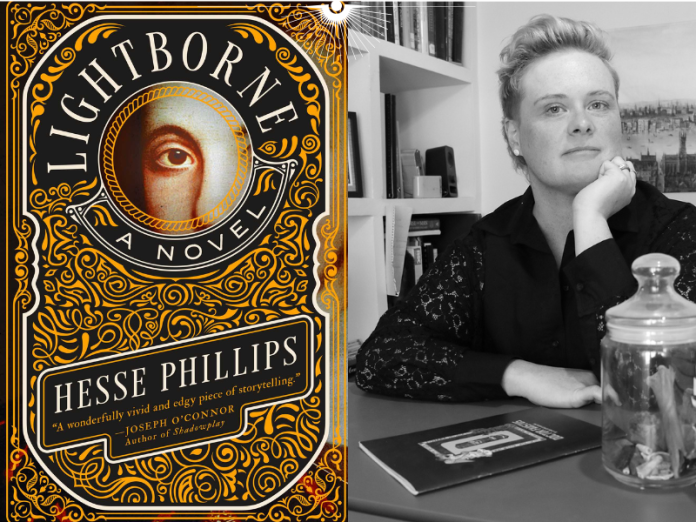

On Queer Ancestors, Stubbornness, and Living “Close to the Knives”: A conversation with Hesse Phillips’ about their debut novel, Lightborne

Famed poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe has, over the course of his short life, become a roaring success, but by the spring of 1593, the Elizabethan court is filled with paranoia and Marlowe has been arrested on charges of treason, heresy, and sodomy. With the queen’s spies closing in, Marlowe meets a stranger who is obsessed with his plays, and who will, within ten days’ time, first become Marlowe’s lover — and then his killer. In this richly atmospheric and beautifully imagined novel, Hesse Phillips brings Marlowe’s final days to life in vivid, gripping detail. This interview was conducted by Pangyrus Associate Fiction/Fiction Features Editor Whitney Scharer.

Whitney Scharer: Your novel, Lightborne, is such a fascinating look at one of England’s most well-known literary figures. What was the spark that first got you interested in Christopher Marlowe? How did that early excitement grow into this novel?

Hesse Phillips: I have this incredibly clear memory of the first time I ever encountered Christopher Marlowe: it starts with me, maybe fourteen years old, finding a copy of Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus in amongst my father’s books, and it ends with my father telling me everything he could remember having learned about Marlowe in some long-ago college English class. I don’t really know if it was then or sometime later that I learned about how Marlowe was accused of heresy, treason, and sodomy; or how Marlowe allegedly made incendiary comments about the Virgin Mary’s virtue, Jesus and John the Baptist’s suspiciously close relationship, and of course his famous quip, “All they that love not tobacco and boys are fools.” But the thing I remember most about Marlowe’s story was that the more I learned about him, the more I had this strange sense that I was meeting someone with whom I shared a past, or even a blood relation. In fact, it was just my first time hearing about a queer person who had existed prior to my lifetime. Nowadays, I often refer to Marlowe as my first “queer ancestor.”

I remained quietly fascinated with Marlowe right up until college, when the fascination exploded into outright obsession. Reading Marlowe’s play Edward II was what sent me over the edge — the first English play to ever feature an explicitly queer, romantic relationship between men. I ended up writing my undergrad thesis on Edward II, and simultaneously began tinkering around with a novel about Marlowe on the side. In fact, the title Lightborne is the name of one of the most infamous characters in Edward II — the murderer who kills the titular king in a truly horrifying parody of gay sex.

WS: So this has been a true passion project for you, hasn’t it? I love that you refer to Marlowe as your first queer ancestor, and you’ve obviously done your research — you wrote a thesis about one of his plays! But the kind of research needed for writing a novel is a little different, I think, than academic research, and novels about real people — especially people as well-known and studied as Marlowe — also take the additional chutzpah of putting fictional words into people’s mouths. When I was writing my own historical novel, I developed a rubric for myself so that I could make decisions about when it was okay to dramatize the past and how I could fit that dramatization into the historical record. How did you approach this challenge?

HP: Oh, very cautiously at first, and then less cautiously as time went on! The fun and sometimes daunting thing about working in the early modern period is that often you’re working with just the bare skeleton of a story — or a person, for that matter. The Elizabethans were scrupulous record-keepers and extremely litigious, so we have a wealth of historical documents that can tell us about incidents within someone’s life, but often few to no materials that can tell us anything about what was going on between those spikes of activity. Marlowe lived life “close to the knives,” as it were, so we know a lot about things that happened to him or around him because he was often in trouble with the authorities. But as to who Marlowe was, or what motivated him, how exactly he might have sounded in an everyday conversation, exactly what he did in fact believe about himself or the world, or even what he looked like — none of that is 100% clear. It’s those things that I tended to have the most fun exploring in scene, trying to reverse-engineer this whole person out of a collection of court records and poetry.

