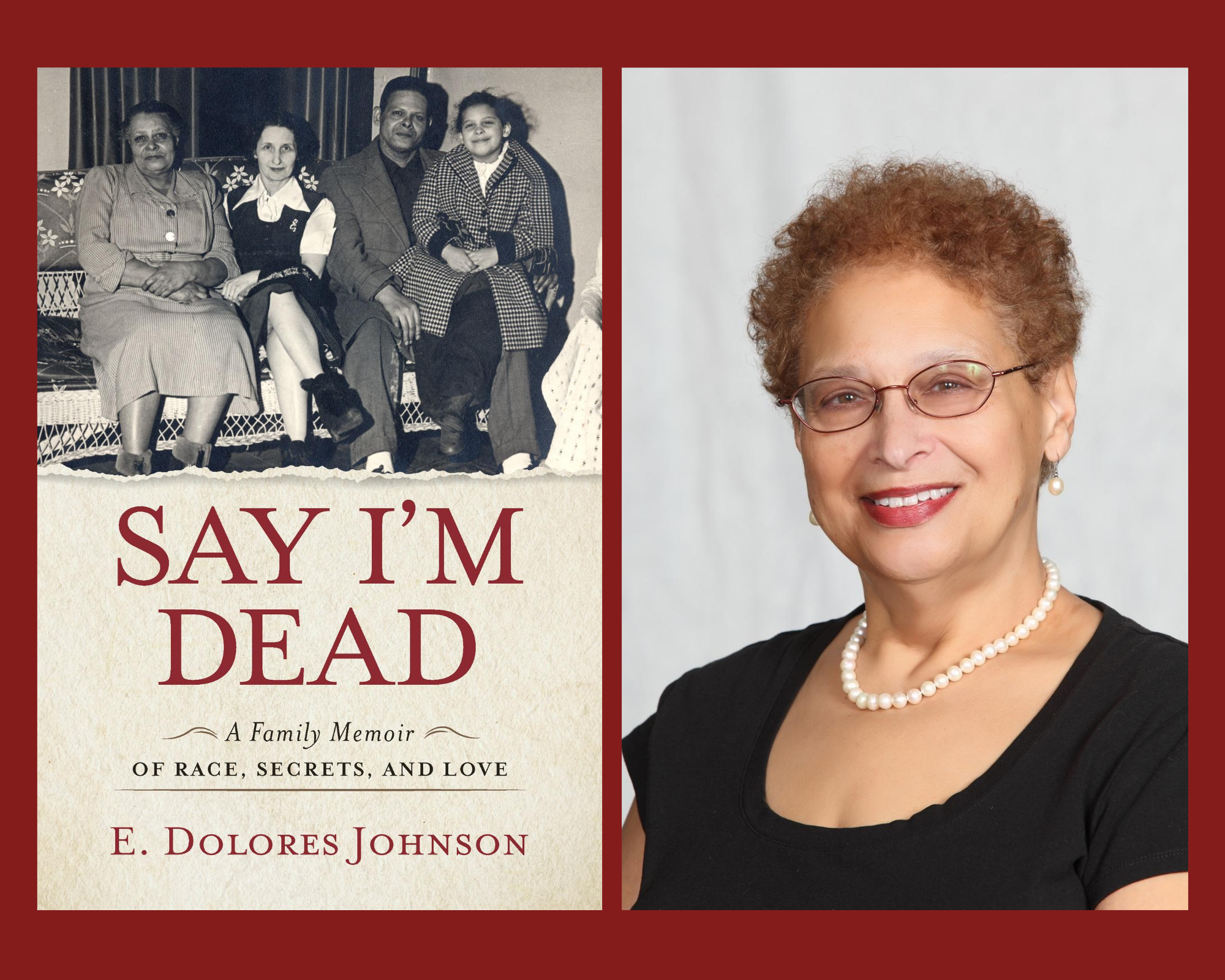

Pangyrus Nonfiction Editor Artress Bethany White interviewed E. Dolores Johnson, author of Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets, and Love (Lawrence Hill Books, 2020) to learn more about her memoir and the tragedy of racism in her family history.

