The first time I realized that I look like my mother was when she was dying. She was 91, in intensive care, and her face was gaunt and hollowed out. Already very thin, she was reduced to a nearly skeletal state, the result of a few days of neither drinking nor eating. This was my mother’s response to what I later learned had been a kidney stone and then, likely, a cardiac incident. She had been alone for all of this. After not hearing from her for three days, my relatives had finally summoned police to break down the door to her apartment, and they had found her, dehydrated, malnourished, and with her organs failing. I flew from Boston to Greece to reach her in an Athens hospital, relieved I had made it in time.

My mother’s death seemed imminent that day in the ICU. She looked, frankly, as though she was already dead. Her eyes were sunken, her lips were cracked, and her skin was pallid. Most of all, her face was more skull than face. The bones that made up her features were prominent and stark. Cheekbones, jaw, nose with the hint of a ball to the tip: they were all visible. And that was when I saw myself, in that seeming death’s head.

Some sort of paradox was at work there in the hospital. For my own face had always been rounder, fuller, than my mother’s, and it was this roundness that was said to make me look not like her but like my father. But now that my mother’s face had become even thinner, now I was stunned to see the strong likeness between us. It lay in the underlying bone structure, laid bare to me for the first time.

It might not seem strange for a daughter to notice her resemblance to the mother who gave birth to her and raised her. But around my mother, there was always a sort of assumption that she was unique, a one-off, a creature so astonishing that no one — not even her own daughter — could look like her. In my extended family, we held to three facts about appearance: my mother was beautiful, my father was handsome, and I looked like him. Most of the time, the equation left out my father’s handsomeness: your mother is beautiful; you look like your father. I agreed with these family truths. My mother dyed her light brown hair blonde, while my father’s hair was dark brown, like mine. My mother’s hair was thin and straight, while mine was thick and curly, a milder version of my father’s zig-zag kinks. My mother’s chin was rounded, but I had a cleft chin as a child, like my father’s.

A toddler song I used to sing made a game of the voulitsa my father and I shared. No-no Mamá voulitsa, went the final lyric, with the Greek word for dimple. In my voulitsa song, my mother’s smooth chin was a problem, the thing that excluded her from my little alliance with my father. But I don’t think she saw it that way. My father and I were the ones with the flaw, and she was outside our pair, perfect and unmarked.

