Bocas Del Toro, Panama 1931

In the house where Mama got sick, we five children, all under the age of twelve, waited for our fathers. Mama was a troupe singer and dancer. Dancer headwrap and dancer feet. Dancer fingers and dancer gaze. Now she faced death at the age of thirty-one. I was nine and in that year some woman from the town came and put her in a home where people with tuberculosis went. They told us not to visit, but that didn’t stop me and my little sister Chi Chi, my big brother Eliseo and my two little brothers Natali and Franklin. Every day, we walked the ten blocks and peeked in the doorway at the room filled with sick people, watched as Mama laid in a bed near the door and listened to her struggle to breathe; sounded like a whir in the wind. When we called, she’d sit up and stare blankly at our skirts, trying to figure out if it was really us or the ghost of someone that had passed. Then she lifted her eyes to look at our pigtails and the boys’ matted hair. When we got closer, she’d kiss us, tell us to go home, that she’d be there soon.

Our fathers never came, and no one watched us anymore. We did what we had to, beg for food on the Avenida Sonrisa, sit near women in the town square and go deep into their bags for colorful money. When we had it, I cooked rice, boiled it in the iron pot my mother hadn’t sold yet, ate with our fingers the way she did. But mostly we lived on cans of beans that my oldest brother Eliseo stole from the market and what the birds didn’t find on the Avenida Sonrisa. That was all we did for that month till the rent was due and the landlord ended it. Mama ended it too. On the same day that the landlord nailed a heavy lock on our door, and we brought Mama the last of the rice, we stuck our heads in the doorway and didn’t hear that whir anymore. Only beds upon beds of other people. People reading or coughing or lying still thinking of some far-off place where they would go when they closed their eyes for good. I like to think Mama went to some nice far-off place where she’d be thirty-one and beautiful and dancing forever. And where there wouldn’t be no landlords.

We just kept on this way, sleeping near the fountain in the town square. Every day the boys went into the woods to find food but never did. And me and Chi Chi sat on a bench by the fountain and put on a sad face for the people who strolled by. One day, when the boys returned, they brought back yellow flowers. Then my little brothers Natali and Franklin started in.

“We saw Mama today,” Franklin said, a week after we’d been living by the fountain.

“Mama gave us the flowers to give to you girls, they’re sun flowers,” Natali said.

The two of them stood in front of me without their shirts on, their little brown fingers gripped the flowers like they were holding spears. Soon they would accidentally break them, and I would cry if that happened. I snatched the flowers away and held them to my chest, rocking them like a baby.

“You saw her?” I asked. “Where, Natali?”

“In the woods.”

I closed my eyes and brought the flowers to my nose. They smelled like wild cotton and of any type of juice. I put my lips on them, nibbled on the grainy dark spot in the middle.

“Why do you have to lie,” Eliseo said. “If Mama was really around, she’d beat the two of you for lying.” Eliseo stared them down, biting his mustache that had started to grow in since Mama died.

“And she’d beat you for stealing,” Franklin started to cry.

“And she’d beat you for being half Jamaican,” Eliseo said.

“I’m not Jamaican.”

“Well, your father is.”

From the town square I could see the ocean, and I could also see where our town ended and another one began. Beyond that—trees and then the jungle. A fog had begun to roll in above the trees and it spread through the town like a cloud of powder. Eliseo and the boys hadn’t seen it, but me and Chi Chi did, and I looked right at it as it got closer. It crept up fast bringing the scent of the ocean and the jungle. The smell of swamps from the jungle and the sweet smell of sand from the beach. The fog covered us in no time and then rain started. Quickly, we gathered our bags and our money and the flowers so that we could find shelter below a tree nearby, but just as we did Eliseo passed out.

