Published in collaboration with Artsfuse, Boston’s online magazine of arts reviews.

Gordon Parks may not have had a plan when the Life magazine photographer was assigned in 1950 to visit his hometown in Fort Scott, Kansas. The first stirrings of desegregation were roiling in the South, a low indistinct rumbling quietly unsettling a way of life largely undisturbed since the Civil War. Parks felt it underfoot. Was there evidence of hope for his classmates that racial oppression could or would be overcome?

The magazine’s first black photojournalist had been hired two years before. His colleagues? Names that adorn coffee table glossies… Margaret Bourke-White, Andreas Feininger, Alfred Eisenstat, Cecil Beaton, Robert Capa, W. Eugene Smith, to name a few. Like them, Parks had an eye for content and composition but it was his life experience that separated him most distinctly from his colleagues.

Now the Boston Museum of Fine Arts has assembled the results of his photographic journey home. Back To Fort Scott, a compact, affecting exhibition of meticulously printed black and white photographs, is like a grainy, retro speed bump between the museum’s adjacent galleries, which feature big, bold modern art, colorful and expansive. The forty two photographs hung on the walls of the modest Robert and Jane Burke Gallery on the third level, the images mostly 8 x 10 inches in size, require close observation.

Parks’ assignment was to take the political and cultural temperature of the effect of school segregation in the South. Parks reconnected with ten of the twelve of his ninth grade classmates with whom he graduated from same all-black Plaza Elementary School in 1927 and hadn’t seen since.

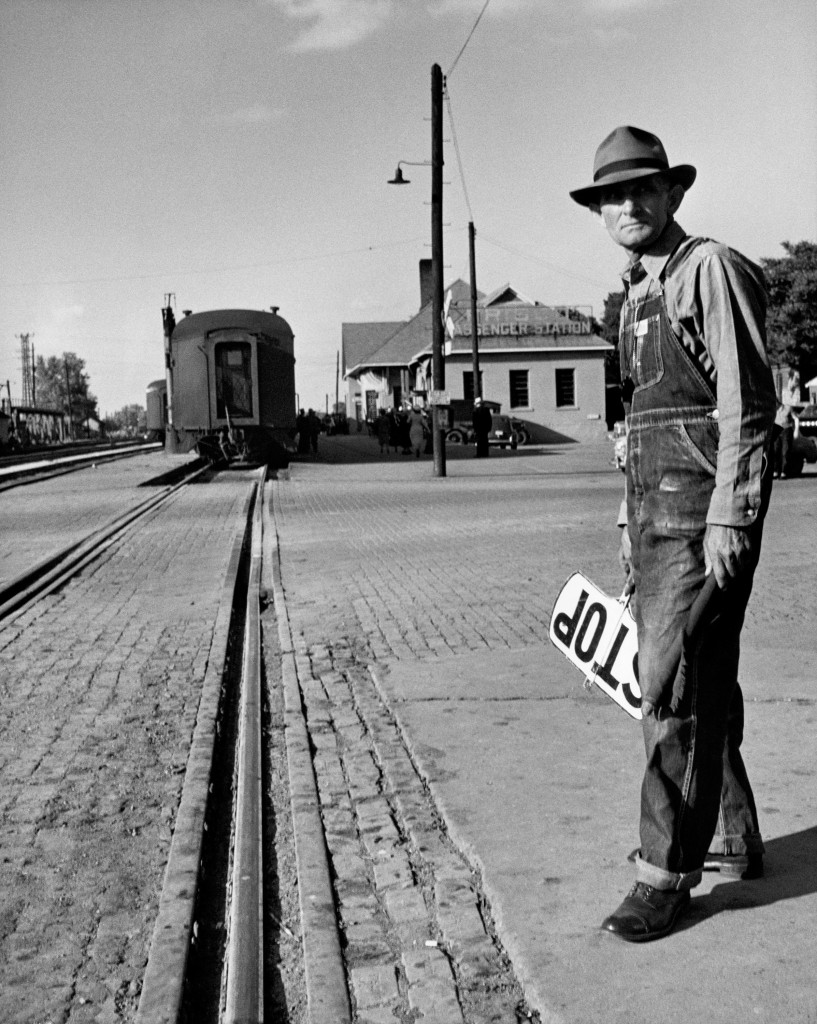

The very first photo in the exhibit shows that Parks was interested in making strong pictorial statements. It features a middle-aged white man in farmer overalls. He stands at a train crossing in the middle of town, a speculative look on his creased face as he surveys the photographer. The “STOP” sign held in his hand is a perfect metaphor for Fort Scott, Kansas and the South in the 1950s. The hard lines of segregation are as deeply embedded in mentality of this town as the steel railroad tracks running through the middle of town.

The photos on the four walls of the small gallery make what Parks has to say about his subjects crystal clear, even if you choose not to read a word of the background notes that accompany each print.

This is not to say that he was obvious. Parks was slyly political. He knew the power and stature of Life magazine and that white readers had little person-to-person interaction action with their black counterparts. He intended to present a nuanced portrait of “negro” life that had never been seen before in a popular national publication.