And you’d think having access to Marlowe’s poems and plays would make him easy to put on the page, but if anything all the differing scholarly interpretations just make it extra complicated. One particular version of Marlowe that emerged in the 1950s and has sort of taken over popular perceptions of him is this idea that he was some ruthless, larger-than-life megalomaniac, with no real evidence to back up the idea other than the fact that he often wrote about those very sorts of people. I always hated this view, because I find it both oversimplifies what Marlowe was doing as a dramatist and deprives him, personally, of humanity and depth.

So, I tried to go in the exact opposite direction with my characterization of Marlowe, portraying him as someone who is deeply conflicted about the casual violence and cruelty of the world around him, who uses his infamously gory plays to satirize and expose the hypocrisy of his so-called betters. He’s not really the kind of person who aspires to be a revolutionary — he’s much too private for that — but he has that fatal combination of a deep-rooted sense of justice, hatred of authority, and trouble keeping his mouth shut. It’s this that puts him on the wrong side of the dogmatic Elizabethan state.

WS: Creating complex psychological portraits out of the facts in the historical record is one of the biggest challenges of writing historical fiction, but there’s also the setting and all the other details needed to make the world of the novel come alive. If I were writing about Elizabethan England, I feel like every single detail would stop me in my tracks (“What did their bed frames look like? Were the pillowcases linen?,” etc.). How did you make that world come fully alive, while also making it accessible to modern readers?

HP: I’m sure you can relate to this: it’s all about that struggle to decide what details really serve the story. When I think back to earlier drafts, they were chock-full of descriptions that boiled down to, “LOOK AT ALL THE RESEARCH I DID” but didn’t do anything to move the story forward or deepen the reader’s understanding of the world. I’d be in mid-flow of a sentence when, yeah, I’d realize I didn’t have the faintest idea what your bog-standard Tudor bed frame looked like, and I’d fall down research rabbit-holes trying to find out… only to later realize that the information derailed the scene as read just as much as it had derailed me in writing it.

In the end, I found the best way to decide which historical details are actually worth including was to ask myself whether they A) had some sensorial presence in the scene, as a thing the characters touched, smelled, tripped over, or otherwise interacted with; or B) would do so in the future, at a point when I wanted the reader to remember this particular scene again; or C) served a thematic or psychological purpose in revealing character, foreshadowing an event, or calling the reader’s attention to some force looming in the background that’s going to have an impact on the story. A loose rubric, maybe, because the physical and psychological/thematic worlds are so intertwined. Really, I think the best material details in a scene should accomplish all of the above, though of course not everything needs to.

WS: I know from your blog posts that it took you a long time — over twenty years! — to write this book. As a slow writer with a penchant for perfectionism myself, I find this inspiring, and I know that many of our readers will also be interested in learning about your process. Tell me a bit about how the finished draft of this novel came to be.

HP: Yup, twenty years — that’s just about half the time I’ve been alive. The short answer is, I’m crazy and I find it nearly impossible to let go of things. The long answer is, I wrote not just one, but multiple books about this same subject over those twenty years. It took more false starts than I can really remember to get to Lightborne as it stands now, sometimes because life got in the way, but in many cases because of sheer stubbornness. Rather than just accept that some overly-ambitious concept or structure was not working and try something else, I’d spend months and years desperately trying to make certain ideas work that were really just holding me back. At one point, Lightborne took place in three different time periods and had three different sets of protagonists. At another, the whole thing was told from the point-of-view of Marlowe’s ghost!

Stubbornness is my Achilles’ heel, but ironically, it was Lightborne’s saving grace in the end. As much as I clung to narrative dead-ends over the years, I also clung to my determination to finally, finally write a book that worked, and then to sell that book. Really, I think it took twenty years for me to figure out what things I should and should not be stubborn about — because it was only after I gave up on many of my initial grand designs that the book finally came alive.

I do work quite deliberately, which probably also contributed to that long time frame. My favorite metaphor is that I write like the tide coming in, in waves that move a little further up the beach each time, but always start from somewhere far out to sea. I’ll draft a book in linear stages, each with its own multiple revisions, before ever reaching the end… and then throw it all out and start over again!

