it at night. He said he’d seen the man cutting a gravestone once, at night under a big light, using a jet of water, and that the runoff from the water jet was pinkish-grey, halfway between the color of the marble of the gravestone and the color of the asphalt where the water pooled.

From the front yard of Josef’s house, I could see the edge of the gravestone yard and the first row of gravestones. I walked up the driveway and knocked lightly on the door to the basement. Josef opened it immediately and I could tell that he’d been standing on the other side of the door, waiting, when I knocked.

14.

Josef’s basement had a cement floor and rock walls, like ours, though his walls were clean and painted and didn’t have the flood line, a few inches off the floor, where the water rose in our basement when it stormed.

There were cardboard boxes and cases of bottled water stacked against one wall. He led me into a second room, which had a carpet and a bed and a lamp on the floor. With the light on, I could see that Josef was wearing socks and a pair of his mom’s slippers that were too small for his feet. His heels hung off the back. His white t-shirt was stretched out at the neck, and he had the beginnings of a moustache growing at the corners of his lip. His sideburns went almost to the bottoms of his ears.

Josef sat cross-legged on the floor and I sat on the edge of the bed. From there I saw that he was wearing his yarmulke.

He leaned toward me and reached between my ankles and pulled out a paper Stop-n-Shop bag from under the bed. He uncrinkled the mouth of the bag and I leaned over, trying to see inside. He peeked in the top of the bag himself, then set it down at his hip.

“What did you bring?” he asked, and we both looked down at the pillowcase sitting on the bed next to me.

15.

I used to come to Josef’s house when I was little. I went over every day after school, sometimes in the backseat of the Corvette, and on weekend mornings when my mom went to the lab. I never knew why she picked Josef’s house, when there were so many normal kids on Upper Independence, and for a while at school I was associated with his family. I never saw her speak to his parents. Then I started skipping the ride home, and instead of walking to Josef’s I’d go straight to Paul Ciofani’s basement or to our own house, and fish the key out of the mail slot. (I’m sure Josef’s dad didn’t use the PA system to find me, as my mother would have.) Instead he called my mom at work, and later she and I got into an argument. I told her that Josef was retarded and that his sister Roni peed the bed and that their garage smelled like cigarettes. After that I started going straight home after school. Josef’s dad still waved to me in the carpool lane, but I avoided him and the rest of the family.

Josef and Roni still shared a bedroom upstairs. In the past few years, she had become popular in her grade at school. She was in the bedroom now, on the phone with someone. We’d heard the phone ring, and felt Roni jump off the bed to pick it up.

Peter was probably on the phone with Sofia. Yeon Woo was on the computer: I’d seen the glow through the window, in the den where he always sat with the lights off. Paul would be getting homework help from his dad. My mother was sitting in the kitchen at home, listening to a book on tape and cutting the shoulder pads out of the ladies’ jackets she’d bought at the Salvation Army.

16.

We traded a few small things. I gave Josef some action figures for a Nerf gun. We looked at each other’s Pogs. Some of the toys we had were the same. We traded Magic cards for a while, but neither of us really knew how to play or which types of cards were valuable. All of our Magic cards had come from the same yard sale in the neighborhood just past the Townhouses. Then Josef reached under the bed again and pulled out a white towel with something long bundled in it. I quit rummaging in my pillowcase.

Josef pulled back the edge of the towel and I opened my mouth. It was rolled up, but I recognized the white-green surface. It was the Nickelodeon Flash Screen. They didn’t sell them anymore, because they gave you seizures.

Josef unrolled the screen. At the center of the roll was the orange plastic lightning bolt, shaped to hang on the top of a door. It was attached to the screen by black strings. He stood up and held the screen up by the lightning bolt, and we waited as it unspun itself.

My cousins had one. Josef laid the screen back down on the floor.

“Josef,” I whispered. “Do you have the Zapper?”

“Of course,” he said, and reached down again into his bag. He handed to me a blue, wedge-shaped plastic remote with a flashbulb at the fat end. I felt its weight. It had the batteries in it.

“My uncle gave it to me for Hanukkah,” he said. “It’s pretty boring.”

“Yeah,” I said. The screen had minor crease marks. There was a small knot in one of the black lines that connected it to the orange hanger.

“Yeah,” I said again. I handed it back to Josef, and he held it up close to his face, as though his eyes were bad. Then he flipped a switch on the side. The Zapper hummed to life. We stared at it as it warmed up. The humming rose in pitch, and a green light lit up on the front, next to the flashbulb. Josef held it up in front of my eyes and it exploded in light.

