ZEITGEIST

On a sunny day in an outdoor cafe in mid-August, I found myself thoroughly absorbed in Oliver Sacks’s memoir, On the Move: A Life, sometimes laughing out loud at the stories it tells, not that Sacks ever strives for hilarity; it’s more that neurology, at least as he practiced and experienced it, can trigger bursts, spasms — Tourettic tics? — of humor.

As I put the book down for a moment, I heard a man at an adjacent table tell his two companions about his history of migraine headaches, and that the best book he had found on the subject was… Migraine by Oliver Sacks. By coincidence, I had just then finished the chapter in his memoir Sacks devotes to migraine, and mentioned it to my neighbors. They were well-versed in Sacks, and eager to talk about him, all the more so because they knew that he was dying. Striking as these coffeehouse coincidences seemed to me, I’m sure they were hardly unique. People online and off were talking about Oliver Sacks.

The migraine sufferer reeled off The Island of the Colorblind and Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain as two of the Sacks books he liked the best, but added that his real favorite was A Leg to Stand On. Another coincidence: though not one of Sacks’s better-known works, it had also been my favorite, and the occasion for the interview with Sacks that I’m republishing here.

In books like Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales, and An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales, Sacks, by bringing neurology to bear on conditions that had been misunderstood or shunted aside, furnished art and literature with new subjects and new kinds of characters. There’s Lionel Essrog, for example, the vibrant Tourettic hero of Jonathan Lethem’s novel, Motherless Brooklyn (1999), and Christopher, the fifteen-year-old autistic boy in Mark Haddon’s novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (2003), which has been adapted into an award-winning Broadway play. It would be very easy to follow these examples up with a host of other stories, novels, studies, and films inspired by the work of Sacks, including, of course, Awakenings, the movie based on his book, in which Robert De Niro plays a patient and Robin Williams a neurologist.

TRUCK STOP

From early on, Sacks kept notebooks of his thoughts and experiences, thousands of them. He was always writing, which necessitates a lot of sitting. Yet movement was essential to him.

The title of his memoir comes from a poem by his friend, the poet Thom Gunn, which “instantly resonated” with him in his youth, when, as he puts it, “Most of all, I loved motorbikes.” Of his time working at UCLA he writes, “By day I would be the genial, white-coated Dr. Oliver Sacks, but at nightfall I would exchange my white coat for my motorbike leathers and, anonymous, wolf-like, slip out of the hospital. . . then race along the moonlit road.”

Midway on one trip back from California to New York City his bike died, and Sacks was picked up by long-distance truckers, staying for a few nights at a truck stop with them. Here’s his diary entry about the truck stop:

Truckers are generally solitary men. Yet occasionally — as in a hot and crowded truckers’ cafe, listening to some infinitely familiar record blaring on the jukebox — they are stirred, transfigured suddenly without words or actions, from an inert crowd to a proud community: each man still anonymous and transient, yet knowing his identity with those around him, all those who came before him, and all those who are figured in the songs and ballads.

At an Alabama truck stop, Sacks finds truckers “stirred, transfigured” — Sacksian truckers. Whether in motorcycle leathers or in a medical white coat, whether observing truckers or Postencephalitic patients under his care who, as recounted in Awakenings, were released from their frozen state to flicker, briefly but intensely, back to life, Sacks was irresistibly drawn to transfigurations. Where others might see only deficit, his genius was to find unexpected enhancements. Where others might detail only the particulars of a handicap, he’d show how brains could compensate, and be reshaped and recalibrated, rather than only reduced.

HANDICAPS

Sacks brought his own set of constraints and compensations to his studies, starting with the fact that he was prosopagnosiac, or in plain English, face-blind. He could not recognize people by faces, as most of us do — quickly and from early-on in one’s life, where being able to pick mom and dad out of a crowd, for example, is a useful trait for any child to possess. But face-blind folk are not helpless with regard to people-recognition; they rely on visual clues — a beard, say, or hairstyle, height, weight, gait — and on assists from other senses. Sacks writes about an encounter with Mae West, who had come to his hospital for a minor procedure, that he didn’t recognize her face, but “recognized her voice — how could one not?”

