There’s much to say about George Michael: pop superstar, sex symbol, earworm-making musician, mega-talented vocalist, closeted gay man, addict. In James Gavin’s new biography of the Brit, George Michael: A Life (Abrams Press, 2022), these labels get unpacked with a vigor and obsession that marks it as arguably the most probing, expansive look at Michael’s life.

Drawing from a wealth of material and interviews, the book treads well-worn ground about Michael’s meteoric rise to fame in the eighties as one-half of the British boy band Wham! But Gavin, whose prior biographies focused on Peggy Lee and Lena Horne, also breaks new ground that perhaps Michael wouldn’t have condoned.

Gavin takes a hard look at the traditional Greek Orthodox family Michael was born into, noting that, “Almost everything to do with [Michael], from his gut ambition to his sometimes crippling insecurities, in some way pointed back to his father.” Gavin also examines how Michael’s very public outing in 1998 stripped him of the option to play coy about his sexuality, as he’d done for nearly two decades, causing the singer great pain. Perhaps the freshest aspect of Gavin’s work is the presentation of the closet that Michael stayed in for so long, calling into question how his life may have been different if he’d not enjoyed his greatest commercial success at a time when the world was not ready to embrace an openly gay pop star.

***

Growing up in suburban Boston in the eighties, a shy, closeted child myself, I have scant memories of George Michael beyond flashes of the pastel and white he and his Wham! bandmate, Andrew Ridgeley, wore in videos for worldwide hits like “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go.” When Michael went solo, he transformed into the hyper-masculine version of himself he created for his most successful album, Faith, complete with leather jacket, aviator glasses and blue jeans. He didn’t register in my young, gay brain as anything but a straight man singing to women, just as the George of that time likely wanted.

Gavin convincingly plots out Faith’s carefully calculated success. By appealing to a fan base that wanted to see him as straight and masculine, Michael made Faith the number one album in America in 1988, but he never achieved similar commercial success again. His discomfort with this image led him to go so far as to torch the leather jacket he’d worn in the “Faith” video and remove himself altogether from the video for “Freedom! ‘90,” its cries of freedom my first inklings, as a 15-year old boy at the time, that this megastar and I had something in common.

When I enrolled at Oberlin College in 1998, I’d already been out for five years. In April of that same year, Michael was publicly outed after his arrest for public lewdness for exposing himself to an undercover police officer in a Beverly Hills park bathroom. Looking to unite my interests in research, pop music, and sexuality, I turned to Michael with fresh eyes — trying to understand how this once most bankable star, as commercially successful as Madonna or Prince, spoke to Queer identity now that he’d been pushed out of the closet. Surely I wasn’t the only gay kid who’d thrown his hands in the air to the refrain of “Freedom! ’90” and felt seen.

As I interviewed my peers at Oberlin (as part of an LGBT research grant awarded by the English department) — two years after Michael was arrested and released his song “Outside,” which addressed the alleged police entrapment that led to his outing — I found I’d not been alone in my response to Michael’s music. Each Queer student I spoke with recognized something in Michael that lined up with their Queerness, even if Michael hadn’t been upfront about his sexuality.

The more I, a curious college student and singer, listened to Michael’s recordings, the more I recognized — as millions of others had, and as Gavin highlights throughout A Life— that regardless of the closet he spent most of his peak commercial years in, the man could sing. As I began to explore what I could do with my own voice, I listened to the powerhouse vocals of “Careless Whisper” and “One More Try,” wondering at the melancholic tone behind the latter’s phrase, “I don’t want to learn to hold you, touch you, think that you’re mine.” Michael, Gavin explains, wrote “One More Try” for an unrequited male love, although the song was released during his Faith years.

As I heard my peers’ recognition of Michael’s sexuality, even when he’d been closeted, I also heard their frustrations that he’d not been more open at his peak. We imagined what it might have done for Queer kids like us if he had. I wondered, too, as Gavin does, what price he’d have paid in fans and dollars lost, if he’d come out earlier.

***

A Life provides a novel excavation of the years following Michael’s outing. It addresses how his music changed as he began to openly sing to male lovers, and about homophobia and AIDS — which claimed the life of Michael’s first and, according to Gavin, most emotionally important boyfriend, Anselmo Fellepa. Despite Michael’s lyrics after 1998 being ripe with Queer identity, his legacy as an artist who’d pandered to heterosexual norms made him a difficult individual for many of the Queers I interviewed to embrace as one of their own.

Gavin contextualizes this, quoting the gay gossip columnist Billy Masters: “When I meet gay artists now, they’ve been out since they were ten… [t]hey didn’t have to go through any transition of private versus public life. Even when George was totally open he was still a product of where he came from.”

Gavin writes about Michael as a man who pushed boundaries, but was also a product of his time. During the eighties, when gay men most often appeared in popular culture as punch lines or punching bags, Michael chose what was sure to be profitable. He wrote about sex as openly in “I Want Your Sex” as Madonna had in “Like a Virgin,” but through the lens of his straight, cultivated image. By 2000, when I began planning a tribute concert of his music, I felt ready to embrace Michael as an elder statesman in the Queer community, even if he wasn’t quite ready for our embrace. As part of my research, I invited Michael to the concert via Shirlie Holliman, a close friend of Michael’s who’d sung backup for him and ran his website. Holliman replied that Michael’s schedule wouldn’t allow him to attend and added, “I am surprised that you are calling George a Queer artist. I can’t think of any reason why someone would consider ‘Queer’ a flattering term.”

