In July of 1953, at a glittering party thrown by Truman Capote in Portofino, Italy, Tennessee Williams and his longtime lover Frank Merlo meet Anja Blomgren, a mysteriously taciturn young Swedish beauty and aspiring actress. Their encounter will go on to alter the rest of their lives. In this beautifully written novel, Christopher Castellani explores what it means to love a powerful public figure like Tenn and to go on in life without him.

Virginia Pye: Many readers will be drawn to your novel because of your portrayal of Tennessee Williams, who is such an intriguing literary figure. But I’m curious to ask about Frank Merlo, Williams’ partner in 1953 Italy, where the majority of your story takes place. Merlo could hardly have been more different from Williams, and yet they were happy for a time and, while together, Williams created his best work. Can you talk about what drew you to explore not just a great literary figure, but the unknown man who inspired him?

Christopher Castellani: You’re right that Williams gets only a supporting role in this novel; Frank is the narrator of their sections, and we see Williams only through his eyes. I knew from the earliest drafts Williams couldn’t be a point-of-view character, primarily because I had nothing new or insightful to add to the existing literary and biographical scholarship, in particular to John Lahr’s excellent recent biography, Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh. I was much more interested in what it was like to be the partner of such a mercurial genius, especially after I learned that Frank was, like me, a working-class first-generation Italian-American guy from the mid-Atlantic region of the country, and that the fifteen-year period in which they were together was the most artistically and commercially successful of Williams’s career. My primary interest was the power dynamics between the two men, how they defined their relationship in a time long before same-sex marriage was a possibility, and the toll their stormy years together took on Frank’s sense of self. It’s worth mentioning that Frank was far from “unknown;” his official role – for which he drew a salary – was as Williams’s secretary, but they traveled quite openly through the rarified set of the 50s glitterati and traveled together all over the world. Williams gifted Frank a percentage of the profits of The Rose Tattoo – the only play of his that Frank directly inspired – in perpetuity, which didn’t turn out to be very long for Frank, who died at forty of lung cancer. One of the reasons I chose to set most of Leading Men in Italy rather than Key West or Manhattan, where they also lived, was that Italy was the place they were happiest together, and I wanted to bring Frank back there for a while at least.

VP: Did you find yourself falling for Frank, as Tennessee must have? Or rooting for him, in the face of Tennessee’s growing indifference? I know I did. The final scenes of Frank’s life are heartbreaking because of Tennessee’s absence. I wondered if what first grabbed you about their story was how Frank’s true-life tale echoes Williams’ own staged tragedies?

CC: I fell head-over-heels for Frank the first moment I encountered him, which was in Dotson Rader’s memoir of Wiliams, Cry of the Heart, where Rader poignantly described his last days wasting away in a hospital bed. By all accounts – letters, biographies, William’s own Memoirs – Frank was unfailingly good-hearted, always game for a party, loyal, reliable, an avid reader and opera buff, an aspiring dancer and actor, and had effortless charm in direct proportion to his good looks. Williams called him “The Little Horse” because of his short stature and tight wrestler’s frame. What’s not to love? And yes, I sensed immediately, upon reading more about their life together – the longings and miscommunications, the frequent betrayals on both sides, the inability to fully articulate what they meant to each other, the harboring of secrets – that they were living out a drama worthy of Williams’s most enduring literary efforts.

VP: I found Frank to be more sympathetic than Tennessee, and yet Tenn is the sun around which the planets of his friends revolve. In your novel, Frank describes it this way: “Tenn had a life force that kept the words coming and the blood flowing, that got him out of the tunnel and the actors onto the stage and the audience to their feet. If you didn’t have your own life force, no one could lend you his. No one could save you.” It seems that the most vivid time in Frank’s life, or perhaps in any life, is when in the presence of such genius. Can you say more about Tenn’s force and Frank’s way of dealing with it, and what we can learn from it?

CC: I think one of the things that made their relationship so interesting is that they both had that strong life force, that push for more and more and more of life, but that they had different ambitions which were often at odds. The life force Frank describes in the passage above is specifically related to Williams’s literary ambition and his work ethic, his compulsion to make things. Williams was obsessive about work and routinely put in the hours to write in multiple genres; Frank seemed to be obsessive about taking care of Tenn, of making sure he had a time and a place and a clear enough head to work, but perhaps Frank was just as obsessive about their social engagements, their friends, their travel, and their sex lives, which were voracious. What I was trying to get at in that passage is that Frank didn’t have nearly the artistic ambition that Williams did, but that he longed for something like it – something deep and sustaining – that might give him a more rightful and stable place in Williams’s world. Frank was something of a dilettante, which is a less-generous way of saying he had many artistic and aesthetic enthusiasms without the talent or commitment to make something out of them. A big factor in the power dynamics between them – at least in my psychological read – is that Frank worried that Williams didn’t respect him as anything but a secretary.