And he suffered migraines, which presented him with a question at an early age that went beyond face-recognition, namely, “How did we recognize anything?” During a migraine: “My vision could be unmade, deconstructed, frighteningly but fascinatingly, in front of me, and then be remade, reconstructed, all in the space of a few minutes.”

Migraine helped drive Sacks to the study of neurology for answers. Migraine became the subject of his first book, though in it he maintains a clinical distance from personal experience. A Leg to Stand On collapses the distance, which is why it was his hardest book to write, took years, and went through so many drafts.

The tale starts with Sacks on holiday in Norway, blithely contemplating a hike up a mountain trail. At the base of the trail he noted a sign saying: “Beware of the Bull,” which included a cartoon “of a man being tossed by a bull.” This “must be the Norwegian sense of humor” he reasoned. “How could you keep a bull on a mountain?”

The Norwegians weren’t kidding. There was in fact a big white bull residing atop that Norwegian cliff. At first, it seemed placid and beautiful, but transfiguration works both ways. Remember that scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where the beatific angels swirling out of the opened Ark turn into angels of death? That’s how it was for Sacks and the bull, as the bull became “hideous — hideous beyond belief, hideous in strength, malevolence and cunning. It seemed now to be stamped with the infernal in every feature. It became, first a monster, and now the Devil.” Panicked, sure the bull was right behind him — “I heard heavy, thudding footsteps and heavy breathing behind me” — he plunged down a slippery path and wound up with his left leg “twisted grotesquely underneath me and in my knee such pain as I had never, ever known.” He managed to splint his leg with an umbrella he’d luckily brought along, righted himself, and soldiered slowly on, until he couldn’t, as it began to get cold and dark and it was all he could do to remain conscious. Then, suddenly, he heard a “long yodeling call,” and was discovered by “reindeer hunters, father and son, who had pitched camp nearby.” Before long, villagers arrived to carry him to town on a litter.

All that transpires in the first pages of the book. The real adventure is about to begin. Sacks gets the right medical care and the leg mends, except for the maddening detail that it bears no relation to him; he’s convinced it’s not his leg. No matter what the doctors and nurses tell him, or his eyes report, he remains positive: “I had lost my leg.” Oh, he’s read about, even treated such cases, and has ample medical vocabulary for them — somatophrenia phantastica, Pötzl syndrome, scotoma, scotoma for the leg. But now that he is such a case — a patient rather than the sympathetic, learned neurologist he is accustomed to being — such terminology does not suffice, does not keep him from returning in his dreams again and again to his “non-leg.” He turns to John Donne and the Psalms for relevant literature. He listens, endlessly, to Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, a piece of music he had previously considered “trifling” but now gives him the sense of “quickening” he craved. And he thinks about Lurianic Kabbalah.

Lurianic Kabbalah was promulgated by Rabbi Isaac Luria when he settled in Safed (in what’s now Israel) after the 1492 Expulsion of the Jews from Spain, where Jews had lived in fairly consistent harmony with Christian and Islamic culture for centuries. For Luria, the Expulsion was a cosmic explosion, a catastrophe not just for Jews but for God, who was splintered, shattered, wounded and badly in need of re-integration.

Like Sacks.

Tempted at first by the idea, Sacks finally rejected giving A Leg to Stand On a Kabbalistic armature, and kept seeking a form that would allow him to portray his “own intimate feelings in a way which more ‘doctorly’ writings had never done.” The result is what he dubbed a “neurological novel.” Imprecise if not indefinable as that term might be, there is no doubt that the book adheres to the arc of much great narrative — innocence and ignorance; descent, pain, unraveling, decomposition; and finally, recomposition and return.

In other words, the hero’s journey.

TERRORS

Given his genial persona— bubbly, compassionate, explanatory, consoling —it’s easy to underestimate how terrified Sacks could be, and the role of terror in his life, and not only in face of a white bull on a mountain. His older brother Michael was violently psychotic. “Terrified, and deeply embarrassed — how could we invite friends, relatives, colleagues, anyone, to the house with Michael raving and rampaging upstairs,” Sacks had to leave London to escape Michael. “I felt a passionate sympathy for him, I half-knew what he was going through, but I had to keep a distance also, create my own world of science so that I would not be swept into the chaos, the madness, the seduction, of his.”

