Acclaimed Irish writer Niall Williams weaves imaginative, culturally nuanced tales on the meaning of family, community, love, survival and social progress in rural Ireland. With his lyrical, precisely paced storytelling and memorably complex, continually developing characters, Niall gradually reveals universal truths on love, loss, human frailty, and heroism — and on his abiding faith in common goodness. In this interview, Williams discusses inspiration, influences, future plans, and the flourishing of Irish literature in modern times. Pangyrus Fiction Reader Marlene O’Brien also asks Niall Williams about mythic imagination, placing a story between raindrops, and the Irish literary tradition.

Marlene O’Brien: You have mentioned that you do not plot or plan, but instead are “given a first sentence, and then follow the story’s logic.” Kindly comment on how those precious first sentences may have come about.

Niall Williams: Well, I do believe that they are in some way “given.” A sentence comes into my head. “It had stopped raining,” for instance, in This is Happiness. And something about that arrests me. And for the next while some part of my mind is looking at the implications of that sentence, aware or believing that there is an entire novel below or behind it, and I just have to stay thinking about it. To some extent, in my own working life, each book is born out of the one before and the need not to repeat myself.

So, having written a book with constant rain, History of the Rain, it seems now obvious that I would want to start a book with no rain. I wanted that book to have that fable-like quality that it seems to me we all feel for a glorious summer in our youth, so This is Happiness becomes a novel that takes place between two raindrops. That “once upon a time” that seems outside of ordinary time but inside the time of all story. And this, the whole novel in fact, is implied, it seems to me, by that first sentence.

MO: When you conceive of a story, how do you decide whether to make it into a novel, short story, or play? If your approach to writing differs for each genre, we would be interested in knowing how.

NW: I think that now the lure of narrative voice, the rhythm of prose, is so strong that playwriting is no longer an option. Getting a play right is so difficult, and so many things have to go right in all elements of the production — which has not been the case in my three plays — that I think it is a kind of a miracle if you attend a perfect night at the theatre. So, I am a prose writer, and the narrative voice that I recognize as the one I am most drawn to is made for longer fiction.

I want the reader to settle into the armchair of the narrative voice, to live inside the story, and outside of real time, if that makes sense. So longer fiction is what I am always aiming for now. I want you to take your time. In the case of This Is Happiness, for instance, I am trying to mirror the out-of-time meander of an evening at a traditional music session in a pub, when no one looks at the clock and we go on until we get to the end.

MO: Your storytelling honors the small gesture of kindness, the wearying chore in the service of others, the spontaneous act of good will, and the quiet moment sparking love. At the same time, your stories rise to the level of myth or epic. Please comment.

NW: Well, I don’t set out with these goals, these things emerge from the books in their own way. Of course they come from my own experience of people, and that experience, perhaps surprisingly, perhaps unfashionably, has left intact my central belief that human beings are good. There are good people literally everywhere.

To the other part of your question, I do think I have a mythic imagination. I have always been drawn to other writers, like Faulkner and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who have the same, and work out of a given geography. In Ireland, when in secondary school, we had to read the poetry of Patrick Kavanagh, who made this idea of the local, in his case a small farm in County Monaghan, as a gateway to the universal central to his work. In his poem Epic, he writes about Homer making an epic out of a local row.

MO: How has your life and sense of community in the townland of Kiltumper, County Clare, shaped your vision of Faha, the setting for History of the Rain, This Is Happiness, and Time of the Child?

NW: Christine [Breen] and I have lived here for forty years. It is forty years in April since we stepped off the commuter train in New York and came to live in the four roomed farmhouse that her grandfather left in the early years of the twentieth century. That decision to come to Clare has marked all of my and Christine’s work since then. Between us, we have produced twenty novels, plays, or works of non-fiction in those forty years, not to mention her many drawings and paintings, and the large garden in Kiltumper that is perhaps her greatest ongoing creative work, a blossoming thing being made out of the soil of her ancestors.