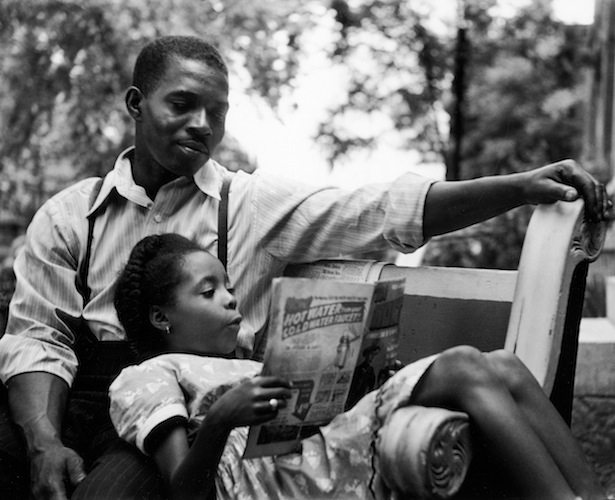

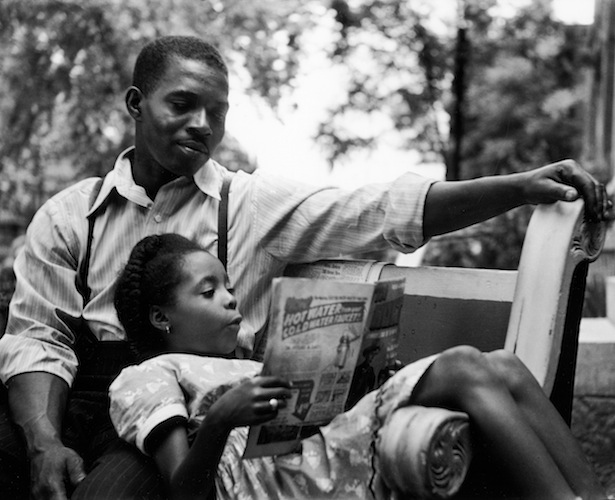

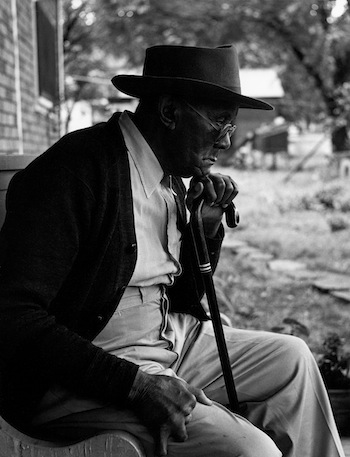

His photos of couples and families were taken with backgrounds of front doors, front porches or living rooms, all signs of stability. If you substituted white for black skin color, you you would have a documentary scrapbook review of white middle class America in the heartland. And that is the takeaway: We are in our own homes; we are husbands, wives, children, and elders; we have jobs; we enjoy leisure time; we are proud folks with middle class ideals; we dress well; we have aspirations; we are black. This is 1950, mind you. Life magazine was the photographic news magazine. It sold more than 13 million copies a week at one point in a 40-year span in which it dominated the market. The audience was affluent America…white America.

Following Life magazine protocol, Parks took notes about the jobs and wages of his subjects. Most of the photos are untitled, but are accompanied by the information gathered by the photographer.

Parks met and photographed Louella Russell, the only classmate still living in Fort Scott, and her husband and teenage daughter. He roamed the town, shooting photos of friends (including a few white residents), being reminded of the strict segregation of the day as he photographed a young black couple standing under the marquee of a segregated movie theater and a baseball game at a local park. Parks recalls sitting in the “buzzard’s roost” in the back upper reaches of the theater, the only place “negroes” were permitted to sit. His photo of a baseball game shows two black girls standing in what is the ‘colored’ section at the edge of the bleachers. As a bridge to connect with Life magazine’s white audience, he photographed some of the white workers in town.

The whereabouts of his other classmates corresponded with The Great Migration from the South and Parks hopped on trains to look them up in Kansas City, St. Louis, and Chicago. Parks reconnected with the white residents he remembered as young boys and girls. He’d been in a fist fight on the school playground with Lyle Myrick (leaning in doorway of his father’s garage) that ended up in a draw, a handshake, and a friendship. He found a disillusioned and dejected Mazel Morgan living in a Chicago tenement with her ill-tempered husband.

Did these photographs make a difference at the time? The irony is that they were not published. The photo essay and an accompanying article were slated to appear in the April 1951 issue of Life, but the project was discarded. The magazine’s explanation is that the outbreak of the Korean War and news of President Harry Truman’s firing of Douglas McArthur elbowed Parks’ photos aside.

Back To Fort Scott is not a dusty relic with no relevance for us today. Americans of all races are awash daily in media coverage of racial disturbances and violence. It seems as if a police shooting of a black man or boy is photographed and videotaped nearly every week. The dense coverage tends to make us feel as polarized and segregated, riven apart, as the races in Scott, Kansas in 1950. This potent little exhibition suggests that over sixty years ago some of the indispensable seeds of empathy had been sown.