Sacks has described himself as feeling “very distracted much of the time, darting from one thing to another.” In fact, only terrifying extremes seemed to settle him down, concentrate his fractured attention. He often took his motorcycle to 100 mph. He was a regular at Muscle Beach in California, where he set a record for squats (rising up from a crouch with weight on your shoulders), setting a Muscle Beach record of 600 pounds. (That, he writes, is why Mae West invited him to her Malibu mansion though he didn’t at first recognize her; she liked having young musclemen around.) He took life-threatening amounts of amphetamine.

He quit the amphetamines only when he knew he would write a book, Migraine, which he did, and from then on devote himself to an “oeuvre.”

OEUVRE

Sacks never propagandized for neurology as opposed to psychology, and, significantly, never polemicized against Freud. It was simply not his style, as it was Freud’s, to polemicize for and defend an overarching, ever-expanding theoretical superstructure, a master narrative. Sacks, in fact, admired Freud immensely, for years kept a copy of The Interpretation of Dreams with him, and was in psychoanalysis for decades — although, as he remarks in On The Move, there were times when he failed to recognize the therapist he had been seeing twice weekly for years. “This failure to recognize him came up as a topic . . . I think that he did not entirely believe me when I maintained that it had a neurological basis rather than a psychiatric one.”

Though Sacks recounts it casually, off-handedly, the incident is telling. No one more than Sacks has disrupted what Auden termed the “whole climate of opinion” that had collected, if not coagulated, around Freud.

Freud fixated on the “unrememberable and unforgettable” events of childhood, which for him were the mysteries at the roots of our being. (That they were “unrememberable and unforgettable” gave him enviable license for defining and redefining them as he saw fit). Sacks, on the other hand, proposed–to his therapist, and by means of his writings to the culture at large–that if we have a genuine appetite for mystery, we might do well to think about those of the brain.

Sacks’s friend Stephen Jay Gould put it well about the Freud v. Sacks dichotomy, taking note of the fact that Sacks had in his youth been an avid motorcyclist and an always-keen naturalist. For Sacks’s sixty-fourth birthday Gould wrote:

This man, who’s in love with a cycad

But once could have starred in a bike ad

King of multidiversity

Hip! Happy birth-i-day

You exceed what old Freud, past head psych, had.

The Freudian climate has dissipated. If there’s anything comparable today, Sacks is near its center, with Sacks, not Freud, the master-narrator. You might say, oh, well, the study of mind goes through fashions and has its seasons. But you also might recognize that there is such a thing as progress.

LOSS

Sacks is gone. When the news came that he had died on August 30 of the terminal cancer he learned he had in February, I felt it personally, as did I’m sure many others, including my friends at the outdoor coffeehouse. To quote another friend: we woke to “a sad morning without Dr. Sacks.” But I wouldn’t be completely honest if I didn’t add that along with the sadness I felt a twinge of envy as I read through On The Move. What a life: what an utterly amazing — amazingly expressed, amazingly useful — life this Oliver Sacks lived.

INTERVIEW

[In 1995, Harvey Blume interviewed Oliver Sacks for an article in the Boston Book Review, “The Casebook of Oliver Sacks,” where Sacks discussed in detail his books, his career, his devotion to neurology, and a wide range of other topics. We republish it here.]

“We are in strange waters here, where all the usual considerations may be reversed — where illness may be wellness, and normality illness, where excitement may be either bondage or release…It is the very realm of Cupid and Dionysus.”

from The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Oliver Sacks: People ask, are you still a doctor, do you still see patients, or are you just a writer? As you just saw for yourself [a man in a wheelchair had just left the hotel room where we talked] I see patients. It is my life and I never want to stop.

Harvey Blume: In A Leg to Stand On, you write, “If my attention is engaged, I cannot disengage it…It makes me an investigator. It makes me an obsessional. It makes me, in this case, an explorer of the abyss…” Do you have a neurological disorder that compels you to examine neurological disorders?

OS: I feel very distracted much of the time, darting from one thing to another but I think there is some sort of consistency or tenacity to it.