So yes, being here has mattered enormously. Firstly, just the energy you get from making the decision to take the chance on your own talent. The tightrope element of that. You are each day walking a tightrope that you are stitching into existence with words as you go. Then, the people here in our community were hugely helpful to us when we arrived. We could not have survived without their gentle guidance, and essential human goodness. That word again. And yes, some part of me wants to acknowledge that.

MO: Your stories of Faha have earned widespread critical and popular acclaim here in the United States, and we’ve heard that you may well remain in Faha for some time to come. If you’re willing, kindly share with us a hint as to your next work.

NW: Immediately ahead is the screenplay for the feature film adaptation of This is Happiness. I have started and am enjoying being back with Christy and Noe. The feature film adaptation of Four Letters of Love will go on general release this summer. The next Faha novel I will start in the summer; I am waiting for the first sentence.

MO: We are living in a golden age of Irish poets, novelists, playwrights and screenwriters, with you as a pillar. To what might you attribute this important moment in Irish literature?

NW: I really don’t know. It is true that there is a torrent. I think the education system has been excellent, with a strong emphasis on reading and essay writing. And the country honors its literary tradition. I don’t know of any other country where on the death of the national poet, Seamus Heaney, an entire stadium of people at a football match would burst into sustained applause.

There’s a long-wedded relationship of story and language and place here. Our identity is bound up in it. For my part, I can only feel an enormous gratitude that there are readers from many countries who have found something that speaks to them in the remoteness of Faha.

MO: Thank you, Niall, for taking precious time for this conversation with Pangyrus. We understand you rarely grant interviews, but your reflections will edify our thousands of readers and writers from across the globe. Personally, my reading groups can’t wait to read and discuss your next book. We live far from Faha, yet, with the universal truths it holds, the village feels intimately familiar. We’re also looking forward to catching This is Happiness in theaters this summer!

***

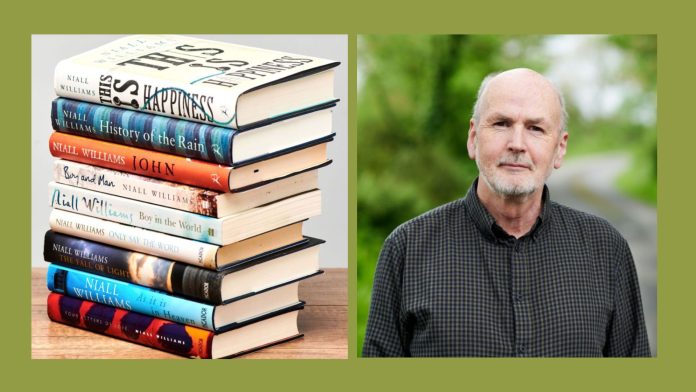

Niall Williams — Born in Dublin in 1958, Niall Williams studied English and French Literature at University College Dublin. After graduating and working in New York for several years, he and his wife, Christine Breen, moved to the cottage in Kiltumper, west Clare, that her grandfather had left eighty years earlier. They have two adult children, a dog named Finn and a cat called Thanks. Niall’s first four books, published between 1987 and 1995, were co-written with Chris and tell of their life together in County Clare. His plays were staged at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin and at Galway’s Druid Theatre Company.

Niall’s first novel was Four Letters of Love. Published in 1997, it went on to become an international bestseller and has since been published in over twenty countries. It was re-issued in 2016 as a Picador Modern Classic. His second novel, As It Is in Heaven, was published in 1999 and short-listed for the Irish Times Literature Prize. Further novels include The Fall of Light, Only Say the Word, Boy in the World, and its sequel, Boy and Man. In 2008 Bloomsbury published John, his fictional account of the last year in the life of the apostle.

History of the Rain (2014, Bloomsbury) was the first of Niall’s three published novels set in fictional Fara. The book was long listed for the 2015 Man Booker Prize and has since been translated into several languages, including Russian. This Is Happiness (2019, Bloomsbury) was nominated for The Irish Books Award and The Walter Scott Prize and was one of The Washington Post’s Books of the Year. Time of the Child, Niall’s latest novel set in the village, was published in the US late last year and has earned high acclaim from, among others, The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Times, and NPR.

- A Conversation with Irish Novelist and Dramatist Niall Williams - April 4, 2025