As my vision returned, the first thing I made out was a glowing tetrahedron on the floor next to my feet. It was the screen, flaked on itself, partly covered by Josef’s towel, alive with a whitish-green glow. I blinked and Josef’s face came into focus. He was grinning.

“It works,” I said. He put down the Zapper and flattened out the screen with his slipper. The areas that had been shielded from the flash looked dark purple against the glowing stripes.

“So,” he said, taking off his slipper and pulling up his sock. “Did you get the duck?”

He meant the Beanie Baby mini duck from McDonalds. It was impossible to get in Massachusetts. It was in one out of a thousand Happy Meals. To get the complete set, which was worth a lot of money, you needed the duck, and without it the other animals were worthless.

In California, though, it was the other way around. There, the duck was one of the common ones. And I’d gone to California earlier in the summer. I went to McDonalds six times while I was there, and got three goldfish, a lizard, a lamb, and a duck. Josef knew about the trip.

I had the duck in a Ziploc freezer back at the bottom of the pillowcase, wrapped in a dishtowel along with the other nine animals in the complete set. The room was still swimming, and I rubbed my eyes. The screen glowed faintly on the floor. I didn’t say anything for a minute. Then something occurred to me and I stopped toeing the corner of the towel and looked up at Josef.

“Hey,” I asked. “Did the pervert ever come to your house?”

Josef wrinkled his nose and scratched his yarmulke.

“What pervert?” he asked.

“You know,” I said. “The pervert. He moved into the witch’s house.”

“What’s the witch’s house?” Josef asked. He glanced down again at the pillowcase between my feet.

17.

It was hard to know what my mom thought about the pervert. If she really was retired from parenting, then maybe she didn’t care at all. I suspected that she didn’t. My rules hadn’t changed when he arrived, but I hadn’t had many rules to begin with. I got five dollars for every A I earned in Math and Science, and ten dollars for every A+. I was not supposed to spend money on girls, because it perpetuated the stereotype that they were needy. And I was expected to come home when it got dark so that my mother didn’t have to look for me. She had arthritis in her hips and had trouble standing up after she’d sat down. I wondered if she really cared where I was. I didn’t get actual cash anymore for the grades; it just went on the tally that I took out of the piano bench. I bought things for girls as often as I could. Some nights, if we ate separately, or if I stayed late at the Huangs’ after dinner, I discovered that my mother had gone to bed without laying eyes on me. On those nights I stayed up as late as I could, playing computer games in the den, until the house suddenly became scary.

I searched for something else that Josef might like. Near the bottom I’d packed some old video games: Sega and N64 games that I didn’t play anymore, a racing game that I had two of, and a fighting game that I’d ended up with after accidentally returning one of my own games in the Blockbuster box.

The full set wasn’t actually that valuable, according to my mother. I’d revealed it to her when I got back from California. She said it was a gimmick, and asked me whom I planned to sell it to. “Collectors,” I said, and she said “Good luck.” None of us actually knew for a fact that we could get money for it, but there was something powerful about seeing the whole group of them together. The only other place we’d seen it was at McDonalds, in the photo above the Happy Meal display case. Even the display only had, physically, three of the most common ones: the flamingo, the bull, and the lizard. We assumed the employees would have stolen the duck a long time ago. I looked at Josef’s big hands, and tightened my ankle grip on the pillowcase. Through the cracked window, I could hear the whoosh of trucks driving fast down the Parkway at the bottom of Independence.

“Have you ever played Wave Race?” I asked, pulling out the stack of cartridges. He didn’t have N64, but I knew that he sometimes used the one at the Jewish Center. “Or you can sell them to Blockbuster or GameStop.” I held the stack out but he didn’t take it.

“My mom won’t let me sell games anymore,” he said. He craned his neck to see into the pillowcase. I rooted around, feeling for something I’d forgotten about. The reflection of headlights passed slowly across the far wall, and a second later they glared against the glass of the window. I asked Josef if I could see the Zapper one more time.

He handed it to me and I flipped the switch. It hummed and then whirred and the green light came on. I held my foot over the corner of the screen and aimed the Zapper. I pressed the button.

We rubbed our eyes and the room resolved around us. At the corner of the screen, glowing whitish-green, was the perfect outline of my shoe and laces. I put down the Zapper and reached into my pillowcase. Josef smiled. I pulled out the Ziplock bag. I’d pressed the air out of it when I packed it, and it was crinkled around the shape of the rolled up package. I broke the seal and I thought I could hear Josef inhale as the air rushed in.