HB: And in An Anthropologist on Mars you describe yourself as a physician called “to make house calls, house calls at the far borders of human experience.” That would seem to apply to all your work.

OS: This man in the wheelchair was a house call. It was exactly what my father would have done when I was a kid. I used to love to go with my father on house calls. He was often called a whiz at diagnosis. It got around and if he went to Edinburgh or Lisbon someone would know and phone him up. He would see them in his hotel room.

HB: So you carry on the tradition. But I hope you won’t be offended if I say that your work brings to mind P.T. Barnum and the age old fascination with borderline human experiences.

OS: I think it does, although I’m obviously vulnerable and sensitive to the notion of Sacks’s freak show. Museums started partly as cabinets of curiosities — wonders, marvels, and prodigies.

HB: The boundary conditions of being human have always been of interest.

OS: For me it’s a way of looking at being human rather than being inhuman.

When I was young my mother, who was a surgeon, used to take me to the Royal College of Surgeons Museum. That was Hunter’s original 18th century museum. It still had a skeleton of the Irish giant, the Sicilian dwarf and the skulls of Turgenev and Anatole France next to each other. And my father would tell me, when he had been a young man at the London hospital the Elephant Man was still a memory for many people. So if you want, looking for prodigiousness is in me but always to illustrate the extent of humanity, of human capacity and diversity.

I was very moved some years ago in a Mennonite village in northern Canada where a fifth of the population has Tourette’s. I was wondering how this deeply religious community would deal with it. Basically, their attitude was similar to that expressed in an old Jewish blessing to be said on seeing a strange person: you praise God for the diversity of Creation.

HB: In A Leg to Stand On, which is about your own accident and recovery, you describe turning to the Psalms at a certain point; you describe the Psalms as case histories. This applies, in reverse, to your own work. You turn your case histories into psalms; you look for the redemptive value in people’s experience of suffering and anomaly.

OS: Somewhere I quote Nietzsche from the preface to The Gay Science where he says suffering doesn’t make us better but it may make us more profound; it makes us descend into our depths; it makes one question more severely than one has questioned before. I am certainly very conscious of this deepening and pensive quality, this reflective quality in many patients. There are also those who are destroyed — devastated, embittered, maddened. But there are those who are strengthened, who discover other resources, and who are transformed in some sort of way, physiologically and neurologically. But I certainly would not, as it were, prescribe an affliction for its redemptive power.

HB: Though in A Leg to Stand On there is a sense in which you feel privileged to have undergone that journey.

OS: I think I did, and this is partly what A.R. Luria [a Russian neurologist] said to me when I wrote to him — and he is, in a way, my mentor, both spiritual and neurological. He said, I’m sorry this happened to you but since it did, since you have this power of introspection and articulation, describe it from the inside as it’s never been described before. That is what I tried to do. But some of the other patients in hospital said to me, you lucky bugger, we’re suffering and you’re turning it into a book.

HB: A Leg to Stand On is a story of descent, a literal descent down a hill and a descent into the self. You look into the face of a bull near the top of the hill. The bull doesn’t do anything; he doesn’t chase you.

OS: No, no he was probably sitting there placidly.

HB: And all of a sudden you see the devil. You flee and severely injure yourself.

OS: I found that the most difficult of all books, partly because every time I worked on it I would be thrown back into an unbearable reliving of the situation.

HB: One minute it’s The Sound of Music — there you are, striding confidently uphill — and then it’s suddenly The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari where everything is dark, grotesque, disassociated, fragmentary.

OS: I was haunted by this experience. I was in danger of having it again if I couldn’t get it out.

I suggest half-facetiously that the book should be read under spinal anesthesia so the reader will know in himself what I’m talking about. These things are really quite unimaginable. When you have it, you cannot imagine it otherwise, and when it’s not there you can’t imagine it. The absolute unimaginability of all sorts of terrible neural knowledge which comes and goes is what I’m talking about.

A very Parkinsonian patient of mine managed, before he froze up, to inject himself with medication. A minute later he straightened and said, “I have forgotten how to be Parkinsonian.” Then he added, “In forty or fifty minutes, when it wears off, the terrible knowledge of how to be Parkinsonian will come back.”