***

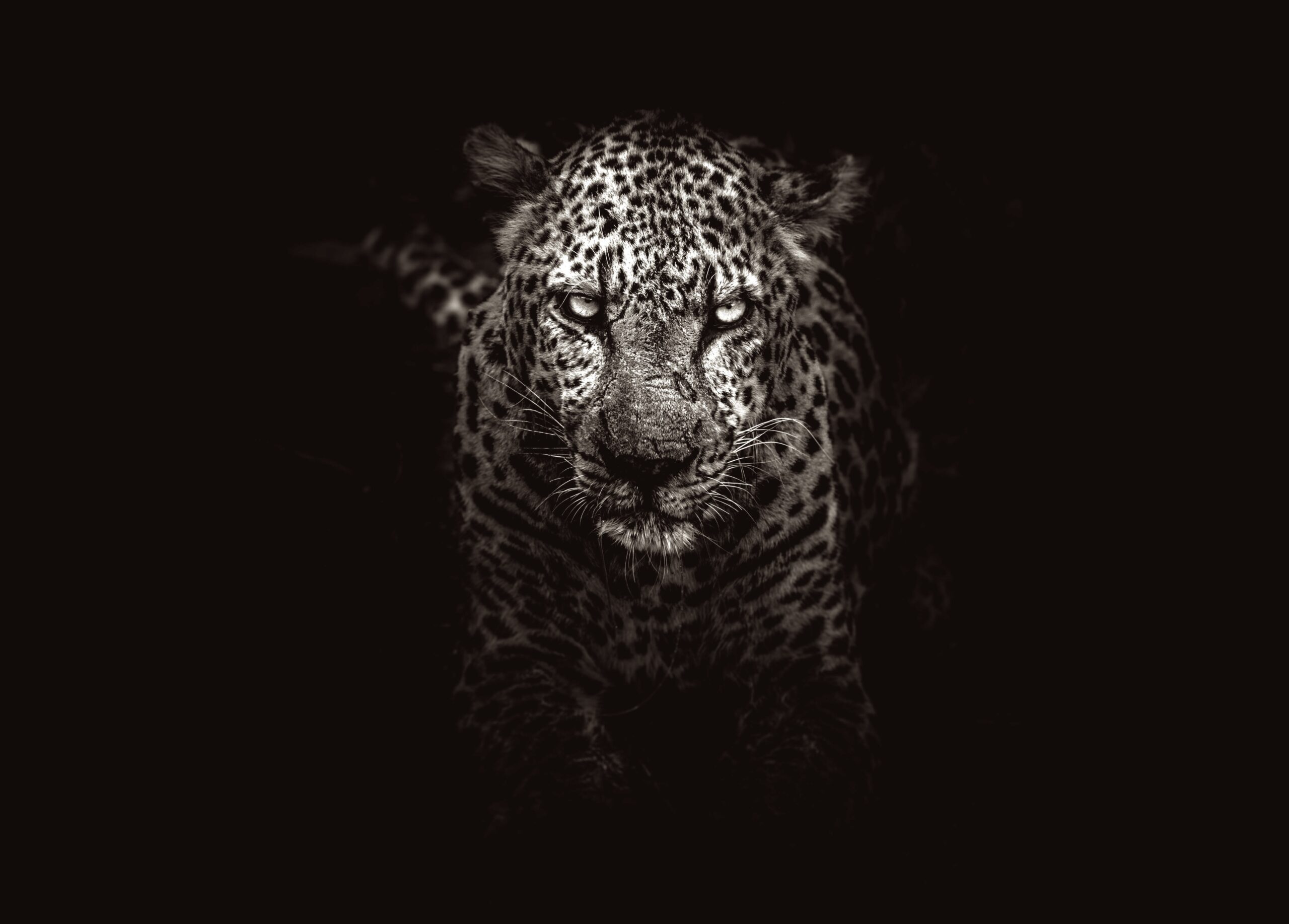

We found a house deep in the woods left behind by somebody who lived far away and didn’t care who stayed there anymore. It was barely standing, broken steps—rotting, leading to the empty bedrooms upstairs. Walls that seemed to have been knocked down by a flood. We just all found a place on the floor and slept, and slept, for hours. And when we weren’t sleeping, we were crying, and when we weren’t doing that, we were reassuring each other that we could stay there for a long time. But when the rain and the wind and the bugs shot in through the broken windows, and when the jaguars came into our yard, we knew we couldn’t live like this forever.

I told Chi Chi, “Listen, girl. If you cry too loud, they’ll hear us and then your daddy will come get you. But I’ll be left behind because my daddy would never come for me.”

And Chi Chi, six years old, would open her big eyes and shake her head, bury her face in my hands. And that was enough to hush her for a while.

We didn’t last but a few days in that house before a woman from the church came, riding a spotted horse and asking if we were the children of Maria Castellano, the black Colombian woman dancer. And Chi Chi said, “Yes.” And the lady took out things from her bag. All the things that belonged to my mother: her headwrap and her perfume; her sandals, the ones she danced in; all the things my mother had brought with her to the place where she died. And the lady also had another bag that was filled with cans of beans. When we saw this, we laughed. She was a broad-shouldered, wheat-colored woman, like an angel. And we jumped in front of her and kissed her on her knees. She said, “The thing I remember is her voice. A shame she’s not here. Her voice was magic.”

A few days later she came again with more food and more water. And she said, “I’m looking for your fathers, tell me your surnames.” And Eliseo said Brimley. And Chi Chi said, Martinez. And the two little boys of seven and eight, Natali and Franklin said, Borbua, because they had the same father. And when she got to me, I didn’t know who my father was. She looked at me and said, “You don’t know who your father is? But you look just like a Downer. You are a Downer, girl. I’ll find him.”