For a while we played in the basement. We turned off the light and took flashes of the complete set lined up on his arm. His hands were so big that he could hold five in each palm, and I took a flash of him like that. From up the block, we heard the sounds of different telephones ringing. Josef took the Zapper from me and turned it upside down. There was a small lightbulb at the end, which lit up when he held another small button I hadn’t noticed before, and he used it to draw glowing bunny ears on the head of his silhouette. We drew other animals. We took flashes of shadow puppets, and drew faces on them.

We both saw it at the same time: red and blue lights, flickering against the far wall of the basement.

18.

We jumped off the bed and ran to the window. Standing on the washing machine, we could see, through cobwebs and a mesh of grass, the front yard and the street in front of Josef’s house. A police car, with its lights on, rolled silently up Lower Independence. It drifted out of our view from the little window and I stared at the pattern of flashing lights trailing behind it on the asphalt, waiting to see where it would stop. Or was the scene of the crime somewhere else, past the intersection? Josef had climbed down off the washing machine and was staring at me.

“It’s the pervert,” I told him.

He had the duck cradled in both of his big hands.

“He’s perverted someone in the neighborhood.” I pressed my cheek to the cold glass, straining to see. When I looked back, Josef’s face hadn’t changed.

There were no other windows on the street side of the room. I looked around for a TV, and then remembered the shower radio I’d brought from Morgan’s room. Josef walked across the basement to the bed and picked up the moose, placing it gently in his palm next to the duck. Then he turned both animals around to face me.

“Did you tell your mom you were coming over?” he asked.

I looked at the Beanie Babies and regretted trading them.

He asked again: “Did you talk to your mom before you left?” I wondered how his yarmulke stayed on his head, even when he bent down to pick up the turtle.

“My parents know you’re here,” he said. I pushed the switch on the Zapper and it began to hum.

We usually stayed away from Lower Independence. We couldn’t play games here, because of the hill, and we didn’t know the backyards or the insides of the houses. On Upper, we threw water balloons at cars that drove any faster than what we thought was safe. Down here, cars sometimes turned off from the Parkway and idled at the corner. And there was the witch’s house, and the gravestone store, and squirrels froze to death here in the winter. There was a hole in the stop sign that looked to us like it was from a bullet.

“If you didn’t tell your mom, she probably got worried again,” Josef said, talking to me from across the room. “I don’t think she knows we’re friends still.” The three animals fit easily on his palm.

“Do you want my dad to call her?” he asked. I walked over to the basement door and turned the knob. Outside, the air was muggy, and I itched my tongue against the roof my throat. Josef stepped through the doorway behind me. We walked through the gravel to the end of the driveway. Two yards away, the windows of the witch’s house glowed blue around the edges of the blinds. Past the intersection, on Upper Independence, the red and blue lights from the cruiser flickered against the hedges in our front yard. It was parked at the end of our driveway, and I could see that our front door was open behind the screen, and that the mudroom light was on.

“It’s your mom,” Josef whispered.

“It’s the pervert,” I whispered back, hushing him. The light was on in Josef’s family room, and I could see the shadows of his parents moving behind the curtains.

Just behind our hedges was a cherry tree, which I’d picked out with my mom at Home Depot. It wasn’t supposed to mature for several years, but I still checked it for fruit every few weeks. Somewhere up the block another phone rang, and in the silence that followed, when it didn’t ring again, I felt the whir of the Zapper in my hand. Josef and I stood at the end of his driveway, grinding our toes into the gravel and waiting.

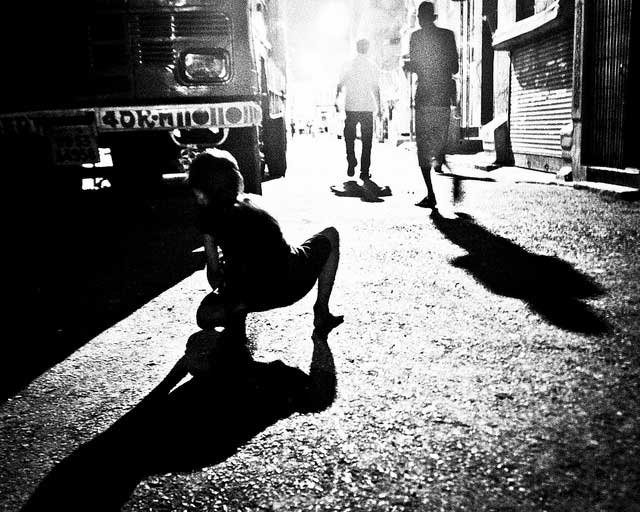

Photo: “Dream-Play” by Soumyaroop Chatterjee; licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Glasgow One - November 1, 2022

- The Pervert - December 23, 2015

- Five-Finger Discount - December 7, 2014