HB: A Leg to Stand On is a portrayal of a nightmare, a story of being lost in one’s alienation.

OS: This particular sort of nightmare, alienation from one’s limbs, is extremely difficult, first of all, for the person to communicate to the doctor. But if a communication can be made, it is then very difficult for the doctor to communicate it further.

William Mitchell, the first to describe phantom limbs, originally used a fictional form. But the negative phantom — the absence, the alienation — has never made its way very well into the medical literature.

HB: Though it’s the kind of thing 20th century literature is so good at portraying.

OS:: And it existed under Hippocrates.

HB: You describe A Leg to Stand On as a neurological novel. In what sense is it a novel?

OS: I don’t know. Actually, I’m not a novel reader or writer and I’m no good at plot design and character; I’m a chronicler. Genre is not a word I use a lot. I don’t know what is meant by deconstruction. I’m ignorant of literary theory and indifferent to it. I don’t think of myself as a writer or an artist. Well, I do and I don’t.

HB: In Awakenings you prescribe art as a remedy for your patients. Art seems central to your work.

OS: At all sorts of levels, including the level of the man I just saw, who often can’t walk but he can dance. Certainly the case history itself has to be almost equally art and science.

I don’t know who my models are. Like many people of my generation, I adored the H. G. Wells’ short stories and was also very fond of Chesterton. I footnote Wells’ “Country of the Blind,” though strangely that footnote has only become relevant in an experience I’ve had subsequently, when, last summer, I went to an island of the colorblind and saw a whole community who for two centuries have had no perception and no conception of color. They’ve organized their lives in completely different terms and regard us so-called color normals as distracted by chromatic hallucinations.

My tastes are rather conventional. I was brought up with Dickens and Trollope. My mother used to read D.H. Lawrence stories to me when I was young. I just came across a marvelous poem of D.H. Lawrence in which he speaks of how red is essentially sensuous and how “even God can’t think of red.”

Writers who may have been a model for me — I still love reading them — are the naturalists. I love Humboldt’s personal narratives, Darwin on the Beagle, Wallace in Malaya, the notion of the scientific adventure. For that matter, I’m fond of Conan Doyle, not only Sherlock Holmes but the Challenger books, especially The Lost World. I used to know it by heart.

HB: You talk about Sherlock Holmes as possibly an autistic personality. It’s also tempting to think of you as a Sherlock Holmes type setting out to unravel mysteries.

OS: It’s not clear that Holmes’ cases form an oeuvre, that there’s a movement, that they’re connected one with the other, that he becomes wiser, that he develops in any way. And I hope for something like that. I do feel called to a case here and a case there and I like being on the case but I do hope at a deeper level, which Holmes doesn’t have, there’s something happening.

HB: Doyle sends Holmes off to demystify the world, to solve all mysteries and leave none intact. And then, of course, Doyle himself becomes a spiritualist.

OS: I’m very much, myself, for mystery. I’m very much against mysticism. I feel for example that Stephen Wiltshire, in An Anthropologist on Mars, is quite mysterious; I don’t know what goes on in him. I don’t know that I mean mysterious like the Trinity, which is merely incomprehensible. I don’t understand mystery in that sense. But it may be mysterious like late Beethoven.

HB: Dreams play a crucial role in so much of your work.

OS: I have published a paper called “Neurological Dreams” which examines the level at which neurological events enter dreams. For example, I describe such a dream in A Leg to Stand On where there’s an annihilation bomb that is a migraine entering the dream. I also approached this in “The Last Hippie.” Physiologically, one sees there’s less and less difference, in some ways, between the waking and the dreaming state, and there’s the notion that waking is, in fact, dreaming in the world; it’s dreaming within the constraints of external perception. So I do think of dreaming as almost the most fundamental mode of being a human being. I have sometimes said that I think of Tourette’s as form of public dreaming, in which outer events and inner events join in manifest dreaming, visible and audible.

I don’t believe in prognostication in any deep sense, although I think that work may be done in dreams which may alter reality. I give an example of that in A Leg to Stand On when I was asked to put down a crutch and walk. I tried and fell over. Then I had a dream in which I threw the crutch away. I woke up and immediately did so; it had been rehearsed in the dream. Why or how Magda, in Awakenings, dreamed she was going to die the day she did, I don’t know.