As it turned out, the Queers at Oberlin were hungry for a concert celebrating gay lives and exploring how George Michael fit into Queer lineage. The evening of “The George Michael Project,” I stood backstage when the emcee opened the door separating me and the other 45 musicians from the stage. A wall of sound — hoots and hollers of anticipation — hit us all hard. The Queers had come out in droves, some sitting on each others’ shoulders at the back of the venue to hear Michael’s music and celebrate the Queerness of it all. In video footage shot after the concert, many of my Queer peers beam as they speak about how good it felt to hear Michael’s music contextualized through his sexuality, to know that he and they were parts of the same marginalized fabric of society, and how joyous it felt to celebrate his accomplishments as a gay man who’d left an indelible mark on the pop music world. The evening remains one of the best of my life, the energy and joy still in my veins from singing Michael’s Paul McCartney-inspired “Heal the Pain” with my two gay male friends Dave and Vel, or the raucous love we felt after our closing number, “Too Funky.”

I continued to follow Michael, though his fan base had lessened not just from homophobia but due to his age in a field where 30 was often an expiration date. Gavin’s book examines this period of Michael’s artistic exploration, allowing the voices of Michael’s peers and music critics to articulate the richness and maturity of the lyrics on his 2004 album Patience. His period of commercial dominance had ended, but Patience sold four million copies worldwide, a success by any standard other than Michael’s own. Gavin underscores Michael’s vocal skills at the time — while the high notes weren’t as reachable, the emotional depth in his live performances (and on his 2014 album Symphonica) reached new heights.

Amidst these artistic successes, Gavin charts the artist’s descent into drug use with an honesty that Michael probably wouldn’t have wanted, given his ongoing denial about drug use when he was using. When Michael died at age 53 in December 2016, his ex-boyfriend Kenny Goss offered a credible explanation as to what the years of drug use had done to him, “I think his body just gave up. All these years, it was just weak.”

When I began writing and thinking about Michael in 2000, I couldn’t have known how much the world, and our perceptions and treatment of Queer people, would shift over the next two decades. LGBT representation in popular culture still dwelt in tokenism, with Queer people rarely knowing themselves through popular art. Over the course of the decades that followed, not only would we see greater media representation but also more laws that acknowledged and protected us, such as the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015. I wonder if Michael could have even imagined the changes that would come, way back when he started out with Wham!

A Life, while dense, is propelled by the author’s gift for storytelling. While the book may have its greatest appeal to Michael’s existing fans, Gavin illuminates juicy details — like the employ of 90’s supermodels Naomi Campbell and Linda Evangelista in his videos in place of himself, and Michael’s appreciation for and rivalry with other icons like Elton John — that will surely appeal to a wider audience.

***

Gavin initially sets the reader up to believe that George’s father, who was critical of his son’s dreams and skeptical of his talents, is the main reason why one of the great pop music makers of the last century died alone and seemingly insecure. Gavin all but abandons this early thesis and focuses on another, addressing Michael’s alienation as a gay man in painstaking detail in the latter third of the book. The book’s most compelling paragraphs — shared in the epilogue through the words of an unidentified gay man who shared Michael addiction to the drug GHB — feel like a buried lead.

“Is there nothing more horrible than to believe that we’re just not good enough?” the man asks. “That’s the strongest thing that gay men have in common. We constantly believe there’s something wrong with us. Be more masculine… smarter… better looking, better at sports — whatever.”

As the Queer community continues to grapple with our beliefs of “not good enough,” George Michael: A Life stands as a reminder of the inner demons we’re up against, that brought down one of our own. Much like Michael himself, Gavin hooks us with a story millions can relate to. One that begins with a withholding parent, and ends in an intimate and intriguing place that leaves the reader pondering the all too high price Michael paid for believing there was something inherently wrong with him.

Click here to read Jason Prokowiew on why he chooses to capitalize Queer.

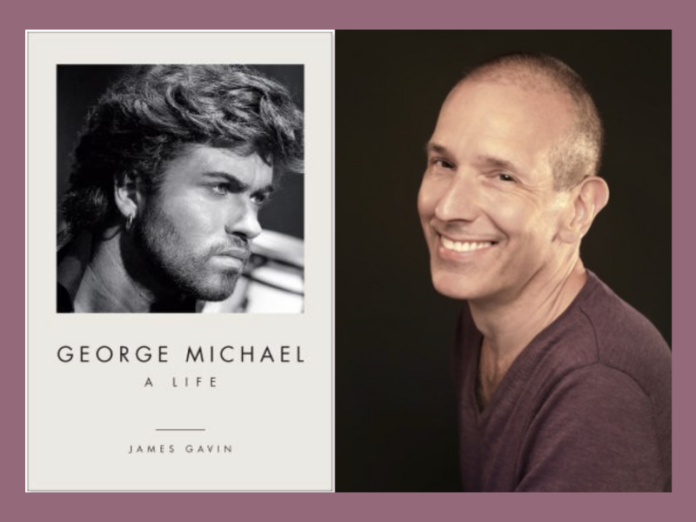

Image: Cover of George Michael: A Life by James Gavin (l); James Gavin, author (r). Licensed under Fair Use Laws.

- George Michael: A Life — A Review - July 29, 2022