Because of this broad-shouldered woman, whose name I can’t remember now, for almost a week we lived like kings, and we would wear Mama’s clothes any chance we got, fighting over who would use her sandals or put on her wooden bracelets, the ones she wore to her shows. And we found pieces of dense wood that had broken off a fence, and knocked them against each other to hit a tune, dance like Mama taught us to dance in that African tribal way. And we sang in Igbo and in Spanish and yelled her name, our voices rising desperately into the sky. We were a sight. And when the jaguars came, they saw us and ran back into the jungle.

Soon, Mama wasn’t the only one that went. The two little boys lay down in corners and stayed there day and night. Brave boys, telling me they were okay, that they just needed sleep to feel better again. When the broad-shouldered woman returned, she put their bodies on the back of a wagon and brought them into the woods; told us to stay put in the house until she got back. But as soon as she was gone, the three of us went outside, saw the black smoke rising over the jungle. It rose quickly like shooting pillars, unfazed by the wind and the trees, and even the birds that flew by, flew around it.

When the broad-shouldered woman got back from the woods, she handed me her handkerchief so that I could wipe my face of my tears. I would never again see my brothers, only in dreams, and only faintly when I looked at myself in a broken window of our new house and tried to smile.

The broad-shouldered woman let us ride her horse and I stopped crying for a while. Chi Chi sat in front of the woman and I sat in the back. We held onto her as she steered the horse. Eliseo stayed in the house watching from one of the windows in the living room as we made slow circles in the yard. We must have been squeezing the broad-shouldered woman because she kept rubbing my hand every time I tried to get closer to her. She said, “There are other children to feed. You’re not the only ones. If I’m not busy, you’ll see me again soon. I’ll come back.”

Dying feels like the skeleton of a kingfish in your neck. After my oldest brother, Eliseo died, me and Chi Chi pushed his body across the living room floor and into the front yard. It had been only a few days since the others had passed, and we no longer had the strength or the need to dance. We just hummed the tunes now, forgetting some parts of them and feeling disgusted when we did. And when we finally remembered, we tapped into a place in us that felt amazing.

We laid our brother’s body near a tree in the yard, the grass was wet from the rain that had fallen earlier and mosquitoes buzzed in our ears. Quietly, we said our goodbye to Eliseo. He wasn’t sleeping when he went, he had died with his eyes open. He had taken every single moment, brave too like the rest of them. Or was it that just before he died, he had seen the others in the room, naked and jumping—full of breath, calling him to once again be closer.

When Chi Chi couldn’t close Eliseo’s eyes, we turned him over on his stomach. I wished so much that the broad-shouldered woman would come to take him away. She hadn’t visited us since Natali and Franklin, and we wondered what had happened. It was normal for people to help needy children in Bocas. There were always hundreds of us wandering the streets, picking at the dirt like abandoned puppies. An adult or the church or the saints in the town would find a way to help, even though they themselves were poor. But I needed the broad-shouldered woman now more than the rest of them did. I feared the jungle, the blackness of it, the night bringing sounds that were louder than in the day; but I knew no one would come for us at this time of night. We would have to wait until morning to even have a chance of someone coming. Only a crazy person would travel in that darkness, and I feared that too.

Despite this, I had to say a final goodbye to Eliseo and go just past the clearing to get the leaves we needed to cover him, giant banana leaves that would hide us when we played in the yard and didn’t want to be found. I grabbed Chi Chi’s hand and went to where a family of banana trees were; and I began to pull their leaves, feeling their fluids drip down the sides of my arms and down my back. As we did this, the noises around us deepened and quickened, forming an echo in the canopy above us like the inside of a cave. And as we got further, just a few steps further, some of the noises stopped, then grew louder and faster yards away. Suddenly, something appeared before us, its green eyes gleamed behind the brambles. I pretended it wasn’t there but when I looked away, it had moved to meet my eyes. The light from the moon revealed its dark spots, and it lowered its head and shot its shoulders forward, waiting for us to move.

“There is a jaguar there in the woods Chi Chi, girl. But don’t look, just walk back and we will be safe in the house.”

But Chi Chi ran and for the first time in my life, I followed my little sister, watching the back of her head, her plaits pulling like tattered reins that I pulled with my eyes. We ran over loose branches, pieces of broken fence, puddles of rainwater, never looking behind me because if I did, the darkness of the jungle would have made me lose consciousness.