Artress Bethany White: Let me start by saying that I really enjoyed reading Say I’m Dead. In your memoir, as you worked through themes of lynching, economic oppression, and racial discrimination—themes that pervade the African American literary tradition—what kept you feeling that your story was worthy of being told amid so many others?

E. Dolores Johnson: The themes of lynching, economics and discrimination are the truth of my family and Black life in America and are vividly portrayed in scene after true scene of Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets and Love. The book also deals with the related theme of racism levied against interracial families. In my family, we lived with both kinds of racism, because we have five generations who lived in mixed-race relationships. And that is the uniqueness of this story, that and the portions told from my white mother’s point of view differentiate Say I’m Dead from so many other books in the canon.

The part of this memoir that people gravitate to is the escape of my white mother and Black father from the 1943 Indiana Klan culture to marry legally elsewhere and hide from Mama’s family for 36 years. Yet the beginning of my family’s mixed relationships, as in all such relationships in America, began in slavery. In the 1800s, my 15-year-old great grandmother was repeatedly raped by a white man on a plantation. I believe Say I’m Dead is a narrative worthy of being told because it stands on the truth of racism yet has a hopeful note when decades later the puzzle pieces of the two sides of my family, and the two sides of myself, come closer together through love. By the two thousand-teens, my Black daughter did what her grandmother never could: marry across the race line without fear. And now my mixed-race grandson is part of census statistics: the growth in mixed-race births outstrips the birth rate for single race babies three-to-one. Yet he must be trained on the racist dangers he will face in America and his role in defeating them. This is, therefore, not the oft-told tragic mulatto story either.

ABW: In your memoir, you poignantly recount being told that college was not for you by your white high school guidance counselor. Thankfully, you were offered and able to accept a full scholarship to Howard University and went on to earn a Harvard MBA. Under your guidance, your daughter attended both Brown University and Princeton. Do you believe that African American students continue to face a level of educational discrimination in this country similar to what you faced in the 1960s?

EDJ: Only through the serendipity of a neighbor telling me to take the scholarship exam for Howard University did I get a college education. Until then, higher education was a closed door to me, a girl whose guidance counselor never looked at her transcript of honors classes, yet said Black girls “don’t go to college.” Hers was a racism that directed me to take up other women’s hems for a living, even though I’d botch every one of them since I got a D in sewing. Winning that four-year, fully paid Howard scholarship changed my life. There, not only was I educated in economics, but the history and issues of Black America. It was the place that gave me the intellectual foundation and personal confidence to go on to Harvard and an executive career. It was the drive for educational success passed on to my daughter. Unfortunately, my experience with that counselor in Say I’m Dead has been similarly recounted by many others. In Becoming, Michelle Obama’s 1980s counselor tells her she is not Princeton material, so shouldn’t apply. And yes, this discouragement continues today, according to a 2017 article in Education Next, where Johns Hopkins reported that “… white teachers, who comprise the vast majority of American educators have far lower expectations for Black students than they do for similarly situated white students.”

ABW: One of my favorite and most compelling sections of your memoir is when you transition from your husband’s illness in the aftermath of the cross-burning incident in your front yard in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in the mid-1970s to the childhood event of your parents purchasing their first home in Buffalo, New York. You write deliberately about redlining and the exploitation of Black homeowners. Recently, I found myself considering that home ownership in all-white neighborhoods is proof of the performative nature of liberal white allyship separating political discourse from praxis. I am curious about your thoughts on this assessment considering the experiences of you and your family.

EDJ: My family was devastated by the destruction of the beautiful parkway that attracted us to buy in that certain neighborhood across town from our ghetto. The parkway was replaced within a few years of our arrival by an Expressway. It accommodated the white flight people who didn’t want to live near us, moved to suburbs, and then had long commutes that inched through rush hour. In Say I’m Dead, this disregard of our newly achieved homeownership was but one way that whites maintained de facto segregation across America. The cross burning at my newly purchased Baton Rouge home was another.

Sadly, America’s housing remains segregated. Ninety percent of suburban residents are white while many urban areas are majority minority. To my mind, that is a cornerstone of racism’s continuing life. Segregated housing means segregated schools, which means different races have little opportunity to know each other and form relationships that can overthrow underlying stereotypes, fear and doubt.