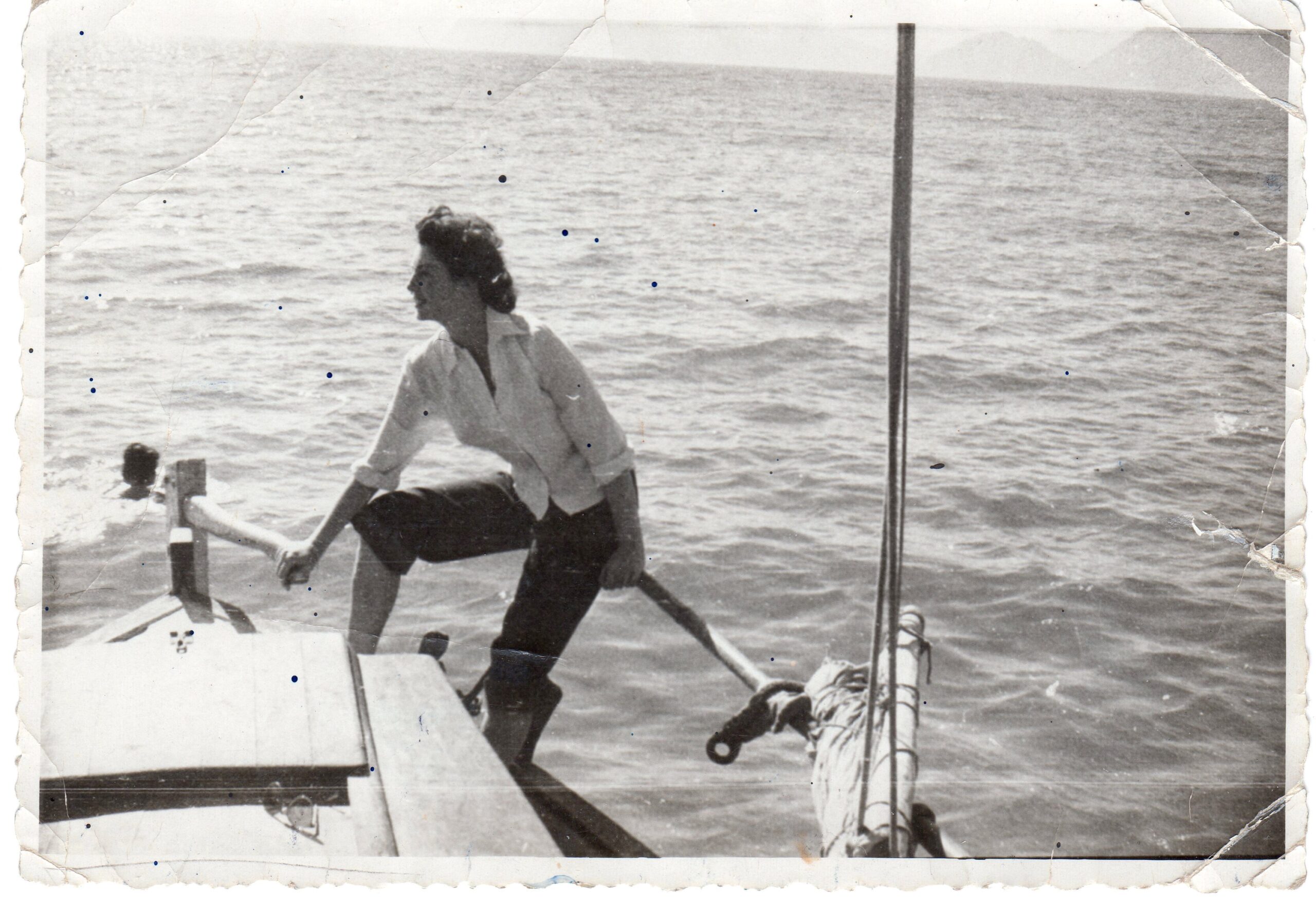

She was, in fact, a fairly astonishing physical specimen. Just weeks before she ended up in the ICU, she had been playing tennis. Earlier that summer at her vacation house on a Greek island, she had been walking a near-daily steep mile down to the harbor where she would clamber over the rocks to sunbathe and swim. She was 91 years old and was still doing laps in her technically perfect freestyle, the stroke that had earned her trophies as a teenaged competitor in her home city of Patras. She had engaged in all this athletic activity thanks to a mother who embraced a Girl Guides ethos of action and adventure. At a time when girls didn’t even ride bicycles, my mother had special skirts made so she could cycle, and she also took up the hiking, skiing, tennis, and horseback riding that she would enjoy her whole life.

More than her athleticism, though, my mother valued how she looked while being athletic, an attitude confirmed by the photo gallery that filled her home. With my father as mostly willing photographer, she posed for countless shots of herself carving a rooster tail on a single water ski, or smashing a tennis serve, or diving from a cliff into the Aegean, or skiing through Rocky Mountain powder. That she could do these things and do them well — and do them into the start of her tenth decade — was impressive. That her house presented dozens of these images to all visitors was something to think about. I once took a tally of all the photographs in her house and found that, of 59 photographs in frames on counters and shelves, she appeared in 41 of them. In 35 of those, she was alone, either posed in a bikini or caught in an athletic feat.

Rare was the photograph in which my mother was not wearing dark glasses. Nearsighted since her youth, she always felt her eyes to be a weakness in her beauty, and she had taken up dark glasses some time during my childhood, eventually wearing them indoors and out, all the time except when she was reading. Sometimes, I would catch her in the middle of one of the many books she devoured, and I would beg her to keep her glasses off, explaining how they hid not just her eyes but her expression. But she refused to rid herself of this accessory that turned her face into an ageless mask.

It seems to me now that my mother’s photo gallery was an extension of the documents that had traced her beauty since her youth, when she was a frequent subject of photo spreads in her local papers. These featured her, along with her cousins, for her athletic prowess, yes, but also for her looks. The three young women together were known as the Three Graces of Patras. When my mother was in her eighties, a society magazine published a retrospective, featuring her and my aunts in bathing suits and evening gowns. She kept the copy, dogeared to her page. Other women were included in that magazine, but my mother was clear that she and her cousins were the most beautiful of them all. She had a sort of absolutist notion of beauty. It was a zero-sum game in which any compliment to another woman became a diminution of her own status. The only exceptions to this rule seemed to be her cousins, models, and movie stars.

I think if I could ask her now, my mother would include me in that group. Especially after my father died and she was left with only me, her only child, she began to welcome me to Athens with the exclamation that I was pretty, a word as distinct from beautiful in Greek as it is in English. I became more closely hers, and it stood to reason that, as hers, I should be attractive. But when I was growing up, the message seemed clear: these other women in my family were beautiful and I didn’t look like them.

In my early teens, I staked out my own space, away from my mother’s world. Though I shared her love of sports, I cared about the challenge and the fun, not how I looked. A cousin the same age as me became a model in her teens, with her face on billboards throughout Athens. I refused to think about hair and clothes, let alone make-up. I told myself my intellect was more important to me. But the truth was that I cared deeply about what I looked like. I rolled my eyes at my mother’s issues of Vogue and Elle, but I paged through them with concentration. I took note of styles and sometimes tore out images to set aside as my own look-books, even as I insisted on the superficiality of the entire concept of fashion, even as I felt that none of it would be suitable for me.