WS: Pangyrus was lucky enough to publish a fabulous story by you, “Sebastian Melmoth in Silver City,” in 2023. It’s not a novel excerpt, but it’s thematically related to the novel. How did that story come to you? Do you find writing short fiction helpful to your novel-writing process?

HP: I’m still so thrilled that Pangyrus accepted that story. I’d been trying to get into Pangyrus off and on for years, and that one finally did it! “Sebastian Melmoth in Silver City” is about a fictional leg of Oscar Wilde’s North American tour where he visits a remote mining town in Idaho and inadvertently inspires a violent act. He’s accompanied on this tour by Claude Sarony, a photographer working at the vanguard of his craft, whose photos of Oscar’s visit to in Silver City haunt him throughout his life. The place where this story and Lightborne intersect is quite personal, really — like Marlowe, Oscar Wilde was another one of my “queer ancestors,” with whom I was downright infatuated for many years, to the point where I think it became slightly detrimental to developing my own worldview, haha. I think “Sebastian Melmoth” grew out of my later disaffection with Wilde’s rapacious materialism, his flashes of callousness, and his rather insufferable self-absorption, to name a few of his defects. Despite all this, I still need Wilde, the simple fact of his existence having been so important to both my shared history with other queer people and my own personal history. He’s a bit like this deeply complicated, inaccessible, but nevertheless beloved father-figure to me, which is sort of what he becomes for Claude in the story.

I have to confess, I very rarely write short stories. They nearly always come like a bolt from the blue, get drafted in a frenzy of intense concentration, and are then frequently abandoned once that initial burst of energy subsides. “Sebastian Melmoth” was one of those rare cases where I kept working on it, because I knew I had unfinished business with Wilde and could feel I was so close to finally resolving it. That, too, ties it to Lightborne, if only because I think part of what motivated me to finish Lightborne was that feeling of unresolved business, like a ghost I had to put to rest.

WS: I’m not going to ask you what you’re working on now — you have a book coming out on October 22nd! If I were you, I wouldn’t be working on anything! — but I’d love to know what you’re reading. Has there been anything you’ve read recently that you’ve truly loved?

HP: Oh my God, how many pages am I allowed? For one, I’m completely engulfed by the writing of Julia Armfield, having started with her short story collection Salt Slow, moved on to her debut novel Our Wives Under the Sea, and am now deep into her follow-up, Private Rites. You can’t call her work “horror,” exactly, as it’s so much more than that, though she has this uncanny fluency with the horrifying. It’s “tell the truth, but tell it slant” in the way your vision would go slant if your left eye suddenly slid down your cheek!

Probably one of the most exciting books I’ve read recently just in terms of sheer gumption is Justin Torres’ Blackouts, which completely reimagines what a novel can be. Combining blackout poetry, historical documents both real and imagined, photographs, memoir, and fictional narrative, it manages to create this notion of the novel as archive, which is just totally my jam. The Irish writer Joseph O’Connor does this too, brilliantly, and if I can recommend one of his that’s perfect for spooky season, it would be Shadowplay — a delectably fun take on Dracula as told through the complicated friendship between Bram Stoker and the actors Henry Irving and Ellen Terry.

Believe it or not I am working on book number two, in fits and starts! I suppose I shouldn’t say too much in, y’know, indelible print, but it will move deeper into some of the backstory of Lightborne, and concerns an isolated country estate, three women accused of demonic possession, and a Catholic plot to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I!

WS: Sounds fantastic, Hesse. I can’t wait to read it! Thanks so much for taking the time out of your busy schedule for our conversation.

***

Lightborne was published in the UK in May 2024, and is forthcoming in the United States from Pegasus Books (available October 22nd). Hesse Phillips will be on tour at the end of the month. Boston locals can catch them at Trident bookstore on October 22nd, where they’ll be reading as part of the Craft on Draft series, or at Porter Square Books on October 23rd, where they’ll be in conversation with Michelle Hoover.

Hesse Phillips (they) was raised in rural Pennsylvania but now lives in Spain. Much of their early life was spent in the theater, where they developed a love for Shakespeare and the other Elizabethan/Jacobean dramatists. They earned a BA in theater history at Marlboro College, Vermont, and later a PhD in drama from Tufts University in Boston. While writing their undergraduate thesis on Edward II, they also began working on a novel about Christopher Marlowe that would eventually become Lightborne. They are a proud graduate of GrubStreet Boston’s acclaimed Novel Incubator.

- An Interview with Hesse Phillips, Author of Lightborne - October 19, 2024

Great interview! Cannot wait to get my hands on Lightborne.