I go along with Freud about the occult; I’m very fond of mystery; I hate the occult.

HB: You have a romantic notion that the distinction between illness and health is blurred, and that illness can be not a deficit but an enhancement, as in Thomas Mann’s Dr. Faustus.

OS: Indeed, I quote it at length in the “Leg” book.

HB: In The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat you wrote, “What a paradox, what a cruelty…that inner life and imagination may lie dull and dormant, unless released, awakened, by an intoxication or disease!”

OS: Yes, that was about Natasha, who said I feel so well I must be ill.

And I think of that last novella of Thomas Mann, The Black Swan, where a post-menopausal woman at a spa feeling fortyish and sad meets a young man who’s very attentive. She falls in love and starts to feel marvelous. Then, strangely, she bleeds again. Perhaps her periods are coming back, her youth returning. Everyone compliments her. Then she starts to feel ill and gets a bad color and has a huge hemorrhage. In the last scene, she is on the operating table. The surgeons are talking. She has a secreting tumor in her ovary, which has metastasized everywhere. One of them says, something like this would produce a great surge of estrogen, of hormones, and might produce an aphrodisiac state. Another says, perhaps it’s the other way around; perhaps falling in love can cause the ovarian tumor.

Certainly with something like Tourette’s, whatever the suffering and disability, there may also be energy and spontaneity. I was just in Toronto seeing a friend of mine, a very Tourettic artist. Sometimes the Tourette’s can tear him apart; it can be full of a pantomimic impulse. Other times it can all rush together in the form of creativity. He doesn’t want medication because he fears it will take the edge off, although when I see how terrifying it is I fear for him.

People have called me on romanticizing illness and there may be some truth to it; I’m prepared to retract that somewhat. But what interests me, especially now, is that new health is to be achieved through reorganizing. So that in the case of the colorblind artist, he first of all finds himself in an impoverished, ugly, abnormal world drained of meaning and feeling because color had been such a vehicle for him. At that point he is suicidal; he feels it’s the end of him and his art. Then, the change occurs. What had been hideous and ugly and impoverished becomes fascinating, privileged and beautiful.

HB: So the implication may be not, say, that Beethoven only coped well with silence but perhaps that he learned from silence, heard something new in it.

OS: Perhaps became a different sort of composer. I thought of this most deeply in regard to the colorblind artist, who clearly went through a descent and a redemption but the redemption was to a different form of being, into a quite different life of art and the imagination. It’s one of the clearest examples for me of loss in one way, and redemption through reorganization.

HB: At the end of the piece on Stephen Wiltshire in An Anthropologist on Mars, you ask, “Was not art, quintessentially, an expression of a personal vision, a self? Could one be an artist without having a ‘self’?” Are you prepared to answer that question?

OS: No. That’s why I left it as a question. The whole book is full of questions. I’m an inquirer more than an answerer.

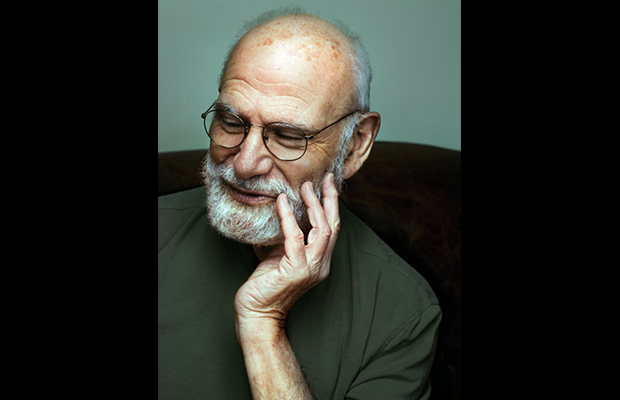

Photo: Oliver Sacks by Maria Popova; licensed under CC BY 3.0

- The Fatwa on Chess - January 31, 2016

- Oliver Sacks: A Hero’s Journey - October 5, 2015

- Allen Ginsberg:An Encounter - November 24, 2014