Once established in my career, I chose to live in white suburbs for two reasons: better schools for my child and rising property values. One of my white neighbors expressed surprise at my economic and educational standing among them, which signaled a lack of understanding of Black success. We all got along. But when HUD proposed affordable housing in that town, people fought it, not understanding the motive to make teachers and first responders able to afford to live there. As to allyship, the question is not whether some whites have the intention of learning about racism, but what are they willing to give up to eradicate some of it.

ABW: In the latter third of your memoir, you compare the lives of your white ancestors to that of your African American forebears. You note that, “My maternal grandmother was raised by a striving craftsman who chose to immigrate to America for a better life, plying his trade freely in the late 1800s while my Black sharecropper great grandmother was being raped by a plantation white man.” You use these situational and economic realities to graphically depict the historical economic inequity between white and Black Americans. How do you see an acknowledgement of this history ending “opportunity privilege” in this country?

EDJ: Thanks for calling out that passage. I wanted readers to understand the root of today’s inequities, back to that real 1800s difference in my own family. Those who have read that section of Say I’m Dead have yet to comment on it. Feedback thus far has been an overall condemnation of the racism my family experienced, but I’m afraid acknowledgement of racial inequities will not end “opportunity privilege!” At this current moment of racial reckoning, America is only beginning to know the history and impact of inequities. Knowing precedes acknowledging, which precedes actions that can change the status quo.

ABW: As I read your book, I thought about my own literary journey to discover more about my family’s American enslavement and white genealogical ancestry. When I tested my DNA, I ended up being of 28% European ancestry, yet for me to claim myself as a white citizen would be ludicrous on multiple levels, starting with the fact that I am a brown-skinned woman. When you carried out your own DNA test, you tested 75% European ancestry. Do you attribute your grounding in your African American selfhood as a combination of a more realistic acceptance in the Black community of a history of enslavement leading to a logically diverse color palette as well as a devotion to your more brown-skinned father and his race experiences in America?

EDJ: Throughout American history, people mixed with Black and white have been considered Black. That started with slavery too, when Massa fathered mixed offspring; he counted them as additions to his slave holdings, not family. Hence the Black community is still where mixed people are included and comfortable, rather than white ones. Though DNA says I am 75% white, I, like in Caroline Randall Williams’s New York Times article, “…am a confederate monument.” What tips my DNA into mostly white is my great grandfather, the plantation rapist, whose blood repulses me. What has formed my dominant identity is both the racism my family and I endured and my four years at Howard University where Black pride, achievement and activism took root in my purpose.

ABW: Once you understood that your parents’ marriage was a secret one, your memoir becomes largely about finding your white relatives as a means of coming to a better understanding of your biracial identity. Was it your desire that readers walk away from reading about your journey with a surety that embracing difference carries fewer pitfalls than holding onto traditionalist racial baggage?

EDJ: After learning so much by tracing my father’s genealogy, I felt the hole in me from not knowing anything about my mother’s half of my heritage. The idea of biracialism wasn’t on the table in 1979 when I searched for them because there was no permission to be half white in America. There was no telling what reaction her family would have when I showed up. The beauty of my story is that the fear, secrets and separation my parents lived with because of systemic racism did not hold up on the personal level when we found Mama’s white family. So, I embraced my white family, my half who decided love trumps race. Say I’m Dead shows America can bring the races together, though I cannot assure you of how that will happen or what the price of getting there will be.

____________

E. Dolores Johnson is the author of Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets, and Love (Lawrence Hill Books, 2020), a multigenerational memoir that shows America’s changing attitudes toward mixed race through the courageous journeys of the women in her family. Dolores was born in Buffalo, NY. She earned degrees from Howard University and Harvard Graduate School of Business in Boston. Johnson is a published essayist focused on inter-racialism. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. To learn more about her and her work, visit her website www.edoloresjohnson.com or follow her on Twitter @e_dolores_J, Instagram @edoloresjohnson and FB Dolores Johnson.

- Race, Family, and Enduring Histories: An Interview with E. Dolores Johnson about her Memoir Say I’m Dead - September 12, 2020

- Outlander Blues - June 14, 2020