By the time I reached my early thirties, I had little sense of what I looked like. As a teenager, as a college student, as a young wife and mother, I would have told you I had coarse dark brown hair, a cleft chin, and a round face. I would have told you I was pudgy. In a family that was obsessed with thinness, when I was measured explicitly against the cousin who would become a model, I felt myself to be enormous. Dazzled by the light of my mother’s looks, I could not see myself. Now, when I look at photographs from those years, I see my hair was curly, not coarse. My cleft chin was barely visible. I was at one point even too skinny. No matter what I looked like, my body had become strange to me, belonging instead to those who assessed it. I had so little idea of my own appearance that even now, at sixty years old, it takes me considerable effort to see the reality.

Sometimes, I look in a mirror and like what I see. Sometimes I think it possible that I am attractive, that a rank stranger who knows nothing about my personality could objectively label me attractive. But I can never utter that thought out loud — not to anyone. Writing these words here is difficult enough. I think this may be among the most impossible questions to ask someone — harder, even, than a question about money or religion: am I beautiful? It seems to me that only those who have some quiet belief that the answer is yes would ever dare ask it. Only those who truly know what they look like when no stranger is looking — who know what they look like when they are looking.

I mentioned this issue to a friend the other day and she immediately replied that she thinks she looks great. She wasn’t speaking about inner beauty. She meant quite literally she thinks she looks very good. She then laughed and confessed herself to be quite vain when it comes to video calls, and quite pleased with how she looks on them especially. I was aghast and, in a way, excited by her admission. Here was the first of perhaps many people I know who could say yes to their own beauty — and could do it without shutting the door on anybody else.

Then again, my friend did not use that word. She said she looked good. She said she looked mighty fine. Or damned good. Or some words to that effect. I wonder if there is something about that word itself — beautiful — that seems to make too great a claim, that shades too close to something more than vanity. Perhaps the word carries for us some sort of zero-sum game quality of its own, in which to utter it is to elevate ourselves above another. But does it have to? Is there always something wrong with claiming beauty for yourself? Couldn’t my mother have reveled in her beauty without needing to set herself apart and above anyone else? Couldn’t she have shared the space instead?

One month before my mother’s stay in the ICU, I brought my new partner to meet her during a vacation trip to Greece. I didn’t know it then, but my mother was already sliding towards illness. She had slept late and was still in her dressing gown when we arrived. She had not yet had time to put on her dark glasses. My partner told her how happy he was to meet her and said, in all sincerity, that he now knew where I got my beautiful eyes. My mother’s honest expression of surprise was one of the sweetest things I ever saw her do, a rare expression of vulnerability and openness. She said she hadn’t heard him properly and he repeated the compliment. To which she replied in all astonishment, ‘I do?’

I wasn’t so much surprised as puzzled. It was one thing for my partner, now my husband, to find me attractive. It was quite another for him to see my likeness to my mother. It was as if he had committed a transgression, uttered some taboo that must remain forever undeclared. But the thing grows more complicated again. For my future husband had singled out what my mother had always considered her weakest feature. Had my mother been wrong all these years? Had she worn dark glasses for no reason? What if her eyes were beautiful? What if mine were? Looking back on that moment now, I see us united, mother and daughter, in a shared vulnerability over the faces that we showed the world. Together we were taken aback; together we were, in that instant, deeply hopeful.

That day, my face was already the thinner face of a woman in middle age, already drained of baby fat and collagen. It was the only face my husband knew, having first met me in my fifties. But I hadn’t truly seen it yet. And one month later, when I visited my mother in the ICU, I still hadn’t seen it. I took my husband’s comment on our resemblance for a compliment motivated by love. I still thought of my face as the round one, the one with curves, not angles. How did I recognize myself in my mother’s gaunt and hollowed-out face?

Five days after I found her deathly ill, my mother recovered enough to go home — with a carer to keep an eye on her, cook for her, and make sure she took her new medications. Until she died at 93, I returned to Athens every two or three months, alarmed at how quickly she was dwindling, at how much more of her skeleton I could see with every visit.

I wonder if we can somehow see our own bone structure through the fat, the youth, on our own faces. I wonder if we somehow come to know what lies underneath. We’ll likely never see our own faces when they reach the stage my mother was at. Who among us would ask for a mirror in such a situation? And yet this might be when we have a chance to see our faces at their truest, when we might come face to face with the person we have been looking at our entire lives.

I’m not sure how I feel about the fact that I recognized my likeness to my beautiful mother when she was near death, at her least beautiful. It’s a complicated connection, like the complicated bond she and I had during her life. On the one hand, the recognition seems a gift, a pat of reassurance. Do I have beautiful eyes? Yes, you do. On the other hand, it seems a kind of malediction, as if I am allowed a vision of beauty only along with a darker message: this is what you will look like when you die. Perhaps it was a gift only my mother could give me. She and I could never be beautiful at the same time. In some strange way this was her bequest to me, bittersweet and late arriving. Here, it was as if her body was saying, I am dying. You can have a little beauty from me before you die too.

Image: Photo supplied by the author.

- My Mother’s Eyes - March 8, 2022

[…] so there are many situational irony examples in nonfiction. This excerpt comes from the essay “My Mother’s Eyes” by Henriette […]