VP: Did you feel a heavier weight of authenticity when writing about real historical figures and not characters who are wholly invented? In other words, did your research for Leading Men constrain your imagination or fire it up?

CC: The dirty little secret about writing about real historical figures – and about writing historical fiction in general – is that, for me at least, it’s much easier than making things up from whole cloth. Much of the work is done before I’ve even opened my notebook: I know what the characters look like, where they lived and died, the plot arc of their lives. My job as a writer is to give these characters’ stories shape and meaning, to contour them, to fill in the cracks between what is “known” about them, to give them an inner life. I find this an exciting artistic challenge, and I find that working within the constraints actually turbo-charges my imagination. The Frank Merlo and Tennessee Williams and Luchino Visconti and Anna Magnani in Leading Men bear some resemblance to the versions of them that exist in biographies, but at their core they are only my interpretations formed from that alchemy of research and imagination. I love how Margaret Atwood put it: “We read historical fiction for the same reason we keep watching Hamlet: it’s not what, it’s how.”

VP: I write literary novels set in historic eras but never thought of them as “historical fiction.” I think that term has evolved as a way to market books. Do you think it matters when a story is set, in terms of how you approach it as a writer?

CC: I honestly never thought of myself as a writer of historical fiction until my first book came out and, because it was set in Italy in World War II, it was suddenly categorized as such. I think the term is useful in marketing – there are some readers out there who won’t read anything set after 1900, apparently! — but that it’s not particularly useful when it comes to how we approach the craft of a literary story or novel. You have to do the same work to create a setting and context and atmosphere in a book set in contemporary Boston as you do in a book set in the same city a hundred years ago. There are conventions of the genre you must consider if you’re writing more commercial historical fiction, but I don’t think those apply to efforts like ours, which are much more concerned with the insights we can draw from inner workings of characters and their interpersonal dynamics.

VP: If you don’t mind sharing, what are you working on now?

CC: I am slowly, and in alternately exhilarating and dispiriting fits and starts, trying to find my way into a new novel. I wish I could tell you what it’s about, but I honestly don’t know yet. Unlike with Leading Men, I don’t have a character like Frank Merlo about whom I am absolutely certain I want to write. I miss that certainty and that direction – that utter devotion to a subject – which is, I guess, another way of saying that I miss Frank.

—-

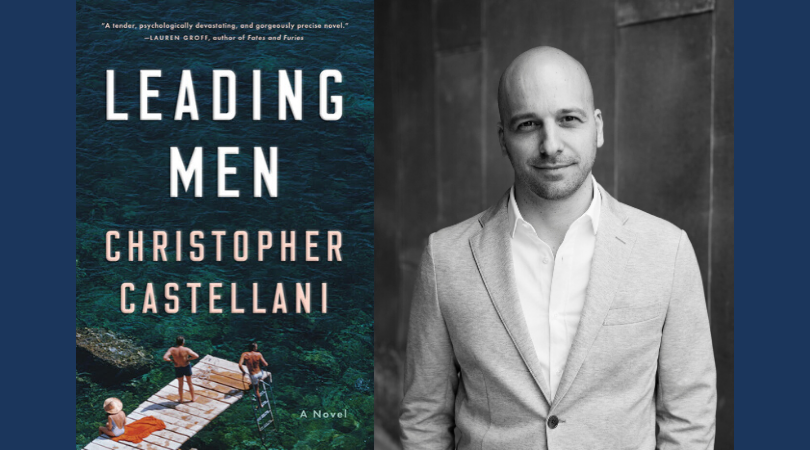

Christopher Castellani is the son of Italian immigrants and a native of Wilmington, Delaware. He currently lives in Boston, where he is the artistic director of Grub Street, the country’s largest and leading independent creative writing center. He is the author of three critically acclaimed novels. His newest is Leading Men, for which he received Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the MacDowell Colony, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Leading Men was published in February 2019 by Viking Penguin.

- An Interview with Christopher Castellani about his novel Leading Men - June 28, 2020

- Marjan Kamali - May 16, 2019