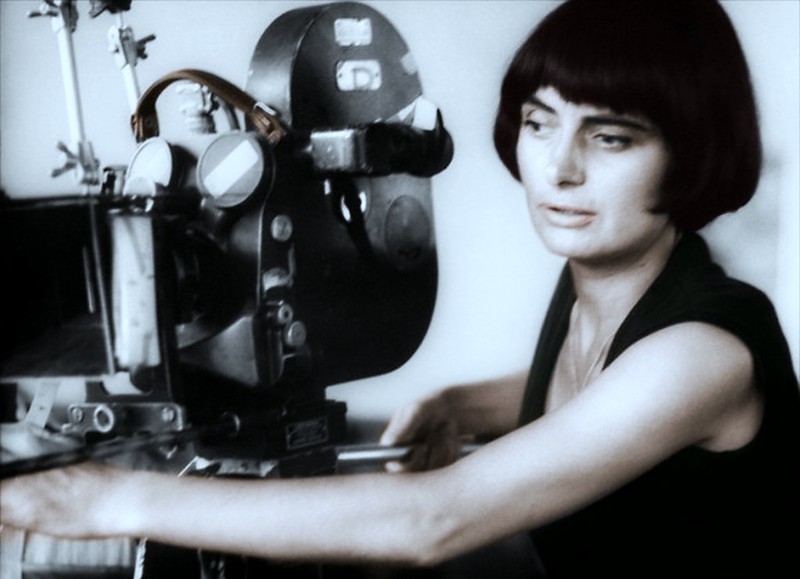

Agnes Varda: The Ardent Background

Always in the background of her films, landscape

as seeing

at times through a window.

framed by a curtain

held back by a hand. Landscape

as that hand

held up to the sunlight

showing through.

Or landscape of a hand

reaching out

to take a box of matches

off a shelf

that sees itself strike a match

to light a candle at noon.

Candle that sees

because a flame is a living thing.

Landscape as all

that is living in the eye in range.

Landscape as living

in the range of an eye.

The past doesn’t mean

so much to me because it’s always here.

Scene of silence

filling first the screen.

Scene of a hat

walking away.

Scene white with sun

until she is sitting on a wall

in a field

where the sun breaks down

because another sun

has come quietly in.

Bill Viola: The Reflecting Pool, 1977-79

The pool and the faces of dark. The pool and what moves across

and a man climbs out and walks off.

And a man walks through a forest uncommonly green, a man walks

up to the stone wall that forms one end

of the reflecting pool, walks through the yellow-green foliage, made so

by the dense green’s being fused with light

which lies across the top of the wall as he climbs up onto the wall and waits.

The yellow-green water with all the light on it

constantly changes or the reflection that is it

subtly evolves beneath the man who arcs out to leap in but remains

suspended against the background

of trees until he is inseparable from the leaves and we see

the reflections of unseen things.

Image: “Agnes Varda” by OFENA1, licensed under CC 2.0.

Cole Swensen:

These pieces are from an upcoming book, Art in Time, that reconsiders the genre of landscape art from a participatory and/or phenomenological point of view. In its traditional modes, the landscape genre has a well-earned reputation for appropriating, anthropomorphizing, and in other ways, creating rigid and delimited views of the “natural” world in order to support a fiction of our separateness from the that world that allows us to rationalize our domination, exploitation, and destruction of it. I put “natural” in scare quotes because the term is illusory and misleading; there is nothing that is not natural nor part of the natural world. The term natural as currently used simply perpetuates an us vs it fiction whose extreme result is ecological devastation and the concomitant climate change the planet is currently experiencing.

But not all landscape art supports those values; there are many artists in many genres whose works, explicitly or implicitly, recognize artist, viewer, and view as all part of a single, cooperative system. It’s a recognition that realigns responsibilities and calls for a renewed, vigorous attention to the world as one connected organism whose health is in grave danger at all levels. The works in this selection, and in the book as a whole, do not address these issues directly, but rather allow viewers to participate in, rather than just look at, the world, allowing them to experience that single, cooperative system for themselves, which amounts to a visceral argument that is much stronger than any verbal one could be.

Cole Swensen has published 17 volumes of poetry and a collection of critical essays, Noise That Stays Noise. A collection of hybrid poem-essays, Art in Time, from which this piece is taken, will be coming out from Nightboat Books in 2021. Most of her work is related to the visual arts and often addresses landscape and land-use concerns. A former Guggenheim fellow, she has been a finalist twice for the LA Times Book Award and once for the National Book Award and has been awarded the Iowa Poetry Prize, the SF State Poetry Center Book Award, and the National Poetry Series. She also translates poetry, prose, and art criticism from French and won the 2004 PEN USA Award in Literary Translation. She divides her time between Paris and Providence RI, where she teaches at Brown University.

Latest posts by Cole Swensen

(see all)