I followed Chi Chi up the steps, and we hid in the closet of the farthest bedroom, but there was no door to shut us in. Rubber trees broke in the woods and the wind shifted our roof. In the closet, we coughed of tiredness and of pain; we held tightly together up against its wet walls that broke as we trembled. We listened for the jaguar and prayed for it to leave as it had before. But there was nothing to keep it from us; because it was my spirit that had called the jaguar. I had called it. I wanted the jaguar to take my throat and break it in two. But it had not just been the jaguar I called, if it had been lightning, I would’ve wanted it to strike this house while we were asleep and bury us in smoke.

At night if a jaguar was chasing something outside, we could feel its paws striking the ground from anywhere in the house; and even though we kept the front door shut, we feared that a jaguar would come in somehow, through a hole in the roof, or through some other part we had not known existed yet; entering from a golden room, a room of hell, that when I dared to look at it, would blind me.

Now we heard the jaguar running up the stairs, scraping the hardwood, going in and out of rooms, as if it had visited the house before, or even lived there. As if it had come to reclaim its home. Soon everything would once again belong to the jaguar, when it would swallow my face and make me disappear.

I heard it enter through the broken window downstairs falling on the shards of glass on the floor. It stunk of the swamps we’d seen on our hikes, of the broad-shouldered woman’s horse she let us ride, and of the fluids we’d rub on our arms that we thought would give us relief from mosquitoes but never did. And when I told Chi Chi not to cry, she quieted and squeezed my stomach.

Soon the jaguar stood before us in the dark, moving its nose around us like a dog. It’s body and tail shifted as if it didn’t quite know what we were or who we were. No longer did I know either; no longer did I know the difference between this life and the next. What was light or what was dark, what tasted good or what was dangerous to eat. I buried my head onto Chi Chi’s shoulder and felt the jaguar’s wet tongue on my hair. I shivered, the jaguar’s face touched mine, softly, without harm, yet I was weakened even more, locked in place as if its tongue had poisoned me.

“I can’t move,” I said to Chi Chi but no sound came out.

The rain fell harder now, and I could hear it landing on the empty cans we left in the other room. Even though my eyes were closed, I could still see lightning; lighter and darker shades flashed in my shut eye followed by thunder that scared me even before it broke. I got up to run, but when I opened my eyes, the jaguar was gone. I heard it again in the other room as it jumped through the glass of one of the windows on the second floor. When it landed, the sound could be heard anywhere, even on Avenida Sonrisa, and they’d know where we were and come for us, because we couldn’t scream. Still I wondered if someone would really come. I wanted to trust in that, but what was trust? We were lucky, the jaguar had left us alone. But I had no trust for anything or anyone. And it was not mercy either that the jaguar had for us, because my brother had been enough for it. The jaguar had eaten Eliseo. I did not have to witness it to know. But me and Chi Chi held hands and walked slowly toward the window, careful not to make a sound. We covered our mouths and stepped over the broken glass; and when we got to the window, rain and wind came in, moving the cobwebs on the walls.

It was a high window, and I could barely see anything. But I managed to stand on one of the empty cans and look down. Chi Chi stayed close, but the window was too tall for her.

“Is it still there?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“And Eliseo?”

I did not answer her. I held on to the windowsill and put my head outside, careful not to touch the cobwebs. Eliseo was in another part of the yard now, dimmer there near the brambles where we had picked the banana leaves. He was turned on his side. His stomach was burst open, his feet and legs moved side to side as the jaguar tugged at his skin and small organs. The rain fell harder now, and the water began to spread over the yard making little ripples in it like a lake. I wished that I could look into the jaguar’s eyes and make it stop, but I could only look at Eliseo and wonder what type of father he would’ve been because he was such a good brother.

The jaguar had not touched Eliseo’s face. I could see his bronze skin, his plump cheeks and his eyes, the face of a handsome doll. Just before the jaguar left, it raised its long tail curving only the very tip. Then suddenly it turned its face to the jungle, its nose pointing at something nearby. Quickly, it shot its tail to the ground then went to whatever was there.

That night we held each other in the closet where we had seen the jaguar. Neither one of us slept. We decided that we would never go to the front part of the house. Always entering from the back. We never again said Eliseo’s name, just referred to him as my brother, or him, or the oldest. And we prayed in the round blue night for the lady to come back for us.

Eventually, we didn’t go outside at all. We just stayed in and slept upstairs, and we closed the door to the downstairs, which smelled awful, still fearing that the jaguar would return. But it never did. It left us alone. We didn’t even feel its rumbles anymore when it chased things nearby. It left us alone now. Just like Mama did. They just all wanted us to be alone. Even God wanted that. Or was it that tuberculosis took the jaguars too? One by one it took the jaguars. It took our broad-shouldered woman away. It took our daddies away, and one day it would take our fight away too.

Click here to read Beto Caradepiedra on the origin of the story.

Image: By Geran de Klerk, Unsplash, licensed under under CC 2.0.